Knifar: Family Stricken Over Detainee-TB Patient Abandoned In Borno Hospitals

Ina, an internally displaced woman in Borno State, visited the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (UMTH), in May 2019, with her husband who was later diagnosed with chronic kidney disease. That was when they met Adam Bulama Modu. Adam, a detainee at the Maximum Security Custodial Centre in Borno, had been at the hospital for over a year because of a lingering problem of abdominal tuberculosis.

He told Ina about his condition and urged her to inform his wife, 20-year-old Falmata Alhaji, also an IDP at the state’s Dalori II camp. First, she was excited to learn that her husband was alive as she had not heard from him in about four years. But then, she hesitated. She was afraid he would be taken back to the prison if the warders saw them together.

She quickly sent information to Adam’s mother, Aisa Aje, who was in Banki and they both went to UMTH. They remember shedding tears when they saw their husband and son. They informed him that his father had died in Bama in 2018 after a battle with hypertension and shared other family-related updates he missed owing to his forced disappearance.

Thousands of men, like Adam, have been arbitrarily profiled, arrested, and locked up without trial based on the allegation that they are members of the terrorist organisation Boko Haram. Oftentimes, they were arrested as a group soon after they escaped from territories initially under the control of the insurgents.

Between 2016 and March 2020, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 3,559 people were released from various detention centres after they were cleared of links with the armed groups. Some had spent up to five or six years without access to their families before their release, and many are still in detention.

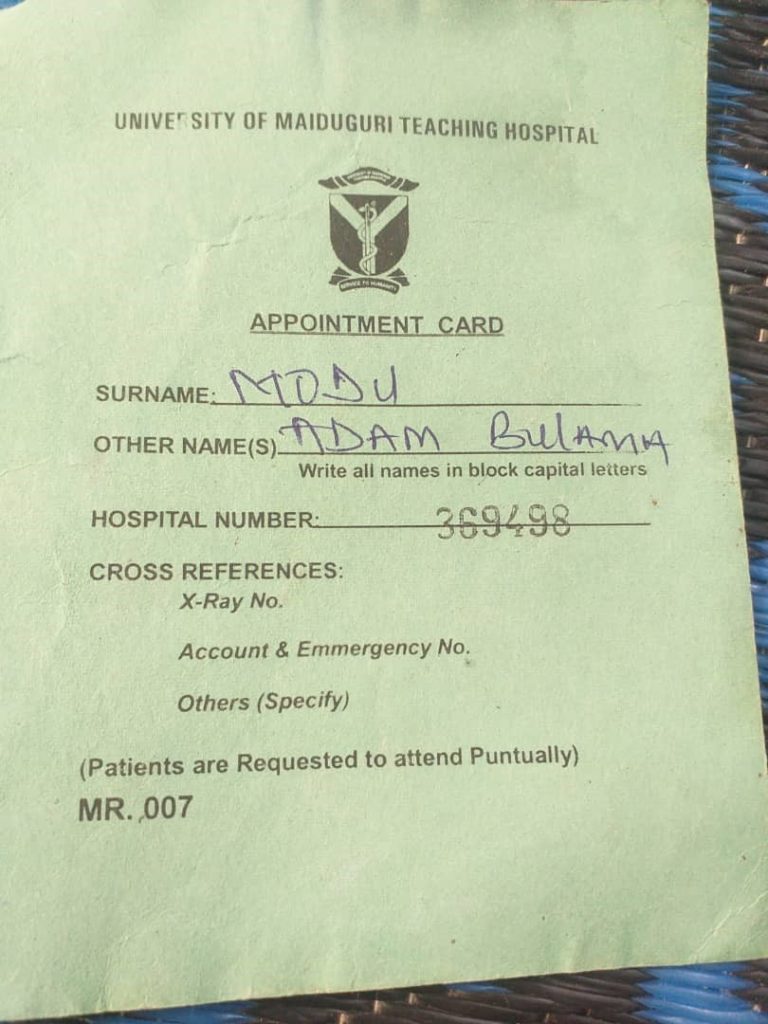

Documents studied by HumAngle showed that Adam had initially been admitted at UMTH on September 16, 2018 with hospital number 369498, and had been discovered to show signs of progressive abdominal swelling. The doctors had recommended that he be placed on an anti-tuberculosis treatment. On May 28, 2019, the result of his abdominal CT (computed tomography) scan was released confirming the diagnosis.

At the hospital, one of the warders told Aisa she could take care of her son but had to be discreet. Whenever prison officials arrived, she should hide or pretend not to know Adam, he advised. And when they left, she could resume her motherly responsibilities. But there was one problem. Adam was only being cared for by the family. The custodial centre seemed indifferent about his well-being.

“When we were there, there was no medicine. If they wrote any prescriptions, nobody was buying. So, we decided to complain and see the Red Cross,” Falmata recalled.

According to her, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a humanitarian organisation that assists victims of conflict, replied that they were not aware of the case. Upon meeting with one of the prison officers, a detention delegate of the organisation said they were not responsible for paying medical bills of detainees and could only mount pressure on the government to act. But the government seemed unwilling to, blaming its inaction on a lack of funds.

“That time, they said they didn’t have money to buy [drugs] so we contributed,” Falmata said. Adam’s brother who worked in Lagos had sent N40,000 and a total sum of N54,000 had been raised and given to one of the warders keeping watch at the hospital.

“They only bought four injection vials and other medicines and said if his condition changed, they should give him the injection. I think they spent the rest of the money.”

The custodial centre also did not provide food the entire time Adam was at UMTH. His wife and mother had to cook at the IDP camp and take food to him regularly. At some point, the prison officials finally supported with 10kg of rice, 15kg of beans, dry fish, pepper, and some condiments.

Aleksandra Mosimann, ICRC spokesperson in Nigeria, confirmed to HumAngle that they mediate between families and prison authorities, but said their findings cannot be disclosed in order to maintain the trust and support they enjoy from the parties.

“Every case is different. We work for the best interests of the detainees based on international laws and standards. It is not only here we work like that. We work like this with the prisoners who are in Iraq, in Yemen, in South Sudan, in South America, it is the same working modality,” Mosimann replied, when asked if the ICRC has a special protocol when it comes to footing the hospital bills of detainees.

The humanitarian organisation promised to follow up on and address the case.

Meanwhile, HumAngle learnt from Adam’s family that, prior to their visit to the hospital, he had been relying primarily on the goodwill from hospital staff and other patients in getting food.

“Later, the hospital management said there was no use of him remaining in the facility, after a year. They said they were not buying medicine, they were not doing tests, they were not paying for the bills, and so had to let him go,” one humanitarian familiar with the case told our reporter.

“I don’t know if they have settled the bill. They came one day in January and took him.”

In the first week of October, Adam phoned his family to say he had been admitted at Umaru Shehu Ultra-Modern Hospital in Borno but advised them not to visit. Again, they learnt the Nigerian Correctional Service (NCoS) was not buying prescribed drugs after tests were conducted. The family took it upon themselves to visit pharmacies to get some of the medicine. They also went to the hospital ward with food and local pap.

It was discovered during a visit to the hospital on the evening of October 9 that he had again been taken away without prior notice to his family. The wards at Borno State Specialist Hospital were checked but he was nowhere to be found. A source within the custodial facility told this paper that his premature discharge was due to the lack of funds to pay for his treatment. (HumAngle reached out to the UMTH Head of Information, Justina Anaso, who promised to confirm the nature of payments from the patient’s records. This report will be updated once that happens.)

“His health was fine before he was detained at Bama Prison,” Aisa said. She added that, while he was at UMTH earlier, though his stomach was unusually big, he was considerably strong, “the disease was not worrying him”. But weeks ago at Umaru Shehu hospital, his health had worsened.

“He was not able to stand by himself. I had to assist him,” she explained. “When we visited Umaru Shehu, he said, mom, I thank God for allowing us to see each other this second time. Pray for me so I can become well.”

HumAngle called a helpline of the NCoS on separate days in October to confirm if the agency was aware of Modu’s case. The first time, the agent promised to provide feedback within 30 minutes but did not call back. The second time, our reporter was advised to send an email with additional information. A reminder has since been sent but neither the original email nor the reminder has been acknowledged.

* * *

30-year-old Adam hails from Kodo, a town in Banki District, Bama Local Government Area of Borno, where he worked as a farmer and cultivated guinea corn, millets and, during the dry season, onions. Boko Haram insurgents invaded Bama in September 2014 and governed the territory before it was recaptured by the military in March, the following year.

Displaced from their hometown, his family moved to Kulujia, Cameroon, in 2015. The Cameroonian army then transferred them to Banki. After seven days, they were taken to Bama Prison for interrogation. It was at the prison they were separated. The women and elderly were moved to the Hospital IDP camp in Bama while Adam remained at the prison before he was later transferred to Giwa Barracks, a military detention centre in Maiduguri.

For three years, nothing was heard from Adam or about him.

“We know he had been taken to Giwa Barracks but we didn’t know whether he was alive or dead―until his admission at the teaching hospital,” said Falmata.

Giwa Barracks has in the past been severely criticised by Amnesty International and other advocacy groups for holding hundreds of “Boko Haram suspects” without tangible evidence, access to lawyers, and court trials. Based on interviews with former detainees, Amnesty International reported in 2016 that many of the inmates have died as a result of disease, hunger, dehydration, and gunshot wounds.

“The discovery that babies and young children have died in appalling conditions in military detention is both harrowing and horrifying,” noted Netsanet Belay, the organisation’s Research and Advocacy Director for Africa.

The military, however, said the accusations came as a “surprise and shock” and denied that civilians died at the facility. It further described the report as “completely baseless, unfounded and source-less with the intent of denting the image of the Nigerian Armed Forces”.

“The Nigerian Armed Forces uphold the tenets of observance of human right and dignity of lives of innocent individuals as enshrined in the Conventions and Charters of the United Nation which Nigeria is a signatory,” it added.

The same week as the press statement was released, President Muhammadu Buhari assured, during an interview with CNN, that he would step up investigations into the conditions of inmates at the facility.

In an account he later gave at the hospital, Adam said he became sick at the barracks. His stomach protruded abnormally, causing the military to transfer him to the maximum-security custodial centre, which has also been reported as a place where inmates are sexually abused and tortured. Seeing that his condition had to be handled expertly, the prison took him to the Borno State Specialist Hospital. He spent about 40 days at this facility before he was returned to the prison. After a year, he was taken to Umaru Shehu hospital, which then referred him to UMTH.

Abdominal tuberculosis, the disease Adam has been diagnosed with, is a rare form of tuberculosis (TB) that affects the gastrointestinal tract and with symptoms that include abdominal pain, anaemia, weight loss, vomiting, night sweats, and fever. Since it is a contagious disease, one of the common ways of contracting TB is by being in a place where it can easily spread, such as a jail or prison.

TB is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that while an estimated 10 million people contracted the disease in 2019, 1.4 million lost their lives to it. Nigeria is one of eight countries that account for 87 per cent of all new cases.

Most cases of TB are currently cured using antibiotics but medications have to be taken for a long time, roughly six to nine months. According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, it is very important for TB patients to finish their medicine and take them exactly as prescribed.

“If they stop taking the drugs too soon, they can become sick again; if they do not take the drugs correctly, the TB bacteria that are still alive may become resistant to those drugs. TB that is resistant to drugs is harder and more expensive to treat,” the group warns.

“Adam is sick and very young. He is a small boy. They should release him so he can get medicine,” pleaded Fatima Bukar, leader of the Knifar Movement, an advocacy group for wives of arbitrarily detained men.

Knifar, which was established in 2017, has said it is aware of over 3,000 women, like Falmata, whose husbands or other male family members are kept unlawfully by the state at Giwa Barracks, the Maximum-Security Custodial Centres, and other detention facilities, without judicial processes.

Fatima stressed that he was not a member of Boko Haram, especially since his father was a village head and would have been killed by the insurgents for being an illegitimate leader if they found out.

“They don’t have any reason for holding him. Even the Boko Haram members who were taken to Gombe [for Operation Safe Corridor] have returned and we are seeing them roaming about. They released them and those who are not terrorists are being kept in the name of Boko Haram; they have to release him.”

Like her daughter-in-law, 65-year-old Aisa’s only request is for her son to be released and given proper medical treatment. “But if they can’t do that, they should at least hand him over to us so that we can do our part by taking him to the hospital and getting him medicine,” she said.

This investigative report is part of a series under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund and HumAngle Media.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter