Amina was 17 when a Boko Haram terror member pointed a gun at her mother, hoisted her atop his bike, and made away with her. It would be another eight years before she would see her mother again. She would be 25, with three kids of her own. She would have been married off to three different members of the terror group at different times, and she would have become partly radicalised by the experience.

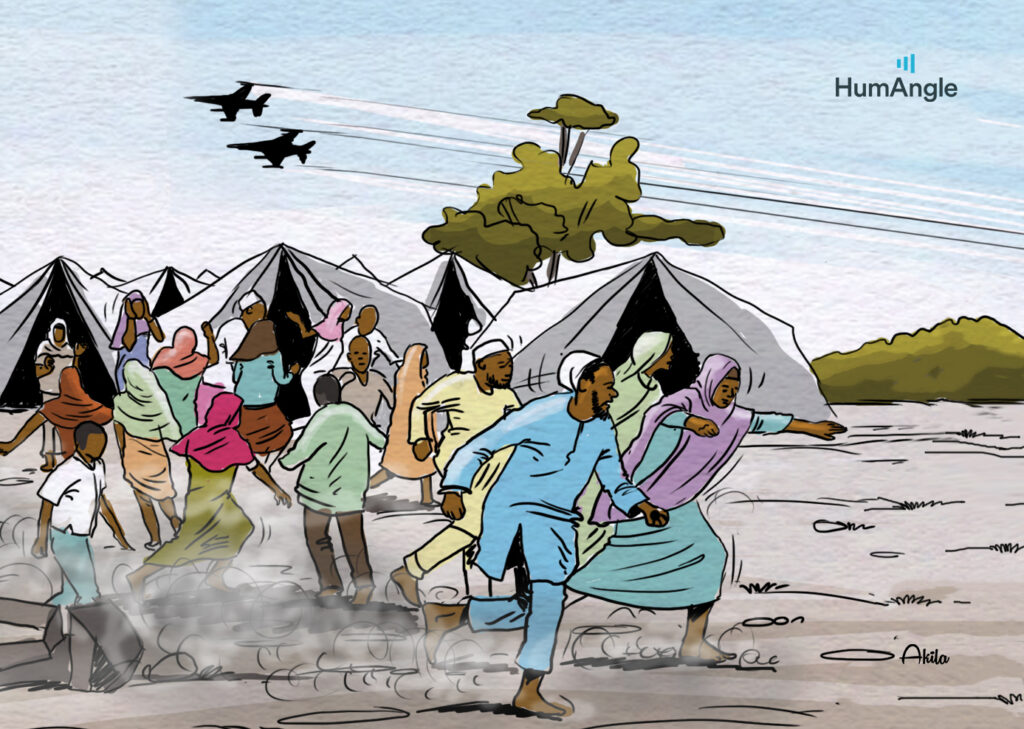

When the insurgency started, and attacks were going on in Borno, northeastern Nigeria, Amina’s mother, who was resident in the rural part of the state, became terrified by it, like many other people. However, she did not feel unsafe enough to flee until the military, while trying to apprehend members of the terror group, began to harass civilians. The year was 2014, and displaced people fleeing the insurgency were being arrested in their hundreds on accusations of having affiliations with Boko Haram.

Amina’s mother was living in Bama at the time, widowed and with a daughter to keep safe. So she fled.

“My mum left Bama to Chad because, at that time, the military was harassing people … They arrested people indiscriminately and set fire to houses and buildings. We had to run away. We went to Chad.”

It was to be the site of her abduction.

“That was when Boko Haram kidnapped me. They pointed a gun at my mother and took me.”

Life in the caliphate

Once at the Sambisa settlement, Amina was put into one of the tents with other girls her age, who were newly brought in or had not been married off yet. There were several tents like that. Usually, she said, the waiting period in the tents was only a couple of weeks before they would be married off, but they spent an unusually long time there.

During this time, some girls, as young as seven years old, were being sexually abused by some group members. One of them, who says she had been seven at the time, told this reporter that the sexual violence was so bad that she could not walk properly due to the pain between her thighs. As a result, she would crawl to the food or limp whenever the guards inspected them and gave them food. On some days, she just sat down and forfeited the food because she did not have the will to walk. Then one day, one of the guards asked what was wrong with her that made walking so difficult, asking if she fancied herself above the food they offered.

“I did not know whether to tell him the truth because the two men raping me told me that they would kill me if I reported them,” she remembers.

But the man questioning her already seemed angry enough to harm her if she did not provide a convincing answer. So she told him the truth: two men had been abusing her and a few others of the captives at nights when everyone else had slept off. She was asked to identify the men. She did, and they were then taken away. She never saw them again. Much later, she learned that the group executed them.

Not long after this, Amina was married off to the man who abducted her, even though she was only a teenager.

Married to a terrorist

Despite the circumstances of their meeting, Amina’s experience being her captor’s wife was not as bad as she feared it would be or as bad as many other people’s, she says.

“The man did not treat me badly. We spent one year together and even had a son.”

Her day usually started with her making breakfast for her husband and baby. When they were constantly under attack by the Nigerian army, however, they were always on the run and rarely got any sleep.

“Back in the forest, we didn’t sleep well. We went out after morning prayers and came back after evening prayers. That time, bombs were being dropped regularly. There was a time it dropped in front of my house.”

But on normal days, after breakfast, she went to the Islamic school known locally as Islamiya. There, she would listen to sermons about how treacherous it was for members of Boko Haram to return to Nigeria and live because Nigeria was an infidel country. Their husbands also warned them against running away, especially with their children.

“They say if we die there, we will enter paradise. But if we die in Nigeria, practising what the country is doing, we will go to hell. They say if you run away and take their children to an infidel country [Nigeria], they will never forgive you, and they will find you and kill you,” sense of vengeance is as violent as their ideologies. HumAngle spoke to one woman who admitted that she had left three of her children behind and only left with her baby, whom she was still nursing.

“I am always thinking about my children I left in the forest; I have sleepless nights crying because of them. People normally say I have slimmed down. It’s because hunger and the thoughts of my children won’t let me gain weight. I am always praying to God to let me see them again someday,” she agonised.

Amina’s first marriage in the settlement was peaceful until it ended when her husband died by execution at the hands of the terror group.

“He married a young girl without seeking their permission. So they found out and killed him as punishment.”

HumAngle understands from interviews with several women that the men were mostly executed or punished for issues surrounding weddings or unions that were not appropriately done and rarely for marital feuds. For example, the concept of rape was only taken seriously and punished by death where the man is not married to the woman. In instances of marriage, rape is not recognised, just as in Nigerian laws. Further, if a man married a woman forcefully without paying her dowry, the marriage would be annulled. When he simply took her into his house as his wife without marrying her with permission from the group, like Amina’s husband, he was to be executed.

While the group insisted on not forcefully marrying women off, women who rejected the marriage offers were secluded and sometimes turned into slaves for high-ranking members of the group, Amina says. They were also kept in much worse conditions than other women. For example, Amina says that most of the Chibok girls abducted in 2014 who refused to be married off were kept in these conditions. They were secluded and not allowed to mingle with other captives. Though some of them have been released as a result of negotiations with the government, with others escaping, others are still in captivity.

“The Chibok girls were kept in a different part; they never let us mingle with them. Though sometimes, in times of battles when our husbands would be away for a long time, we got to mingle with them and hear their stories,” Amina explains.

Visiting neighbours were often frowned upon by the men, who claimed that the women were gossiping or plotting to escape. To circumvent this, Amina says whenever her husband came home when she had a friend who was visiting, they quickly raised their voices a notch higher and started to talk about religious matters or sometimes reciting verses from the Qur’an.

Remarrying in the caliphate

Because of the swiftness of the death penalty being used amongst the men and the fact that they were constantly under attack by the Nigerian army, foot soldiers usually did not last long. They died frequently. As a result, a woman could be married off two to three times during her stay among the group.

After she completed her mourning period following her first husband’s execution, she was married off to another person who she says treated her monstrously. She says he left her starving many times, beat her up, and sometimes threw away her belongings, asking her to leave his tent.

On one such occasion, she had to stay with other people. Yet he would not divorce her.

“He was just making me suffer. And the hunger! Don’t get me started on the hunger. Sometimes when he feels like it, he would bring grains home for food; sometimes, he won’t. My neighbours were the ones who sometimes fed me.”

She also talks about the sex and how aggressive it was. “The only time he let me be was when I was on my period,” she says.

Later, she found she could not continue, so she tried to escape.

“I got tired and decided that even if it cost me my life, I would leave.”

She did not make it far before being caught and brought back because she had travelled within territory owned by the terror group. She was locked up in prison when she returned to the settlement.

The prison was mostly made of zinc, with no concrete nor any significant source of ventilation. As a result, inmates were usually packed in a tiny space and left without food, leading them to starve, sometimes to death.

“There was a particular woman whose husband reported her for some reason and they put her in prison. She was even pregnant. She died. She died with her baby inside her. Like that.”

Amina was in this prison for 15 days. She says she almost died.

“It was very hot. No food, no water, many times.”

She says that the same justice system was not always applicable to men. Sometimes, when women reported their husbands, they were blamed and sometimes punished for doing so. Marital issues were never really addressed.

“I have never reported my husband. Some women do, but they don’t get justice.

“There was a man that beat his pregnant wife to death. He beat her until she died. They didn’t do anything to him. He even got married to someone else after,” Amina recalls.

When she was released, her husband said he could not take her back after doing something as treacherous as trying to leave the group.

“He said because I wanted to run away, he could not take me back, so he divorced me.”

She observed the mandatory waiting period after divorce and was then married to another man.

Escape

Having tried to escape before and failed, she knew that her next escape would have to be better plotted and successful, no matter what. She had been lucky enough to be imprisoned for 15 days when she attempted to escape. Unfortunately, many people were usually slaughtered when caught. This time, therefore, she banded with other people. She was successful. She made it back home and traced her family.

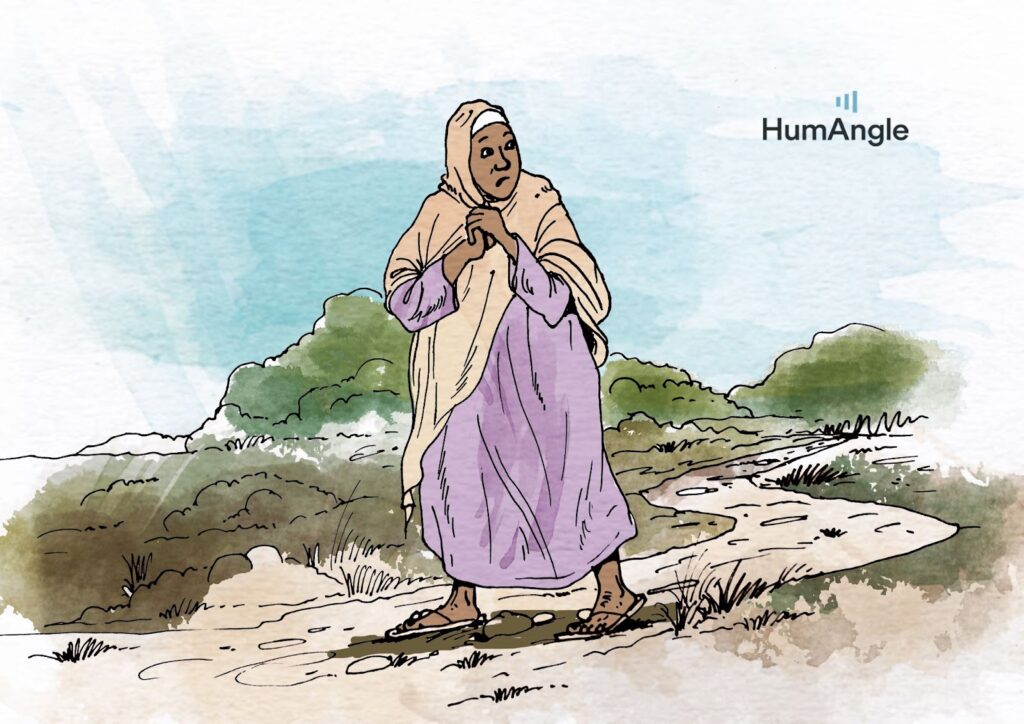

When her mother saw her, she wept.

“She said I had lost all my hair.”

Amina says life as a family still displaced is difficult.

“My mother looks devastated. She looks terrible. But we thank God since we are alive. Still, there is no food or any form of relief materials.”

This report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter