Land Disputes Tear Adamawa’s Bachama and Tshobo Tribes Apart, Leave Distrust Behind

Two months after a land dispute between the Bachama and Tshobo communities in Lamurde, northeastern Nigeria, that left deaths, displacement, and destruction, calm has returned, but relations remain broken.

After losing his three-bedroom apartment and a store during a crisis in Adamawa, North East Nigeria, Morisson Napwatemi says it may take him a lifetime to recover.

Morisson, a resident of Rigange village in Lamurde Local Government Area, recalls the night on July 6 when it all happened. “I was in my house with my family when we heard people screaming. We came out and realised that neighbouring homes were on fire and people were running around,” he said.

Young men stormed the neighbourhood, hurling burning logs. His house soon caught fire. “My children managed to pull out two mattresses, a mat, and three bags of maize,” Morrison recounted.

He escaped with only the clothes he wore that night. Attempting to save other items, he explained, would have meant risking his life and that of his children since the fire had engulfed his entire house. He stood by and watched the house burn to the ground.

“I lost properties that I can’t even estimate,” he said. “My food items, apart from the three bags of maize we salvaged, my furniture, clothes, seeds that I have saved for planting, and everything were lost that night.”

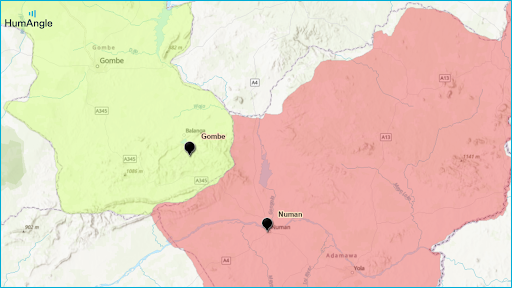

Like many others fleeing Rigange that night, Morisson and his family trekked about a kilometre to Lamurde. There, they boarded a vehicle to Numan, a nearby local government area, to stay with a relative.

The violence raged for over twenty-four hours, leaving three people dead, 53 houses destroyed, and 170 partially damaged homes, while many were displaced, according to local authorities.

But the flames that consumed Rigange and other villages had been lit a day earlier. What started as a quarrel over farmland between Bachama and Tshobo youths quickly spiralled into a full-blown communal conflict.

The disagreement

The Bachama and Tshobo ethnic groups have lived side by side in Lamurde for centuries, sharing schools, markets, water sources, health centres, and even marriages. For generations, both groups had coexisted peacefully.

“If I were ever told that a Tshobo man would clash with a Bachama man, I wouldn’t have ever believed it. We have been living peacefully,” Morisson said.

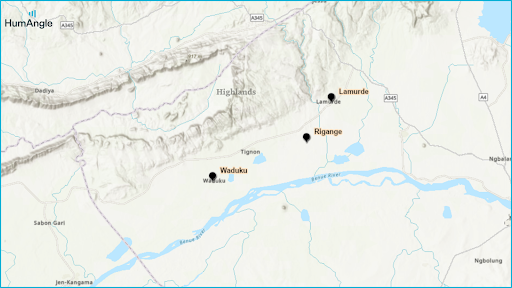

The Tshobo inhabit the mountainous area of Lamurde, including Wammi, Lakan, and Sikori, which extend towards the border with Gombe State. The Bachama, on the other hand, are settled in Rigange, Waduku, and other lowland areas. In Waduku and Lamurde towns, both groups live side by side, often speaking each other’s languages.

Barely a kilometre apart, they fall under the same local government council, with most of the shared social infrastructure located at Lamurde town, the local government secretariat. That is why the quarrel on July 5 came as such a shock.

Locals told HumAngle that the dispute over farmland in Waduku, with both sides claiming ancestral ownership, quickly escalated after mediation efforts failed. By the next day, kinsmen were setting each other’s communities ablaze.

Waduku, Rigange, Wammi, Lakan, and Sikori were struck the most in the attacks.

Walls were torn, homes were burnt, valuables like motorcycles were set ablaze, and animals were slaughtered and left to bleed in the compounds where they were found.

While the Bachama people moved into Lamurde town and Numan for safety, the Tshobo community sought refuge in the mountains bordering Gombe. Among those who made the climb was Joy Wilson, a 52-year-old health worker from Wammi.

“That night, our men told the women and children to climb the mountains very quickly because Bachama youths were approaching our village,” she recalled. “We were still trying to get there when we spotted a village near us, called Lakan, burning. I ran with the other women and got to the mountain top.”

From there, she saw a mob with sticks, guns, and burning logs approaching her village.

“They were shooting guns and burning places. Our men didn’t follow us to the mountain. They went back to the village to defend it,” she said.

Joy had taken her phone to the mountain and stayed in touch with her father and brothers all through that night and the day after. They told her that the doors and windows to her family home had been destroyed, three goats slaughtered, two motorcycles burnt, and their dog was missing.

“The following day, my brother said the entire house was burnt to the ground. Nothing was saved. Absolutely nothing. They also burnt our farm equipment and one bag of rice we had saved as seed for planting, ” she said.

When the violence subsided, Joy and the women and children remained in the mountains for another day, fearing the clashes might erupt again. After enduring 48 hours of hunger and cold, they finally returned to the village. With her home reduced to ashes, Joy and her family moved in with their extended relatives.

“To date, I don’t know the exact story behind the attack. All I remember is fleeing with others because people attacked our community and wanted to kill us,” she said.

Residents told HumAngle that on the night of the crisis, Tshobo youths attacked Bachama-dominated villages around Rigange and Waduku and burnt houses. Bachama youths also razed homes in Tshobo settlements in retaliation.

Security forces were deployed a day later, and the Adamawa State Governor, Ahmadu Fintiri, imposed a 24-hour curfew on Lamurde LGA. He promised safety for all residents, but the attacks continued.

Bodies on the riverbank

On July 15, four young farmers from Wammi village went missing after heading to their fields to spray pesticides. Two days later, their bodies were found on a riverbank in nearby Lau, a local government area in Taraba State, hacked with machetes.

Two of the deceased were nephews of Bitrus Andrew.

“We figured that they were killed on the farm and their bodies were thrown in a river around the area, but then they were swept by water tides, so their bodies ended up around Lau,” Bitrus told HumAngle.

He photographed the corpses and reported the case to the police. Authorities promised an investigation, and security officials were later deployed to the area.

Bitrus misses his nephews. Having raised them, he said they were like his children and had assisted him all their lives on the farm.

The recovery of the four bodies ignited outrage in the Tshobo community. Enraged youths prepared to storm Bachama-dominated Lamurde in retaliation, but security operatives averted the attack.

“There is nothing I want more than peace. If there is a way the government can come into this matter and bring an end to this situation, then they should do so because there’s a lot of tension,” Bitrus said.

This attack echoes a broader trend. In July, HumAngle reported on how the once-peaceful Lunguda and Waja communities in Adamawa have clashed almost every farming season over land, resulting in deaths and destruction of properties. The Bachama-Tshobo conflict appears to fit the same pattern, communal relations collapsing under the weight of unresolved disputes over land and identity in the region.

Severed ties

The conflict has not only destroyed property but also fractured identities.

One of those caught in the middle is 56-year-old Micha Ibrahim. His father is Tshobo, and his mother is a Bachama woman, but he grew up with his siblings in Rigange and even served as the community chairman.

“When my father died, he wasn’t taken to a Tshobo community. He was buried in Rigange. This shows the deep bond we share. I was raised with the Bachama language, and I know every culture and tradition,” he told HumAngle.

On the night the violence broke out, Micha was away in Numan. His son called to tell him youths were clashing in Rigange. By the time he returned the next morning, his home had been reduced to ashes.

“My seeds, my foodstuffs, my goats and everything were razed,” he said.

Yet, the loss of his property was not the hardest blow. Micha, who had chaired the Bachama-dominated Rigange community for over a year, was stripped of his title and exiled in July.

“When they heard that I had arrived that Monday morning, some elders from the Rigange community stormed my house and seized my phone. They said I was never one of them. They said I was their enemy. They said I was from the Tshobo bloodline after all,” he told HumAngle.

“Meanwhile, my house was burnt in the raid by Tshobo youths, so how do I have a hand in this?” He paused and sighed with his palms spread open.

Micha left Rigange that same day after hearing rumours of a planned attack on him. He has been living with his elder brother since. While his wives and children remain in Rigange, Micha said he won’t dare go back.

“I talk to my family every day on the phone. They are doing okay and are unharmed, but I don’t know what fate awaits me,” Micha said.

But he wants to go back home.

“Rigange is the only home I know. I can’t be relying on my elder brother’s support before I send tokens home. My wives and children need me, and with everything destroyed in the raid, especially our seeds, they are suffering,” he said.

Micha explained that silos of grain stored for planting were burnt across Rigange: “I don’t think there’s anybody in Rigange who was able to plant as we speak. My wife told me that there’s a lot of hunger back home.”

In August, he petitioned the police commissioner in Yola, the Adamawa State capital, who visited Rigange in an effort to mediate. But the community rejected Micha’s return. “They insisted that I was a Tshobo man living with them and they no longer trust me or want me there,” he said.

Micha is still waiting, his patience thinning.

Strained lives

Two months on, displaced residents from both communities have begun returning to their homes. However, some individuals are still staying with relatives in neighbouring areas. Security personnel continue to patrol the affected zones. Yet beneath the surface calm, relations remain tense, as neither group uses the other’s route.

“One of our greatest challenges is the freedom of movement,” Hyginus Mangu, leader of the Tshobo community, told HumAngle. “For instance, we have local government workers across our villages who go to work at the council secretariat at Lamurde, but from the time of the incident till date, none of them has gone to work.”

“There is no proper assurance that they can go to work and return safely,” he noted.

The usual rhythms of trade have collapsed. “The Bachama used to bring items to our market, and we also took goods to theirs, but now, we no longer do that. They don’t come to our side. Everyone is scared. Nobody wants to trespass,” he added. Even voter registration for the 2027 general elections has been disrupted because Tshobo villagers cannot safely reach registration centres in Lamurde.

Healthcare access has suffered, too. Tshobo communities had long depended on clinics in Lamurde town, but those facilities now feel out of reach. “There are lots of private clinics and primary healthcare centres in Lamurde, but we are scared of accessing them,” said Hyginus.

Joy, who works at a primary healthcare centre in Lamurde, said she has not reported for duty since the crisis. “I’m not alone,” she said. “Health workers from my community don’t want to trespass on anyone’s boundary.”

As a result, children missed this year’s Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention exercise, which usually runs from June to August. “Healthcare workers from Lamurde didn’t come to Wammi and other Tshobo communities, and on our part, we couldn’t take the children to the clinic due to fear,” she said.

She worries about children needing urgent care: “There are children right now that we are managing at home who require blood transfusions and other drugs, which we can’t tackle at home due to inadequate resources, but we are scared of taking them to the hospital. This is my greatest concern.”

Morrison says he has close friends in Wammi but no longer visits. Bachama farmers who once cultivated land near Tshobo villages have abandoned their plots. “We are all avoiding each other’s territory,” he said.

The state government set up a peace committee and dispatched officials to both communities. But Hyginus is dissatisfied with the process.

“I was expecting them to invite both parties so we could sit down together and discuss our problems and then think of solutions, but they met us individually. We didn’t have a proper dialogue, and as it stands, nobody knows what affects the other,” he said.

Several residents who spoke to HumAngle said the government should hasten reconciliation so that movement between communities can resume without fear of attack.

A violent conflict ignited over farmland disputes in Adamawa, Nigeria, resulted in extensive destruction and community displacement, particularly impacting the Bachama and Tshobo ethnic groups in Lamurde.

The violence began with an unresolved quarrel and led to 53 homes destroyed, deaths, and displacement of residents to neighboring areas. The once harmonious coexistence between the ethnic groups has been severely disrupted, affecting socio-economic practices and essential services, including healthcare and trade. Although security measures and peace efforts have been established, underlying tensions persist, and the affected communities remain divided and in fear.

Residents urge for expedited reconciliation and restoration of normalcy by the government to alleviate ongoing strains.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter