Lawless Sky: The Cost Of Nigeria’s Accidental Airstrikes

Nigeria’s security forces continue to shell civilian settlements in air raids targeting terror groups. Experts are concerned lessons are not being learnt from the mistakes.

Badamasi Alma stood in the middle of the rubble with tears in his eyes and his teeth clenched as he looked at his wife, Aisha, drenched in the pool of her blood, gasping for breath. Her voice was slowly growing weaker before it finally fell to a drop. The military had just dropped a bomb on his village, Ido Ruwa, in Nigeria’s northwestern state of Zamfara, in an air raid targeting terrorists.

It’s the morning of the Muslim Eid el Fitr celebration in early April. Badamasi sat outside a relative’s residence with his four-year-old son, Anas, sorting meat for his family to celebrate the festival, which marked the end of the Ramadan fast. He arranged the slabs of meat into five portions and handed a bowl to Anas to give to his grandfather. He had only just resumed rinsing the remaining pieces when he saw the aircraft whirring over the village. Badamasi stood up to get a clearer view, just like some of his neighbours.

“l saw the aircraft from the East and stood up to see where it was heading. As it flew over my place, I heard a loud explosion from the sky,” Badamasi, 36, began in a low voice that reeked of emptiness and loss.

He took some steps away from the explosion and lay flat in a bush nearby when he heard another deafening sound. A sudden rush of dust enveloped the area. He could barely see. Immediately he realised that the coast was clear, Badamasi raced towards his house. He met his father and brother, both covered in dust, on the way too and hopped on their motorbike. By the time they got there, he saw his whole life crushed before him like a pack of bricks. His three wives and six children were under the ruins of the building.

“It was only Aisha that we met alive, but she could barely speak. Her limbs were gruesomely severed; only one of her hands remained intact,” he recalled, as he heaved a long sigh before pausing briefly to catch his breath. “Where is…?’ she called for me. I quickly responded, ‘I’m here.’ Her eyes met mine as she whispered, ‘Please forgive me, for the sake of Allah.’ Without hesitation, I replied, ‘I have forgiven you.’ She then asked for her father.”

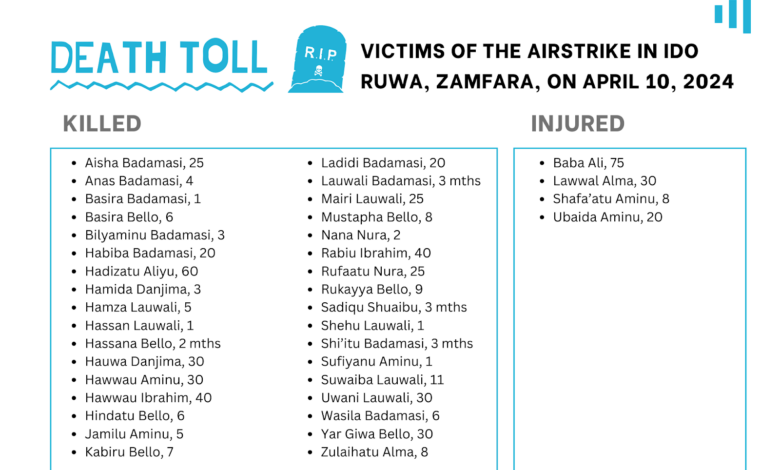

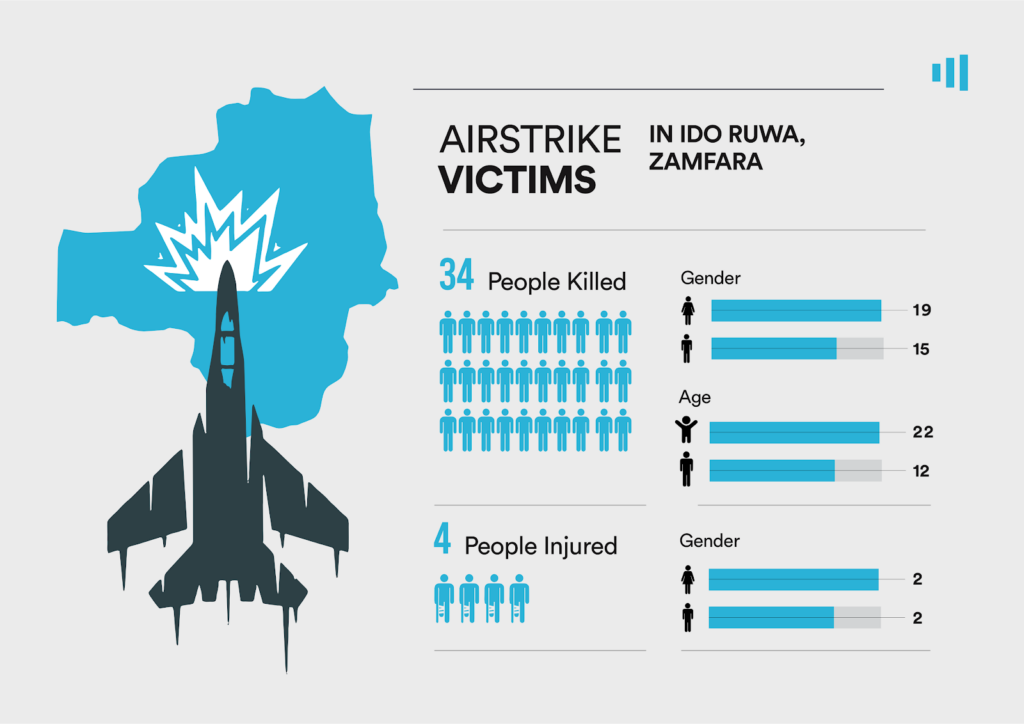

“I couldn’t bear to watch her in pain,” he said. It was not long after Badamasi stepped away from the scene that she gave up the ghost, too. That day, Aisha and thirty-three other people, mostly children, lost their lives to the airstrike.

“All of them were buried in two big graves because the body parts were scattered everywhere. They were picked one by one. Some of the bodies were so badly damaged that we could barely recognise them.”

Later the following day, the Nigerian Air Force announced that it had eliminated terrorists in several locations in Zamfara, including the Maradun area of the state where the village is located.

Armed gangs, locally known as bandits, have subjected people in the country’s North West to a reign of terror for close to a decade now as authorities struggle to contain the growing violence. They sack villages, sexually assault women, impose levies on communities, kill locals, and control a million-dollar kidnap-for-ransom enterprise to keep their operations running.

There are believed to be as many as 30,000 terrorists belonging to different camps in the region. They wield considerable influence in some rural areas, acting as the de facto authority. Locals live under their harsh laws in such places. They also go as far as imposing levies and forcing able-bodied men among the communities to work on their farms.

Since 2011, when the crisis escalated, over 20,000 lives have been lost to armed violence in the North West, according to data gathered by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) Project. The crisis has also displaced over 600,000 people across Kaduna, Kebbi, Sokoto, Katsina, and Zamfara.

Authorities have launched offensives into their hideouts in the forests and rolled out some measures, including designating them as terrorists to allow for stiffer sanctions under the Terrorism Prevention Act.

A deadly pattern

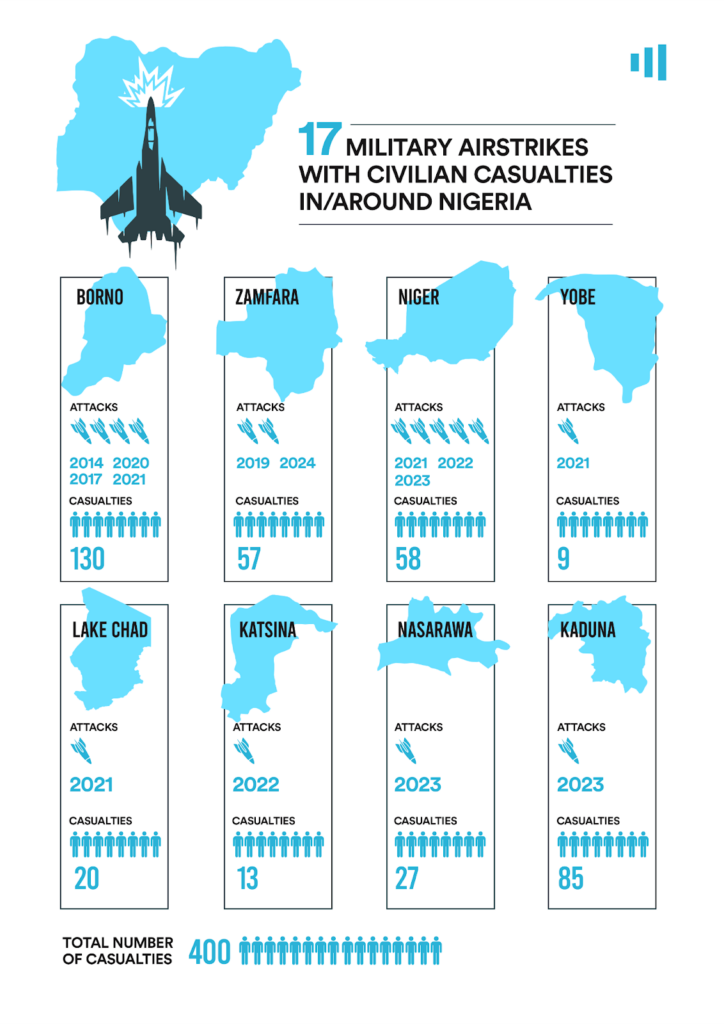

Civilian fatalities from military airstrikes in conflict areas across Nigeria are a recurring problem. The military has bombed displacement camps and civilian settlements while targetting non-state armed groups, which have made the country’s ungoverned spaces their operational base, from which they launch attacks, stockpile weapons, and keep their kidnapped victims.

So far, there have been at least 17 documented incidents of the military bombing civilian communities since February 2014, when a Nigerian military aircraft shelled Daglun, a village in Borno, killing 20 civilians. These recurring incidents have led to the deaths of at least 400 civilians and injured hundreds of others — in clear violation of international humanitarian laws that mandate minimal harm to civilians during conflict.

Military authorities hardly acknowledge these casualties or provide information to support victims, including measures taken to mitigate future mishaps.

In a rather dramatic twist, after a military drone attack that killed 85 locals in Tudun Biri late last year, the army chief apologised and promised to launch an investigation into the incident.

More than four months later, the military said it had concluded the investigation and ordered two of its officers to face court martial proceedings but is silent on support for the victims.

Experts are quick to point out that these incidents have far-reaching consequences.

“It’s worrisome. Consistent military airstrike mistakes are definitely going to project what most people would perceive as persistent military incompetence and at the same time erode the trust of local communities in such counterinsurgency operations, particularly if it has become a recurring issue,” Oluwole Ojewale, an analyst at the Dakar-based Institute for Security Studies, told HumAngle.

Late last year, James Barnett, a specialist in Nigerian politics and security at Hudson Institute, told us following the Tudun Biri incident that the airstrikes show the extent civilians are increasingly getting caught in the crossfire.

“Many people traditionally have not thought of the North West as a war in the same sense as the Boko Haram conflict in the North East. But what we’re seeing is that, in fact, the North West is increasingly militarised, increasingly experiencing violence between powerful non-state actors and the full force of the Nigerian military, and this is going to have repercussions on local communities that are caught in between the two sides.”

Within the last two decades, the U.S. has approved more than $2 billion in security aid and weapons sales to Nigeria. In 2021, Nigeria took delivery of 12 Super Tucano warplanes as part of a $593 million package approved three years earlier. The following April, the U.S. approved nearly $1 billion in arms deals that led to the purchase of 12 AH-1Z attack helicopters and supporting munitions, despite American lawmakers raising concerns about possible human rights violations.

While the boost in firepower has helped to decimate terrorist strongholds, it has also put civilians in Nigeria at greater risk.

“When the people that are supposed to protect us are the ones attacking us, what hope do we now have?” asked Lawali Ango, the village head of Ido Ruwa.

“Bandits attack us, too. Who do we complain to? But saying that they didn’t do what they did to us is a lie. It was a town they burnt down, not a bush and they have seen it. If they are looking for bandits, they know where they are.”

‘I wished for death, too’

One step at a time. The road to recovery is still very bumpy for Badamasi. For weeks after the incident, he would lock himself in a room and pray to God to take his life. When it appeared God was not listening, he would drench himself in tears.

Badamasi now stays with relatives in Gidan Kano, a small settlement in the Maradun area of the state, along with other villagers who have fled their homes following the air raid.

“If not because of the assistance from Islamic scholars who have been writing some Qur’an verses for me to drink, l would have run mad,” he sighed. “Even now, whenever I go to the village, I still cannot believe that it happened.” When he lifted his head, his eyes were filled with the tears he’d been trying to choke back.

Isa Sanusi, country director for Amnesty International in Nigeria, said authorities’ consistent failure to hold the military to account is responsible for the recurring airstrikes that continue to “put people living in rural areas, already beset by conflicts, in greater danger.”

“This is not the first, not the second, and may likely not be the last of such reckless airstrikes that affect people,” Sanusi told HumAngle. “Airstrikes with high numbers of unlawful killings have become the latest in a long list of gross human rights violations perpetrated by the Nigerian military.”

Analysts say the clear disregard for civilian lives during these operations is worrisome.

“That this is coming against the backdrop of the recent investigation into the incident in Tudun Biri and, within the same period, shows that the military has not quite learnt its lesson or done the necessary overhaul to prevent these incidents. So for them, it is more of business as usual,” Confidence McHarry, a security analyst at Lagos-based think tank SBM Intelligence, told HumAngle.

Ojewale believes there’s a need for an overhaul of the counterinsurgency operations in the areas, particularly “in terms of precision targeting, the grading system and other scientific knowledge and activities that are supposed to guide such military air strikes”.

For many affected residents, there’s no home to return to, and they are struggling to get by. The problem of food becomes an acute, daily agony. Sometimes, their relatives feed them, but for someone like Badamasi, who once had a flourishing family and business, it’s a constant reminder of what life had been like for him.

He speaks of compensation for what had been done to them but wants something much more. “We need the people that did this thing to us to know that we’re not bandits (terrorists),” he said. “And since life has been lost, even the houses and foodstuffs were burnt, most of us don’t have anything to do and would like to provide for our remaining families. So if there is anything, we need roofs back over our heads.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter