Is Landmass Powering Violence In Northern Nigeria? Here’s What The Data Say

Landmass may be contributing to the increasing ungoverned areas breeding terrorism and banditry across Nigeria's northern states.

The steady rise of violent extremism and its resulting conflicts has rendered Nigeria unsafe. In the past decade, the terrorist group Boko Haram, and its splinter organisations, ANSARU and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), have caused the deaths of over 30,000 people and the displacement of another 2.2 million.

HumAngle analysed data suggesting that factors beyond economics and religion are at play. Landmass may be contributing to the increasing ungoverned areas breeding terrorism and banditry across northern states.

Professor of Law and human rights activist, Chidi Odinkalu, drew public attention to this point in a recent interview with the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR). States such as Borno, Kaduna, Taraba, and Adamawa headline the hottest theatres of insurgency, banditry and sectarian upheavals.

Another connection to draw is that they are equally the frontline states in landmass. Kano state, with its heritage of robust, often combustive, religious activism, has remained a sort of a sleeper cell for insurgency. Data shows that Kano—together with Gombe state—profiles the least in terms of landmass in that part of the country.

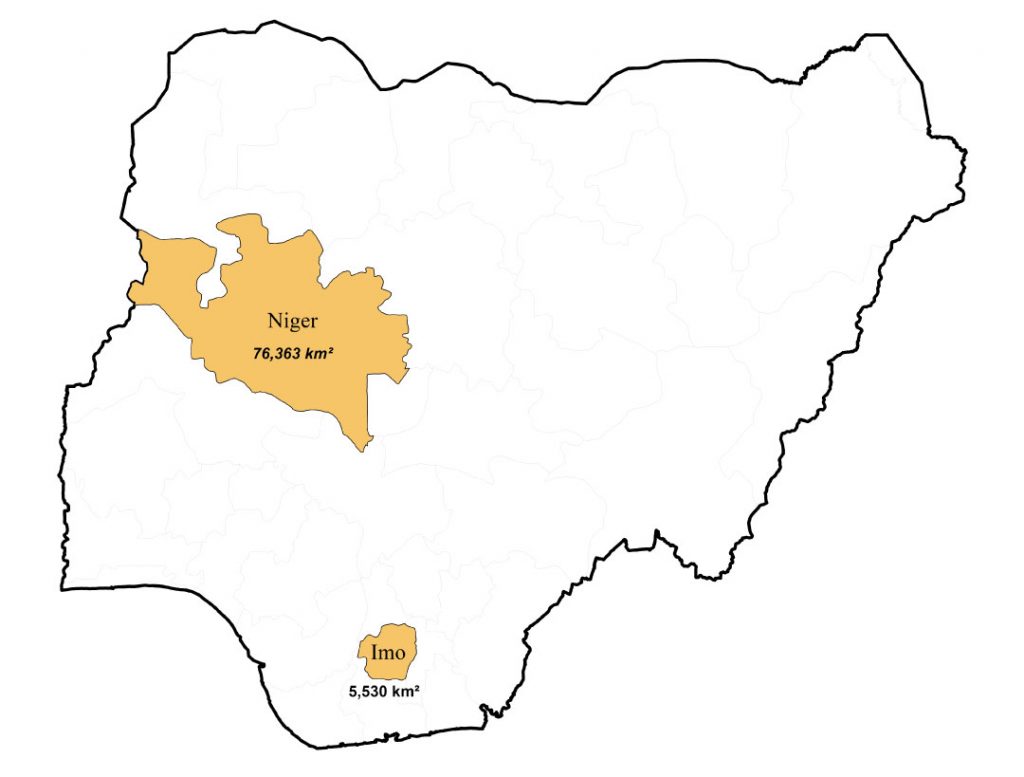

Making a correlation between ungoverned landmass and its breeder feed status for insecurity in Nigeria, Prof. Odinkalu asserts: “Niger state has 25 Local Government Areas and is over 15 times the size of Imo state. Basically, the average size of a Local Government Area in Niger state is close to the size of Imo state.

“What does that mean? You have so much territory, you can’t deploy protection assets effectively. Niger state is over 20 times the size of Lagos state. Lagos state has over five times the number of police assets than Niger (state).”

“So, when you have a crisis, you can’t deploy assets of protection effectively, and any assets you have to deploy are invariably overwhelmed by territory and landmass. They can’t effectively cover everywhere, they are outnumbered. That is the crisis we have in the North.”

Nigeria’s 10 deadliest States also with the biggest landmass and LGAs

To further give perspective on this particular element in the insecurity index in Nigeria, HumAngle looked at the 2010 Annual Abstract of Statistics released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on state sizes as established by the Surveyor-General’s office.

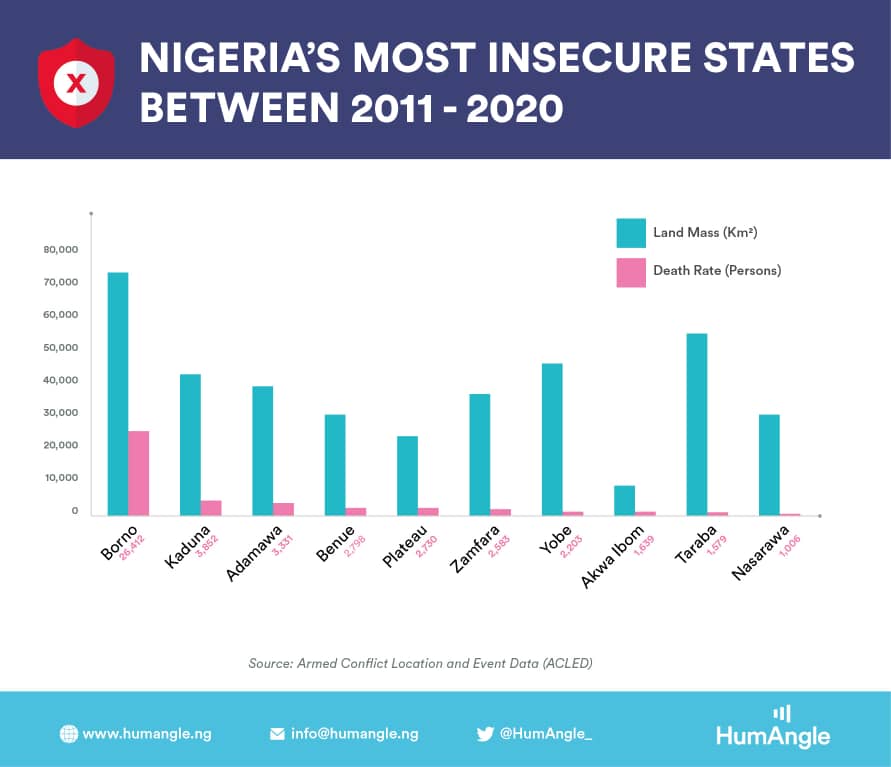

An aggregation of the document’s data and the analysis of casualty figures HumAngle obtained in the various states, between 2011 and 2020 from the Nigeria Security Tracker (NST) and Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) reveal a disturbing trend.

The NST is a project of the Council on Foreign Relations that documents and maps socio-politically motivated violence in Nigeria, while ACLED records data on political violence and killings in over 100 countries. Indeed, ACLED is recorded as the “highest quality, most widely used, real-time data and analysis source on political violence and protest around the world.”

This led HumAngle to examine the records with the Mass Atrocities Casualties Tracking report of 2019 released in February 2020 by the international organization Global Rights, covering terrorist attacks, extra-judicial killings, gang clashes, kidnapping, and more.

An analysis of these various reports highlight the following seven states as among the top ten most insecure states in Nigeria. They include Adamawa, Borno, Kaduna, Nasarawa, Taraba, Yobe, and Zamfara states.

In terms of sheer landmass size—all the states—except Nasarawa, ranked 12th largest, are among the ten largest in landmass in the country. According to the NST, Borno state has the highest number of casualties from politically motivated violence from 2011 to 2020.

Borno is Nigeria’s largest state and has the fifth-largest average LGA size. In terms of death toll, it is followed by Adamawa, Kaduna, Zamfara, Benue, Yobe, Plateau, Taraba, then Nasarawa in that order.

Borno is Nigeria’s largest state and has the fifth-largest average LGA size. In terms of death toll, it is followed by Adamawa, Kaduna, Zamfara, Benue, Yobe, Plateau, Taraba, then Nasarawa in that order.

Similarly, the database from ACLED captures the following as the most insecure states in Nigeria during the same period: Borno, Kaduna, Adamawa, Benue, Plateau, Zamfara, Yobe, Akwa Ibom, Taraba, and Nasarawa. The coloration is nothing different with the data from the 2019 Mass Atrocities report. The following places ranked in the top ten deadliest states: Borno, Zamfara, Kaduna, Katsina, Taraba, Rivers, Benue, Niger, Sokoto, and Kogi states.

Odinkalu offers an answer to explain the curious high-level insecurity in Rivers and Bayelsa, despite it being among the smallest in terms of landmass. He asserts that the states remain insecure because they nearly replicate the ungovernable nature of towns in the Northern states due to their “ungoverned waterways and creeks.”

There are, however, two notable outliers: Kebbi and Kwara, respectively Nigeria’s 9th and 10th biggest states. Kwara has the seventh-largest average LGA size while Kebbi has the 11th. Yet, the NST and ACLED report that Kebbi state is among the safest place in the country. Kwara state is also remarkably safe, allowing these places to hold the ninth and fifth positions respectively in the safe state index. The 2019 Mass Atrocities reports highlight a similar phenomenon between these states, ranking them the third and fourth lowest numbers in casualties.

There are multiple factors

In spite of the statistical trend, using variables such as landmass and ungoverned space may not fully account for the causes of insecurity in Nigeria. In September 2019, the United Nations observed that other continuing and contributing factors include “population explosion, an increased number of people living in absolute poverty, climate change and desertification, and increasing proliferation of weapons.”

The country’s revised National Security Strategy has identified additional factors including, limited capacity in information, communication, and space technology; irregular migration encouraged by porous borders, lack of a reliable central criminal registry, and so on.

Yet, Odinkalu is certain that government presence throughout the country will control the violence. “We have got to make government more effective. We have got to ensure people steal less. We have got to spend less on overheads so that the government can begin to acquire more legitimacy, which is why if you go to Borno state, in some places like Dikwa, what you see is Boko Haram levying taxes and providing services,” he said.

“Those are places where the government should be playing those roles. But now people have made their peace with outlaws and those outlaws have been providing protection. For me, it’s very clear; the insecurity issue is a reflection of a deeper problem, which is malgovernance.

“Unless we are able to address this at the level of governmental systems, we will have this problem and it is going to deepen,” he concludes.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

Highly educative. Excellent effort

Excellent effort

Professor Odinkalu hits the nail squarely on the head when he identifies “malgovernance”, and I would also add, the curious absence and incompetence of government, as factors responsible for insecurity in Nigeria.

For any government to be able to claim sovereignty over any space, that government must be in firm control of, at least three things, relating to that space, namely, its “defence”, “security” and “economy”. Strangely, through their utterances and body language, our government does not seem to be in full control of the first two factors. Nowadays, insurgents, bandits and nomads breach our borders with impunity and do whatever they please within our space and our government either feigns helplessness or makes excuses for their impunity. In some cases, our government officials have sadly either use public funds to mollify these malefactors who trouble us or have dignified them with fraternisation , that is suggestive of an abject surrender of State power and sovereignty to these miscreants. The popular refrain is often that our borders are too porous to police; however, if we cannot prevent unauthorised persons from coming into our country, we should at least have firm control over whatever they do within our country. To begin with, anyone who comes into Nigeria without the requisite authorisation and documentation has committed an offence, and they should be promptly fished out and severely dealt with appropriately, along with whatever crimes they may have committed in Nigeria. This will send a clear message to prospective foreign criminals that Nigeria is not open for their kind of business, however, the moment we start to reinforce their negative behaviour, through our do-nothing approach, we are inadvertently telling them that we are available for plunder.

The only reason why the “land mass” theory of insecurity appears plausible is because we run a reactive security policy and strategy. Modern security thinking is proactive, and hence always one, or more, steps ahead of the enemy. If only we had a proactive security policy and strategy (such that we always have quality and actionable intelligence on our enemies), then our land mass should not matter. E.g. for well over two years now, villages in Niger East senatorial zone of Niger State have been experiencing rampant and savage attacks by, as yet unidentified marauders, with undiscernible motives. What is most intriguing about our inability, or is it failure (?), to solve this security problem is its psychological and strategic implications, to wit, that the Inspector General of Police of Nigeria hails from Niger State and the pivotal location of the area experiencing this attacks – the Niger East Senatorial Zone is home to one of Nigeria’s largest hydroelectricity generating plants – Shiroro and is proximate to two others (Jebba and Kainnji), whilst it also borders the seat of the Federal Government(the Federal Capital Territory) on the south west. One would have thought that enlightened self-interest should have at least motivated our government (if we still have any?) to act decisively to extirpate this insecurity problem, but alas, a curious abdication of governmental responsibility has allowed this insecurity to persist and fester. It is rather tragic that today, Nigeria retains the services of security chiefs, who in a well-governed society, would have long been dismissed with ignominy and / or be answering for their incompetence /negligence / sabotage before a Court of competent jurisdiction!

When our government is not kow-towing to foreign criminals, she is failing to enforce her own laws and bring to heel sacred cows within, who have become a law unto themselves. Additionally, a dysfunctional security policy which effectively places the planning, implementation and control of local security in the hands of a central government that is far removed from the localities whose security they are charged with, is also problematic. Hence, since the federating states do not, and cannot, control what they do not own ( federal security organisations), there is therefore a limit to which they can essentially deploy this organisation to provide security in their jurisdiction.