Kainji Lake and the Dangerous Redrawing of Nigeria’s Security Map

As climate stress, poverty, and border neglect converge, a once-protected landscape turns into a sanctuary for terrorists, linking Nigeria’s northwest to Sahelian violence and reshaping the country’s security map.

The routine of gently but skillfully pushing wooden canoes into the water body at the shores of Kainji Lake each dawn has been part of the lives of generations of fishermen in North-central Nigeria.

The lake was not always calm – vigorously exhaling and flooding the banks, then intermittently receding – but was inevitably connected to the lives that many communities have held firmly to across Kebbi, Niger, and Kwara states.

Today, that ancestral connection between the communities and the lake is evaporating rapidly. And it is not merely ecological. In some villages where government presence is absent, and terrorists have assumed authority, fishermen now wait for permission from non-state actors before casting their nets. In other areas within the Kainji region, they pay informal levies to armed groups operating from the forests. For decades, Nigeria’s national parks were imagined as spaces apart: buffers of nature against human pressure and political failure. Sambisa Forest shattered that illusion long ago when the Boko Haram terror group took control of it, transforming from a conservation zone into the most notorious symbol of jihadist insurgency in the country. Now, further west, a quieter but no less consequential transformation is unfolding.

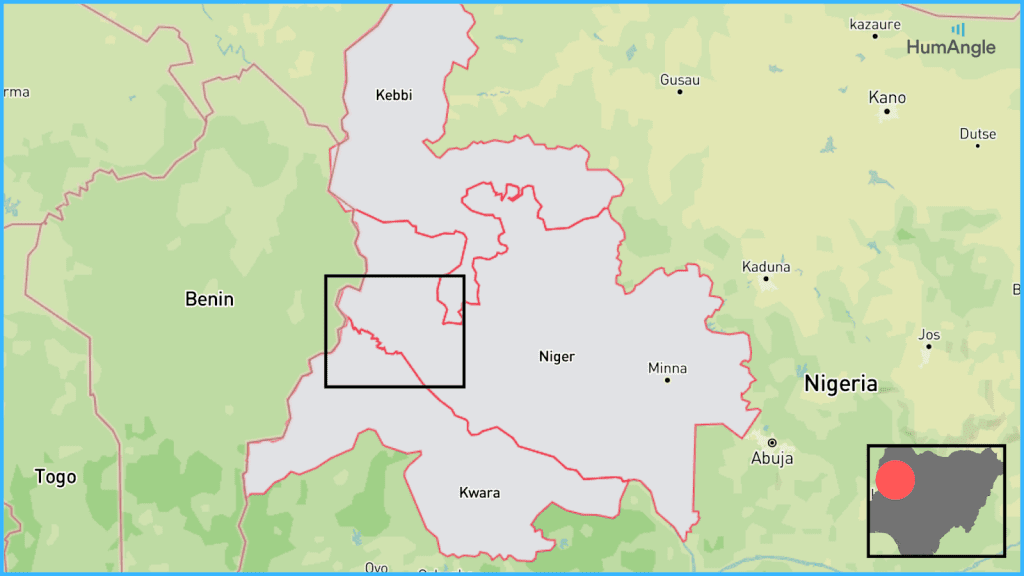

The Kainji Lake National Park (KLNP), sprawling across three states and bordering Benin, has slipped from a wildlife sanctuary into a strategic corridor where poverty, climate stress, criminal enterprises, violence, jihadist ideology, and Sahelian militancy intersect.

A corridor

Security analysts increasingly describe Sambisa as a “fortress-base” model of insurgency: entrenched, ideological, territorially assertive. Kainji Lake fits a different and more elusive pattern—a “corridor-node” model.

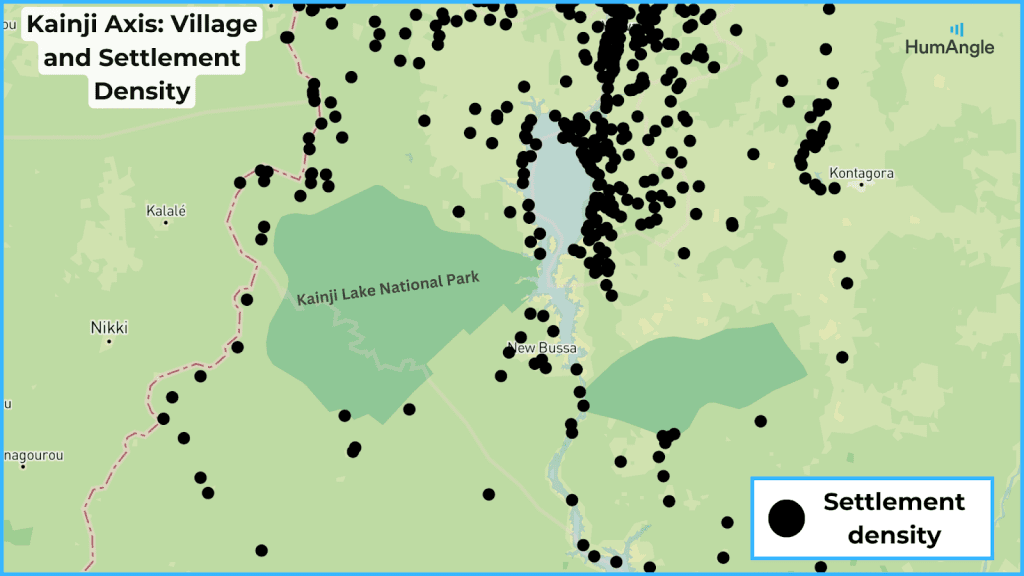

Here, armed actors do not raise flags or announce governance structures. They pass through, networking, training, recruiting, and trading, before vanishing. The park links Nigeria’s troubled North West to the Middle Belt and, increasingly, to the destabilised Sahel. It connects Kebbi to Benin Republic’s Alibori and Atacora regions, Niger State to Niger Republic’s Tillabéri zone, and local grievances to transnational jihadist ambitions.

This distinction matters. Sambisa attracted relentless military pressure for more than a decade because it became a visible symbol of territorial breach. Kainji Lake did not. It appeared peripheral, quiet, manageable. In that absence of sustained attention, the park matured into something arguably more dangerous: a fluid connector for multiple armed actors rather than a single-group stronghold.

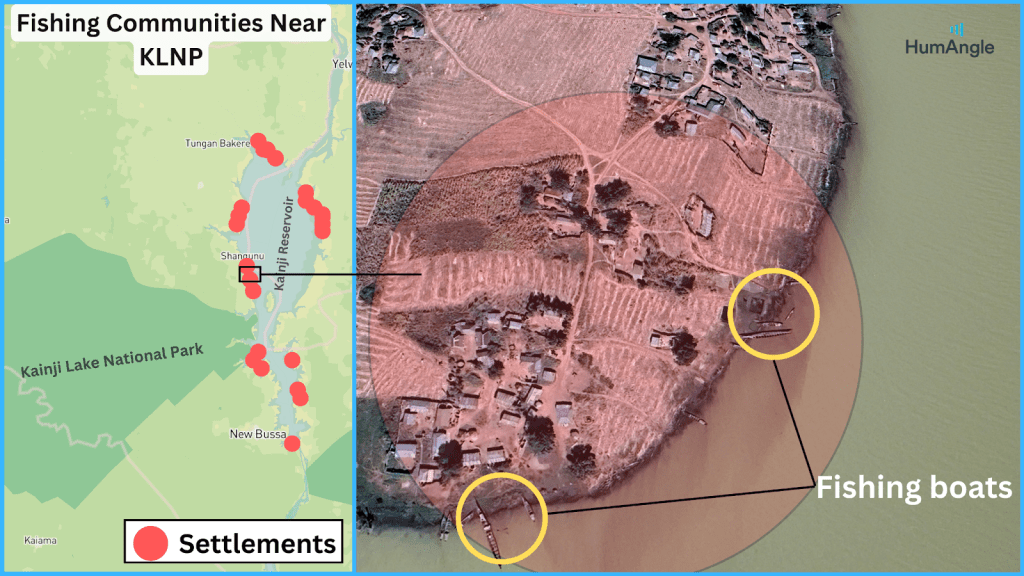

Communities along the lake, from Yauri and Ngaski in Kebbi to Borgu in Niger State and Kaiama in Kwara, depend on a fragile interweaving of fishing, floodplain farming, pastoralism, and cross-border trade. Fishing sustains thousands of households. Smoked and dried fish move through informal networks to Ilorin, Ibadan, southern Niger, and beyond. Seasonal farming follows the lake’s unpredictable pulse: millet, sorghum, maize, rice, and cowpea are cultivated on land that appears and disappears with the water’s rise and fall.

Pastoralism runs through it all. Herders move cattle along routes that long predate colonial borders, grazing across Nigeria, Benin Republic, and Niger Republic as if the lines on maps were suggestions rather than laws. Weekly markets in Bagudo, Wawa, Babana, Kaiama, and Borgu draw traders from Benin’s north and Niger’s Tillabéri. Grain, livestock, fuel, kola nuts, dried fish, and cloth circulate through these hubs. Some of it is smuggling.

These networks matter because armed groups do not need to invent new pathways. They insert themselves into existing ones. The same tracks used by herders and traders now carry militants, arms couriers, recruiters, and ideological emissaries.

Climate stress as an accelerant

Climate change has exacerbated existing security vulnerabilities around Kainji Lake.

Erratic rainfall patterns and fluctuating water levels have made fishing yields unpredictable. Floodplains that once reliably supported seasonal farming now vanish early or arrive late. Pasture availability shifts without warning, intensifying competition between herders and farmers. Each shock further compresses livelihoods, forcing households to adapt through debt, migration, or risk-taking.

In this environment, armed groups offer something deceptively valuable: predictability. Access to grazing land. Protection from rivals. Permission to fish or farm. Even informal dispute resolution. Where the state provides uncertainty – sporadic enforcement, unclear rules, delayed response – armed actors provide immediate answers, enforced by violence if necessary.

Climate stress, in this sense, is not just an environmental issue but a governance crisis multiplier.

Fieldwork conducted by HumAngle across several local government areas in Kebbi, Niger, and Kwara states identified at least five active extremist factions operating within and around the park. These include the Mahmudawa (Mahmuda faction), Lakurawa, elements of Ansaru and Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS) led by Sadiku and Umar Taraba, and a newly emerged cell linked to Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin.

The groups do not operate in isolation. Many originate from northwest Nigeria and southern Niger, with local cover, as they undertake terror attacks in distant locations and return to their various hideouts within the region. What has emerged is a hybrid threat ecosystem where ideology, criminality, climate stress, and grievance reinforce one another.

Brokers, enforcers, and ideologues

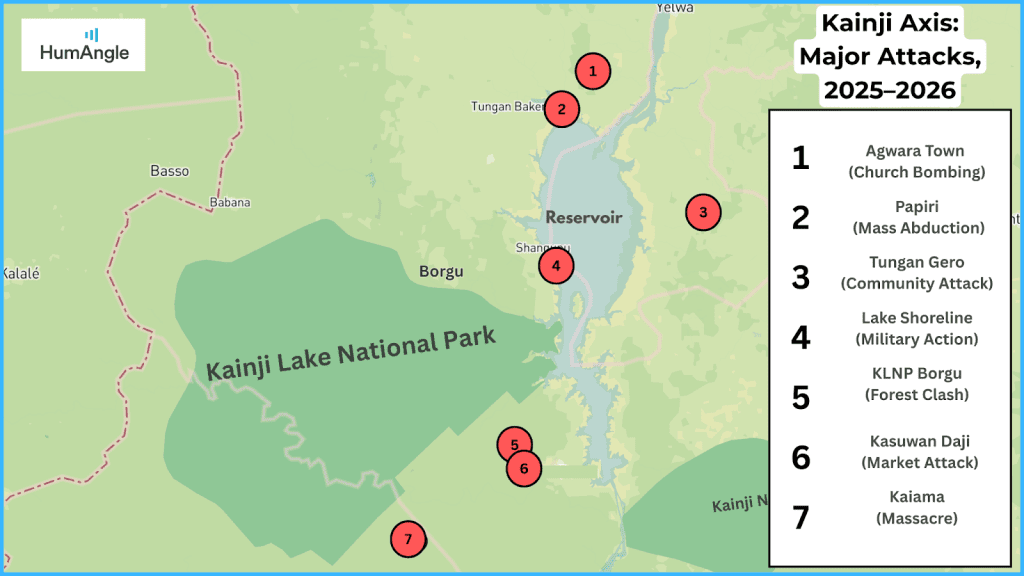

The Mahmudawa illustrate the new logic of this ecosystem. Despite sustained air and ground operations by the Federal Government between September and December 2025, the group remains influential. Fragmented into smaller camps, some closer to the Benin border, they act as brokers linking criminal networks of jihadist actors. They facilitate training, arms movement, ransom negotiations and sanctuary for fighters arriving from outside the region.

Official claims regarding the arrest of their leader, Malam Mahmuda, remain unconfirmed in border communities, where continued attacks and coordinated leadership are still attributed to the group.

If the Mahmudawa are brokers, the Lakurawa are enforcers. With an estimated 300 fighters, they have become one of the most active jihadist–terrorist hybrids affecting Kebbi’s border communities. Operating from within and around KLNP, they routinely launch incursions into Bagudo and Suru LGAs, combining attacks on military targets with ideological messaging aimed at delegitimising the Nigerian state.

Their leadership shows signs of Sahelian exposure. Their fighters are drawn from local nomadic tribal networks and northwest terrorist pools. Kebbi, long considered peripheral, is now firmly part of the frontline.

The relocation of Sadiku and Umar Taraba, both veteran jihadist operatives, to the Kainji axis in 2024 marked a shift. Their presence injected technical expertise into a space previously dominated by loosely organised armed groups.

IED knowledge, structured training, and a sharper focus on high-value targets followed. Collaboration with criminal terrorist groups deepened. The abduction of foreign nationals near Bode Sa’adu illustrated this fusion starkly: JAS elements, Mahmudawa fighters, and allied terrorists executing a single operation where ideology and profit were indistinguishable.

JNIM’s shadow on the lake

The most alarming development emerged in late November 2025: the appearance of a group believed to be affiliated with JNIM along the Kebbi–Benin border corridor.

Witnesses describe predominantly foreign fighters, many believed to be Tuareg, moving at night in disciplined formations, wearing military-style uniforms with turbans on their heads, and engaging communities with a calculated restraint unfamiliar to local armed groups. So far, they have avoided major attacks.

That restraint is likely strategic.

Their presence suggests Kainji Lake could become a staging ground for Sahelian expansion into northwestern Nigeria — a shift that would fundamentally alter the region’s security calculus. Unlike local groups, JNIM brings external financing, battlefield experience, and a long-term vision.

Communities adapting under pressure

Communities in the lake basin are not passive observers. They are recalibrating in real time. Some negotiate access quietly to avoid displacement. Others maintain layered loyalties, sharing information selectively as a survival strategy. Vigilante groups that once patrolled forest edges retreat under sustained pressure. Traditional rulers face coercion or marginalisation. In certain settlements, schools and community buildings are repurposed by armed actors for operational use.

Access to fishing grounds, farmlands, and trade routes increasingly depends on permissions issued by commanders operating from forest camps rather than on decisions by local councils or chiefs. Authority has shifted, not through formal declaration, but through incremental control of movement and livelihoods.

How conservation and governance hollowed the ground

The transformation of Kainji Lake into a security corridor is as much the product of ideology as it is the cumulative outcome of governance failure layered over decades.

The creation of Kainji Lake National Park in 1976 displaced communities and restricted access to land and water without meaningfully integrating residents into conservation planning. Fishing zones were closed, grazing was curtailed, and farming was criminalised in places where alternatives did not exist. Promised livelihoods rarely materialised.

Park rangers – tasked with enforcing vast conservation boundaries – were underpaid, poorly equipped, and often absent. Their presence, when felt, was frequently punitive rather than protective.

Local governments in Bagudo, Suru, Kaiama, Borgu, and Ngaski remain chronically weak.

When armed violence escalated across the northwestern region, security deployments focused on Zamfara, Katsina, and parts of Niger State. Kebbi’s borderlands were treated as peripheral, stable, and low-risk. That assumption proved costly.

Border governance failed as well. Coordination with Benin and the Niger Republics remains distant, reactive, and politicised. Joint patrols are rare. Intelligence sharing is uneven. Communities know this. Armed actors understand it better.

Armed groups arrived first as guests, then as protectors, and finally as power brokers, filling gaps the state created—sometimes violently, sometimes persuasively.

Poverty caused by the absence of authority

In the absence of legitimate state authority, people seek alternative systems of order. Armed groups exploit this vacuum expertly. They tax, regulate, punish, and reward. In some communities, the question is no longer whether armed groups are legitimate, but whether they are avoidable. Increasingly, they are not.

Once a symbol of Nigeria’s conservation ambition, KLNP has become a largely ungoverned hub exploited by a mix of violent actors: jihadist cells, armed terrorist factions, and transnational militants with roots beyond Nigeria’s borders.

From the northwest’s perspective – particularly Kebbi State – the park functions as a rear operational hub. Armed groups operating in border local governments use it for recruitment, logistics, training, and cross-border movement into the Benin Republic. Its sheer size, rugged terrain, and weak oversight enable a dangerous convergence: criminal armed groups blending with jihadism.

This shift carries national implications

Kainji’s forests and waterways provide mobility, with the lake economy providing revenue streams and border proximity offering escape and reinforcement routes.

While Sambisa became synonymous with territorial insurgency, Kainji signals the maturation of a corridor-based conflict economythat binds Nigeria’s northwest to wider Sahelian instability through forest reserves and lake communities.

When conservation spaces double as conflict connectors, the impact extends beyond biodiversity loss. Human buffers weaken first as communities negotiate survival under parallel authorities. Ecological buffers follow as enforcement fractures and resource exploitation become embedded in armed group financing.

The lake basin lies close to Kainji dam, a critical energy infrastructure, touches sensitive international borders, and anchors trade and livelihood systems that extend deep into the country’s interior.

In 2026, the geographic corridor surrounding the lake and its forest reserves recorded some of the highest levels of mass killings and large-scale abductions in Nigeria. Armed groups operate with increasing confidence, widening their reach across rural settlements and mobility routes connecting Niger State to Kebbi, Zamfara, and beyond toward the Sahelian belt.

The warning signs are not limited to a single park

In April 2025, the Conservator-General of Nigeria’s National Park Service, Ibrahim Musa Goni, told HumAngle that six national parks across the country were overrun by terrorists. Two years earlier, the federal government had created 10 additional parks to prevent further takeovers. However, only four of those new parks are currently operational. In addition to the seven existing parks, only eleven national parks are currently functioning nationwide.

Even where reclamation has occurred, the process is complex. The Conservator General pointed to Kaduna State as an example, describing what he termed a “mutual understanding” between authorities and armed groups.

“They have agreed to resolve their issues,” he said. “[As a result], most of the forest and game reserves, and even the national park in Kaduna State, have today been freed of banditry.” This, he argued, has brought “relative peace” and enabled forest and game guards, including officers in Birnin Gwari, to resume operations.

The National Park Service has also redefined its institutional posture. “The government classified the National Park Service as a paramilitary organisation,” Goni explained. “And as a paramilitary organisation, the act provides that we can bear arms.” Rangers affiliated with the Service have received training from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime to address wildlife crime and respond to terror-related takeovers. According to Goni, this training has strengthened Nigeria’s capacity to confront forest-based criminality linked to armed groups and insurgents.

The approach is not solely security-driven. The Service engages surrounding communities through alternative livelihood programmes, skills training, and starter packs intended to reduce dependence on park resources. “This has, in a great deal, diverted the attention of most of them from the resources of the national parks,” Goni said, adding that it has helped contain hunting and wildlife trafficking.

Yet resource limitations remain significant. “Apart from managing wild animal resources and the plants, we also have to manage the human population,” he acknowledged, noting that the Service cannot meet the needs of every community bordering the parks.

Around Kainji, these gaps are visible.

The Kainji Lake region in North-central Nigeria has seen a shift from being an ancestral fishing and farming area to a strategic corridor for armed groups amid governance failures and environmental challenges.

These transformations are exacerbated by climate changes affecting fishing and farming, alongside the ingress of armed groups who offer predictability in a region marked by poverty and weak government presence. Various militant factions have established a "corridor-node" model here, using existing trade routes for insurgency, smuggling, and recruitment while coercing local communities to align operations with their needs.

The Kainji Lake National Park, once a conservation zone, has become a hub for jihadist operations, blurring the line between ideological warfare and criminal enterprises. Armed factions such as the Mahmudawa and Lakurawa capitalize on the weak state presence, integrating into established networks once used for legitimate trade. This deteriorates regional security, affecting communities’ livelihoods as these groups enforce their control over fishing, farming, and trading operations.

As national parks across Nigeria confront similar threats, solutions include reclassification of parks for paramilitary operations and engaging local communities in alternative livelihood projects to address this intersection of environmental and security crises.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter