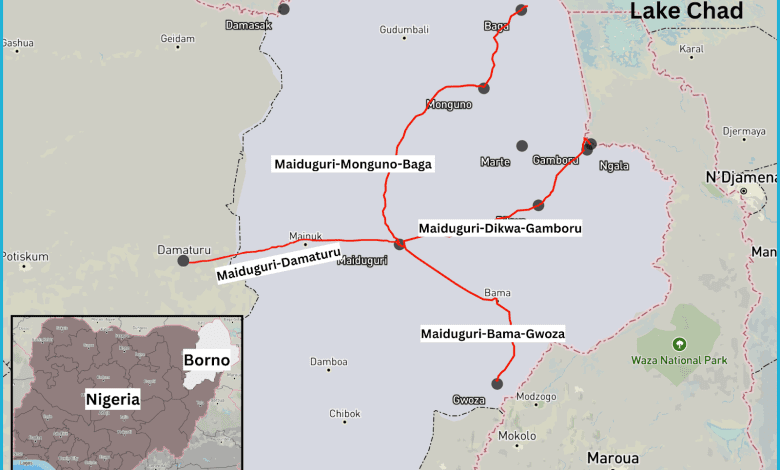

Insecurity on Borno Roads Still Affecting Commerce

For years, traders and passengers moved into Maiduguri without escorts or curfews, until conflict turned these open routes into restricted corridors. Even as calm returns, the roads no longer remain the same.

It was early in the morning, and Yakubu Buba stood in front of his house in Gamboru, northeastern Nigeria, looking towards the horizon. He was not waiting for a vehicle. He was waiting for cattle.

From across the Cameroon border, they came in low, patient herds, hooves lifting dust into the air. Yakubu breathed in deeply and smiled. He enjoys the smell of fresh animal droppings, he says. “It replenishes the soul.”

The herds come daily. “About ten of them,” the 57-year-old estimates. “They are guided into Kasuwan Shanu, where they are loaded onto trucks bound for Maiduguri.”

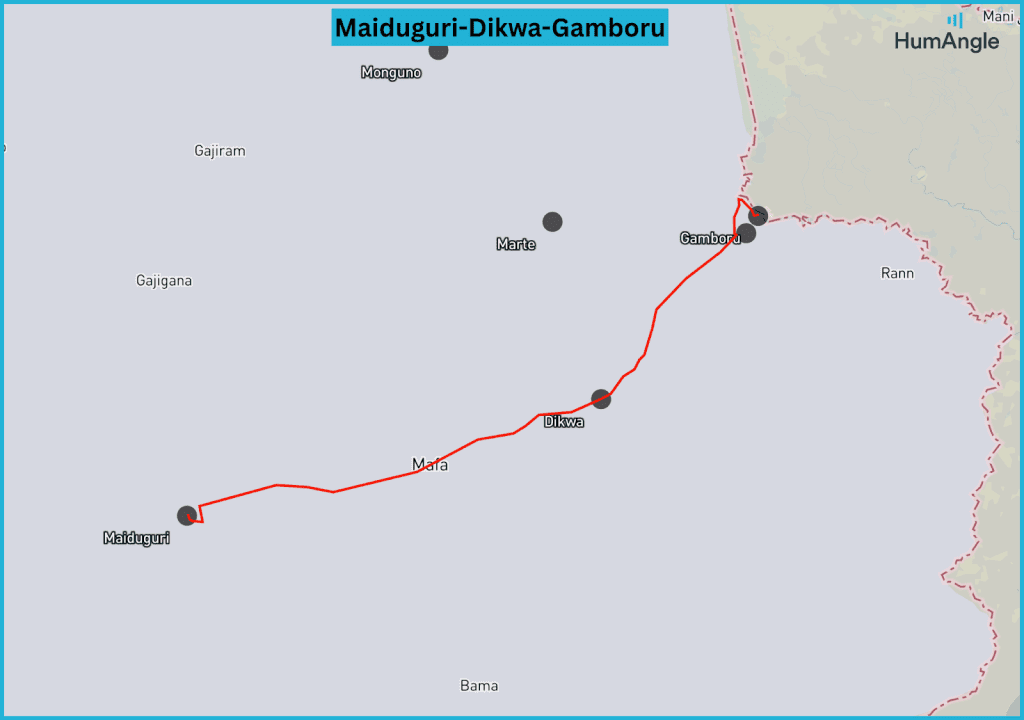

That same morning, he, too, was headed to Maiduguri. A bean merchant since he was 17, Yakubu began travelling the Maiduguri-Dikwa-Gamboru road in 1986, importing beans from Cameroon and selling them onward to traders at the Muna Market who supplied to markets across Nigeria.

Gamboru sits on the Nigerian-Cameroon border in the northeast. A few kilometres away is Ngala, which links Nigeria and Chad. Through these borders, traders export processed goods like flour into Cameroon and Chad, Yakubu says. And when crossing back, they would import beans, sesame, and groundnuts. Animals, in whole or in parts, like hides, are the most imported from these countries, he says.

At the Muna Motor Park in Maiduguri, where I met Yakubu, this pattern was once predictable. Vehicles arrived full and left fuller. Mustapha Hauwami, a 47-year-old driver who began plying the route in 1980, remembers when the park felt like a tide. “We transport traders and passengers to Gamboru and Dikwa daily,” he says. “Most of those coming from Gamboru are Chadian traders.” He drove twice a day, sometimes more.

The pattern got interrupted, slowly. Conflict came, and fear crept in. “It became too risky to travel,” Mustapha says. Checkpoints began to pop up, and movement became impossible without military escorts. “There are at least 20 checkpoints on the road,” Mustapha says. “Importing goods became difficult,” Yakubu adds.

Movements became restricted

The effects were uneven. While Maiduguri’s economy tightened under restricted access, border towns like Gamboru adapted in unexpected ways. Cut off from Maiduguri at the height of the Boko Haram conflict, traders there turned outward. “We relied entirely on Chad and Cameroon,” Yakubu recalls.

Over time, goods from Maiduguri began arriving again, but now as just one stream among many. “They became cheaper in Gamboru,” he said. “Goods were coming from both Maiduguri and the neighbouring countries.”

The movement did not stop. It rerouted. The road’s restriction reshaped the advantage, redistributing it. What Maiduguri lost in centrality, border towns gained in flexibility.

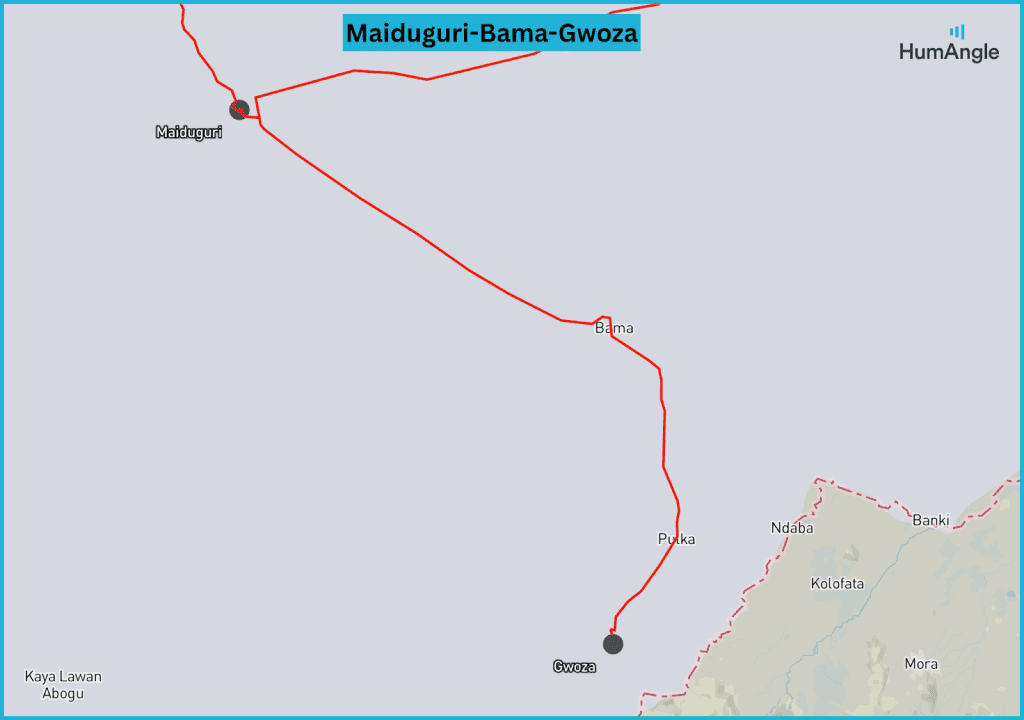

Elsewhere, the pattern repeated with variations. On the Maiduguri-Bama-Gwoza road, Muhammad Haruna remembers when nights were just nights. He began driving in 1981, commuting passengers to Bama, Gwoza, Pulka, Yola, and Mubi. “Driving to Bama took at least 40 minutes,” he recalls. “For Banki, Gwoza, and Kirawa, it was one hour and 30 minutes.” There were few checkpoints, he says. And these existed because of criminals. “And travelling to Mubi was three hours, while Yola was not more than five hours.” The roads were free, even at night. “On market days, as many as 200 fully loaded Gulf cars carried traders into these towns,” says Bamai Mustapha, Chairman of the Bama Park National Union of Road Transport Workers.

Here, too, the Boko Haram conflict affected the flow. Most of the roads became inaccessible, forcing drivers to take a long route passing through the forest into Dikwa, before reaching Bama, until it became totally impossible to travel. “After escaping abduction in 2015, I stopped driving,” Muhammad says. “I sold the car and went into trading.”

Some traders shifted focus to Yola, Muhammad says. They would import from Cameroon into Yola instead. “Others import to Jalingo.”

When calm slowly returned, the routes reopened, but with limited access. “In some of the towns, curfew starts early,” says Muhammad. “They close Bama and Konduga by 5 p.m.” “If you leave Maiduguri by 2 p.m. with Gwoza passengers, you must spend the night in Bama.”

Still, it is not totally safe. “There was a time we got stuck for about a week in Konduga, while going to Gwoza, waiting for military escorts,” Muhammad recalls.

There have been recurring attacks and abductions on these routes for about a decade. The Boko Haram terror group has turned to the kidnapping economy as one of its revenue windows. “The most dangerous route is between Gwoza and Limankara,” Muhammad reveals. “The terrorists would plant mines on the roads. You cannot follow the route without a military escort.”

Despite that, they must travel the route. “It leads into Cameroon. We often transport traders and goods imported from Cameroon through Banki, Kirawa, and Pulka into Maiduguri.” At least seven trucks filled with grains enter Maiduguri from Pulka daily, he says. “It used to be around 30.” “This is the same for Gwoza, Madagali, and other towns.”

The goods coming in, especially grains and animals, are transported onwards to Lagos in southwestern Nigeria and other cities, Bamai says. “They pass the Maiduguri-Damaturu road.”

The fish stopped coming

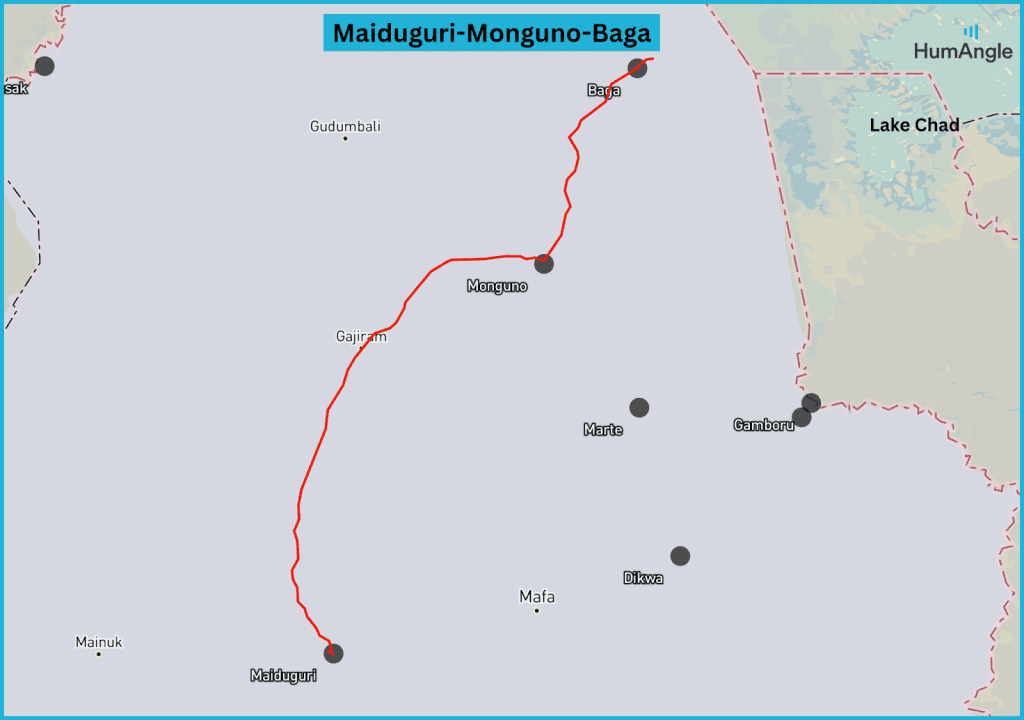

The story is the same on the Maiduguri-Baga-Monguno road. This is the backbone of Maiduguri’s fish trade. Audu Gambo began plying this route in 1990, transporting passengers, including traders and farmers, to Baga daily. “Driving to Baga used to take only two hours and 30 minutes,” the 54-year-old recalls. “There were few customs and immigration checkpoints, and the roads were good,” he adds. This enabled him to make a full trip twice, he says, until the conflict interrupted this frequency.

“Travelling has become difficult and restricted,” Audu says. “The entrance to Baga closes at 2 p.m.” So, they must leave Maiduguri as early as 8 a.m. “There are at least 30 checkpoints before reaching Baga,” he says. “Most of the drivers here are from Baga. Those of us from Maiduguri rarely travel the route.”

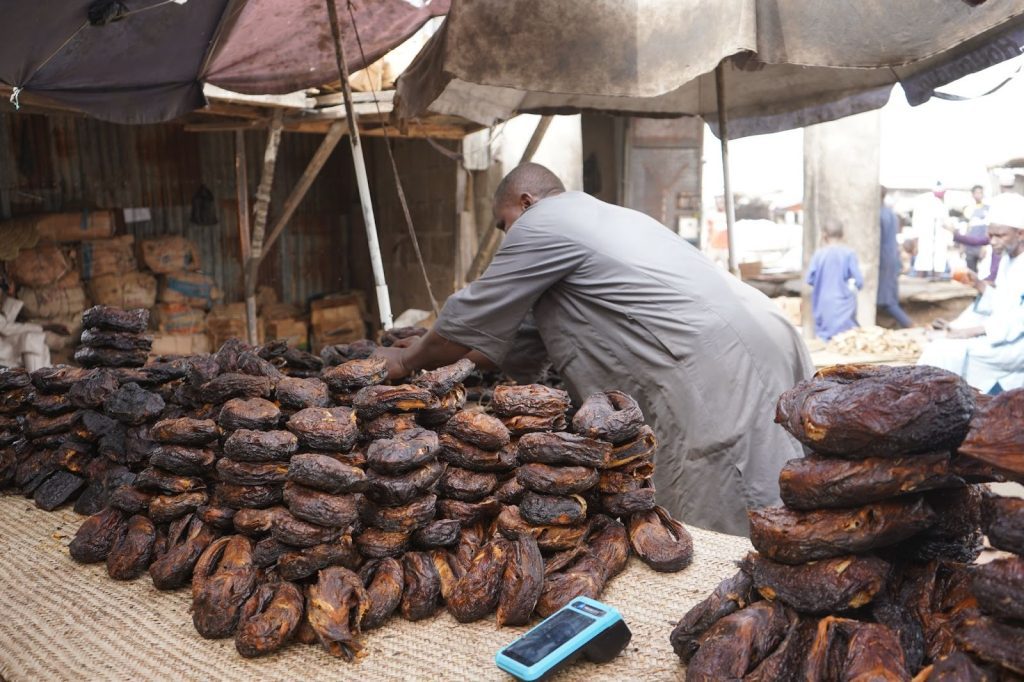

This affected the city’s source of protein. “I stopped going to Baga in 2017,” Abubakar Mustapha, a fish trader, recalls. It was 10 a.m. when I met him at his stall at the Baga Road Fish Market. “If it were before [the insurgency], we would have finished trading by this time,” he says. The influx of fish into the market has reduced. “They were cheaper and in abundance in the past. We used to offload at least five trucks of fish daily in the market.”

When the insurgency peaked, Abubakar recalls, it became one truck in days, until it became too risky to travel. The road became totally inaccessible.

Then the focus shifted to neighbouring countries. “We began importing from Cameroon, Chad, and Niger,” Abubakar recalls. “Fish from Cameroon and Chad are imported through the Maiduguri-Gamboru road. Those from Niger are brought in through Geidam in Yobe State,” and are transported through the Maiduguri-Damaturu road. “At least four trucks from these countries are offloaded daily,” he estimates. However, transporting to Maiduguri became costly. “Each cartoon costs 4,000 to import,” he says. So, traders relocated to Hadejia and Yola. “More than 50 per cent left.”

In the past two years, however, there has been cautious improvement. The market’s population has increased as previously closed roads are now accessible, Abubakar says. “Some traders have returned and they can now directly import from Baga and Monguno. Yesterday, we offloaded four vans. And the day before, it was three. It doesn’t go below or beyond this number.”

Yet, consignments from neighbouring countries make up the majority. “Fishers cannot freely access the water from the shores of Baga and Monguno,” he says. The shore there is one of the strongholds of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) terror group. To fish in the water, fishers must pay.

That afternoon, Yakubu Buba boarded a vehicle at the Muna Park back to Gamboru. His beans had been delivered. He has learned to accept delays as the new rules of the road. Still, he remembers it used to be free.

Yakubu Buba, a bean merchant, highlights the challenges faced by traders due to the Boko Haram conflict in northeastern Nigeria.

He describes how routes once busy with trade have become restricted, necessitating reliance on neighboring countries like Chad and Cameroon. Economic shifts occurred as Borno's towns adapted, redirecting trade channels and using military escorts for security. Routes like the Maiduguri-Baga-Monguno, critical for the fish trade, similarly faced disruptions, forcing traders to import from other countries. Gradually, some road access has improved, but security threats still necessitate caution and adaptation in trade routes.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter