Kellu Haruna, Through The Eyes Of The People She Loved And Fought For

Kellu Haruna was pioneer-leader of the Knifar Movement founded after her husband and thousands of IDPs were detained in 2015 in Borno, northeastern Nigeria. She died in 2019, still steadfast in her advocacy. Her husband has just been released. We spoke to him, their children, Kellu’s sister, and friends.

On the day that Kellu Haruna received video evidence that her husband was alive and being held at the Borno Maximum-Security Prison, she resolved to gather all the women in the Knifar Movement to attack the detention facility the next day.

She had no weapons nor any intentions of violence. Only rage.

“She said to me: do you know what I’m going to do? I am going to rally all these women and tomorrow we will storm that prison and get our husbands out,” her friend and advocacy partner, Uncle Isah* told HumAngle.

For years she had fought tirelessly for the release of the men. She had led the Knifar Movement, an advocacy group of displaced women in Borno whose husbands were arbitrarily detained between 2014 and 2016 on allegations of being members of the Boko Haram terror group, held for years without trial, in conditions that human rights groups have described as atrocious. Kellu had painstakingly organised thousands of the women into a pressure group to demand the release of these men.

She had even gone as far as testifying before the Presidential Investigative Panel in Nigeria’s capital city, Abuja. Before this, she had met with the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) about the detention, sexual abuse, and other human rights violations she and the other displaced people were facing. The prosecutor had promised to look into it.

Kellu had led the group in writing a petition to the National Assembly for the release of their husbands. She had galvanised and helped obtain video evidence from prison wardens, of at least 50 of the men being held at the Maximum-Security Prison, to show their wives who were part of the Knifar Movement, in order to strengthen them and keep them going and hoping.

Nothing quite broke her, yet hardened her, like finally seeing a video of her own husband.

Uncle Isah was not surprised to hear her speak so boldly about protesting at the prison. Kellu had always been full of fire and love in equal measures. It was what kept her going after her parents died when she was only a toddler. It was what kept her fighting after her foster mother and her husband’s mother resisted the idea of them getting married. It was also what kept her undaunted when, years later, her foster mother mocked her for fighting so tirelessly for her husband’s release.

“The woman would say to her: A man? You are going through all these troubles for the sake of a man? If it was you who was locked up, you think he would do the same for you? He would have married someone else by now,” Kellu’s sister, Fatima Abba, tells HumAngle.

These were words that could have bent the course of a weak heart. But Kellu did not have a weak heart.

Of love and devotion

Kellu was four when she became an orphan. She was then taken to her aunt’s house in Andara, Bama Local Government Area (LGA) to live. She grew up calling her mother.

Her new mother had a co-wife and this co-wife had a son named Haruna. They became friends and inseparable. As they came of age, their bond continued to strengthen, until Haruna had to move temporarily to Banki, another town, to carry out his trade. Still, he would visit home regularly and spend time with Kellu. It was during one of such visits he knew he wanted to marry her.

The idea was resisted by both their mothers. In the open, the women claimed they were averse to it because the children had grown up in the same household and were basically siblings. But when each was alone with their child, they made it clear it was only because they had contempt for each other.

“My mother would say to me: ‘How can you want to marry that woman’s daughter? She is an orphan with a weak lineage. Out of all the girls in this town?’ And her own mother would say the same to her in private. It was just the usual enmity between co-wives,” Haruna tells HumAngle.

In the end, they got married. Haruna regards it as the best decision he has ever taken.

“Anything that I knew she hated, I stayed away from it. And anything that she knew I did not like, she stayed away from it as well,” he remembers. “We loved and served each other. We were devoted to each other.”

Together they had four children and lived peacefully in Andara.

Then, in 2015, Boko Haram took the village. They razed buildings and started ruling over the people.

“They surrounded the entire village and made sure no one could leave. They imposed so many laws on us: our women were never to leave the house, they were to stop helping out on the farms, stop fetching water, stop going to the market. It got to the extent that when some people from the village attempted to escape, they were captured and then executed.”

Uncle Isah chuckles sadly as Haruna speaks. “He speaks exactly like Kellu,” he tells this reporter. “They have the same mannerisms.”

Haruna smiles before he continues his narration.

He explains that many times, whenever he and his brothers sat in the compound to eat, they would be attacked by members of the terror group and their food would be taken from them. Yet they were expected to eat in the open.

When Kellu realised he was not getting enough food to eat because of this, she began to reserve a hidden portion for him.

“At night when I came inside the room to sleep, she would give it to me to eat…”

His voice catches in his throat, his shoulders quake slowly, the tremors from the memory overwhelming him. Then, he breaks into tears.

Trouble…

When he regains his composure, Haruna begins to talk about the oppression of the Boko Haram rule; how they had waited for soldiers to take back the village.

Finally, news got around that the Nigerian army was recapturing Kumshe, a nearby town that had also fallen to Boko Haram. The unrest among the insurgents emboldened them to dare to sneak out of the town. He and his extended family set out at 2 a.m. As they journeyed, they realised they were not alone. Many residents in the town had also taken advantage of the situation to attempt to escape.

It was a long journey. They ran into the terrorists who then began to shoot at them sporadically. In the ensuing disruption and fear, they scattered.

“Women ran to one side and men ran to the other.”

It was the last time he ever saw Kellu.

As he attempted to escape with his companion, a young man he had met that night, they ran into soldiers who then led them to Banki where they were locked up. Their women arrived there the following morning. Kellu was one of them. He did not see her.

“I did not see her. But I was told she came looking for me. She was told that I was part of the men locked up inside.”

Knowing he had not done anything wrong, he was confident he would be cleared the following morning and he would reunite with her and the kids. Things went differently.

“In the morning, we were blindfolded instead and taken to Bama where we were detained. We were so many. We were beaten up and tortured.”

In the middle of that, he said, the soldiers pointed to a well in the prison.

“They said ‘you Boko Haram terrorists. You are the ones who have been killing our brothers and dumping their bodies inside that well. If we like, we could dump your own corpses into that well too.’”

It was only then they realised the reason for their detention: they were suspected of being Boko Haram terrorists. No one had bothered to let them know before then.

Thousands of IDPs like them would be detained in similar ways in the coming months and years.

How do people remember Kellu?

“Whenever my sister starts something, she sees it through to the end, no matter what. She will see it through and let whatever wants to happen happen,” Fatima, Kellu’s sister, tells HumAngle.

“Since we fled Andara together that day, we never left each other’s side, until her death.”

After that night in the bushes when gunshots from the terrorists disrupted the course of their journey and their life, they found their way to the prison in Bama searching for both their husbands. As they stood outside, they saw many of the men, blindfolded, being led out. People said they were being taken to Banki.

From there, the women were taken to the Bama Hospital Camp. It was a hospital that had been mostly burned down by Boko Haram insurgents and had become non-functional, and was now being used as an IDP camp.

“I was heavily pregnant. There was no food. My sister would go out and look for food and bring it to me. One time she did menial jobs and earned enough money to buy grains we could grind to make pap with.”

Even though everyone was hungry, Kellu insisted the grains were not to be used. She was preserving it for when Fatima eventually gave birth, which would be any day now, so that she could have something to eat afterwards.

“She said to me: ‘When you give birth, I will make pap for you with the grains’ … I did not feel good that people were starving because of me.”

The starvation in Bama at the time was severe, with as many as 30 people dying in a day at some point, according to multiple people HumAngle spoke to.

“I convinced her to let us use the grains especially because of our aged mother. She agreed. She was getting sick by this time so I had to grind the grains myself with stone and then made the pap. We all drank it.”

The next day, Fatima gave birth.

“My sister took care of me.”

Until she got sick herself. Kellu got so sick that her body started to swell up. It was during that time aide workers from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) came to the camp to take sick people to the hospital.

“Not all sick people were allowed to go. My sister wasn’t. Then a white woman saw her through the bar gates and insisted that she be brought along to the hospital as she was obviously sick.”

Kellu was sick on and off during the years that followed. Those years were also her years of relentless advocacy. In fact, on the day she mobilised certain members of Knifar to travel down to Abuja to testify at the Presidential Investigative Panel, she had been on admission at the hospital. She had left the hospital bed to make sure she made it to the panel.

Kellu’s children remember those days in tears. When they attempt to talk about her advocacy, how proud and happy they were, and how hopeful they were that it would yield something, they start crying. Yagana Haruna is 14 and Fatima Haruna, 12.

“We felt happy with her advocacy. We wanted our father to come home…”

Kellu’s death

The day Kellu’s protest at the prison premises after seeing a video of her husband was to be held, Uncle Isah arrived at the IDP camp to meet her. He saw her immobile in her tent, in a mosquito net, groaning.

“She was groaning in pain, she could not move,” he tells HumAngle. “We immediately got her to the hospital. It seemed like a cardiac problem.”

They would later realise she was suffering a stroke. The signs had begun to manifest after she saw the video of her husband the day before.

“She had been very stressed.”

For two days she was there at the hospital and seemed to be getting better. But her arm was immovable.

A few days later, she died.

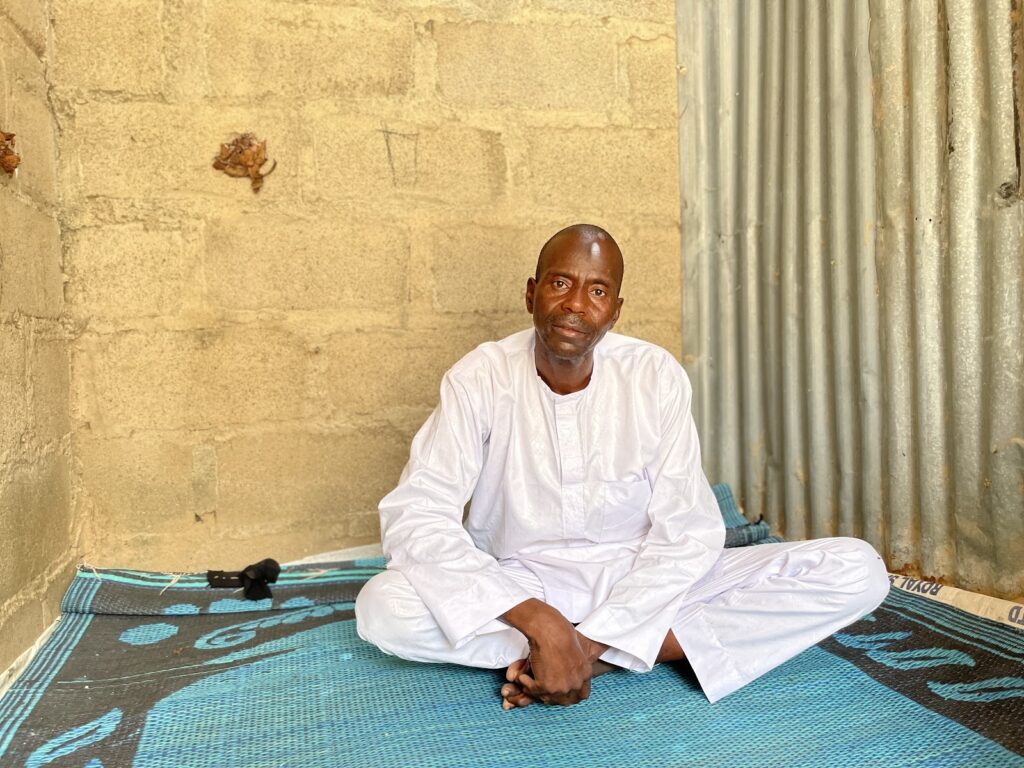

Now, seven years since she and her husband and family left Andara, and four years after she began to advocate for him and other men, he has been released.

“Throughout this whole time, I was never tried in court or anything,” Haruna says.

He was held through various detention facilities; from the notorious Giwa barracks to the Borno Maximum-Security Prison, to the deradicalisation camp for Boko Haram deserters in Gombe State. He has the same experience as the approximately 2,000 men who were detained in the same fashion as him— There are over 2,000 women in the Knifar Movement. This figure is obtained from the current leaders of the movement, Yakura Kumshe and Fatima Bukar. It is also corroborated by a statement from Amnesty International, which has reported on the movement.

Haruna’s release

“The prison officials used to ask us questions,” Haruna says.

“They also used to attempt to get us to ‘surrender’, especially at the deradicalisation camp in Gombe. But I kept insisting that I was not a Boko Haram terrorist. They would write statements down and ask me to sign. I never knew what they wrote because I am not literate, and they never translated.”

This was despite Nigeria’s laws providing through the Illiterate Jurat that an ‘illiterate’ be read out a translation of their statement or any document purported to be written by them, before being asked to sign.

Haruna’s release hardly feels like victory for him.

Before the insurgency, he had a full, hale and hearty family. Now, the woman he loves is gone. His mother is gone too. His stepmother, gone. Two of his siblings whom he had been detained with had also died in detention. He has returned home with no money nor means of livelihood, and an almost unbearable weight of responsibilities for his children. Even ‘home’ is no longer home. It is an IDP camp.

Asked if he had ever thought that Kellu would advocate for him in the manner she did, Haruna says yes. He just did not know she could go to the extent that she did.

When he and the children are shown a video of her from YouTube, where she is seen speaking and advocating, Haruna looks with disbelief at the screen. Then he breaks into tears.

He and his daughters weep uncontrollably for a long time.

“We should never have left Andara,” he sobs.

“We should never have left Andara.”

*Names marked in asterisk have been changed to protect the identity of persons interviewed.

This report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter