In Search of a Living, Displaced Youth in Nigeria’s North East Face Deadly Violence

For young displaced persons like Mustapha Abubakar, a day’s farm work in northeastern Nigeria can end in abduction or death. Boko Haram insurgents routinely target farmers working in non-military protected areas, forcing families to sell their last possessions just to ransom their loved ones home.

Mustapha Abubakar was only eight years old when Boko Haram seized control of his village in northeastern Nigeria. In the months that followed, his community lived without safety, stability, and livelihood.

Before the insurgency, Mustapha’s childhood in Sharuri Tomsuwa, a remote community in Konduga Local Government Area of Borno State, was filled with joy. His family were successful farmers, living comfortably and caring well for him and his siblings.

“Our village was peaceful,” he recalled. “I would escort my father to his farm and play with my friends all day. We ate good food, and during Sallah, they bought us new clothes.”

Everything changed 12 years ago when Boko Haram besieged Sharuri Tomsuwa. Families were trapped, living in constant fear. There was nothing they could do, and even if they did, they risked severe punishment or even death.

“They [Boko Haram] killed many and prosecuted others violently as punishment for anyone caught trying to escape the village. They were preaching and admonishing us in the morning and afternoon,” Mustapha recounted. To a child, some of it seemed strangely thrilling: the chants, uniforms, motorbikes, and convoys. But his parents knew the danger all too well. One night, about a month into the occupation, when many fighters were away on an operation, his father, Abubakar, seized the chance.

These operations, often aimed at gathering supplies, kidnapping recruits, or enforcing control, sometimes left the village temporarily less guarded. For many families, such moments offered a fleeting opportunity, a dangerous window during which escape might be possible. Knowing the risks and aware that discovery could mean death, they acted swiftly.

It was during one of these rare moments that Mustapha’s family began their journey, leaving behind not only their home but the only life they had ever known. “My father woke us up in the middle of the night and led us out of the village. We walked day and night, looking for a safe place,” Mustapha recalled.

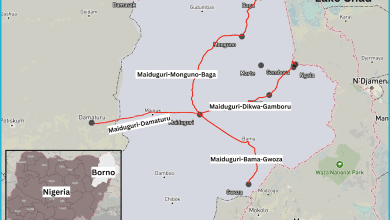

After navigating perilous paths out of their village, Mustapha’s family settled in Zannari, a neighbourhood in Maiduguri, about 37 kilometres away from Sharuri Tomsuwa. Like other displaced families, they found life in the city difficult. Poverty, hunger, and despair weighed heavily on them.

Mustapha’s father kept searching for a way out until tragedy struck. Six years after they had settled in Zannari, Abubakar was killed in a bomb blast that struck a mosque during Ramadan in 2021. They had hoped the community would offer safety; instead, it became another place scarred by violence.

Following his father’s death, Mustapha’s life became more difficult. He, along with his mother and six siblings, moved from one location to another, trying to find shelter, food, and peace. A year later, the family moved to Malari, a repatriated community in Konduga, Borno State. While they were still finding their foot in the new place, Mustapha’s paternal uncle was killed in a bombing attack in Malari, just one year after he lost his father in a similar incident. The cycle of grief seemed unending for Mustapha’s family, even as he grew into a teenager burdened with family responsibilities.

While his mother and siblings now live in Konduga, Mustapha is with another of his uncles in Dalori, a village along the Maiduguri – Bama road, at a residential community for displaced families. He visits his family sometimes and brings them glad tidings once in a while to support them.

His uncle, displaced also, tried his best to provide for Mustapha’s basic needs, even as his resources dwindled. But in a region where livelihood opportunities are scarce, Mustapha had no choice but to turn to farming, not on his family’s land, which they no longer had access to, but on plots owned by others.

In this new life, displaced people like Mustapha are facing discrimination over resource distribution and are often treated as outsiders. The accessible farmlands in the areas are not theirs. HumAngle found out that many displaced persons have been repatriated to areas that serve as LGA headquarters or satellite villages under tightly monitored and bounded by strict security perimeters.

Going beyond these zones, especially into bushlands to farm, means risking one’s life. But poverty pushes many, including Mustapha, to take that chance.

During every farming cycle, Mustapha, along with other displaced youths, usually walk long distances to do manual labour. They are paid ₦3,000 daily. It was during one of these trips in July, while working on a farm near Kambari, that he and seven others were abducted by suspected Boko Haram terrorists.

Mustapha told HumAngle that his captors had disguised themselves as women during the incident.

“They wore hijab and hid their faces with niqab (a veil worn by some Muslim women in public, covering all of the face apart from the eyes). The group was armed with rifles and drove on motorbikes,” he recounted. “When they approached us, we thought it was women who wanted to ask for directions or something else, like help. Suddenly, they beckoned me and the other three who were working on the farm. Then they took out their rifles, hidden under the hijab.”

As Mustapha and his three colleagues tried to comprehend what was happening, the captors whistled towards the north. Within moments, five motorbikes, each carrying two people, arrived. The armed men flogged and tied the youths up before taking them deep into the bush, where they were kept in a wooden hut under constant threat.

Mustapha and the other three were later joined by four additional captives seized from nearby farmlands, making a total of eight men. That was the first day of what would become two harrowing weeks in captivity.

According to Mustapha, the men who abducted him looked rough and unkempt. Their hair and beards were overgrown and bushy, and they gave off a strong stench, as though they had not bathed in years. Their appearance alone was frightening, he recounted, but it was their behaviour that truly terrified him. They were harsh, aggressive, and violent, often beating captives with the butts of their guns and threatening to kill anyone who disobeyed.

One of the captives was killed in front of Mustapha and the others.

“We were terrified we would be next,” he recounted. “The living conditions were simply inhumane; they gave us white rice with salt and no soup. We were tied up all the time.”

Three days after their abduction, the captors demanded ₦1.5 million as ransom for each captive, including Mustapha. They later reduced it to ₦1 million. Mustapha was released two weeks later after his family scraped together the ransom. His sisters and uncle sold family belongings and even a plot of land. They borrowed money from neighbours, some of whom contributed in small amounts to help save him.

In addition to the ₦1.5 million ransom, Mustapha’s abductors demanded ₦15,000 worth of Airtel airtime, two packets of spaghetti, 15 kilograms of rice, and 20 litres of cooking oil.

The ransom was delivered by an elderly woman, Kaltum, who was nominated by the community, following the abductors’ instructions that it should be brought by an older woman. Kaltume, known for her calm demeanour and familiarity with the surrounding area, was handed the cash and took the risky journey alone into the bush to ensure Mustapha’s safe return.

Though free, 20-year-old Mustapha lives with fear and trauma. He has abandoned farming. “It’s not worth dying for ₦3,000,” he told HumAngle. Now, he spends most of his days in idleness.

His mother remains in Konduga with his younger siblings, while Mustapha continues to live in Dalori with his uncle. He wants a safer life, a fresh start. “If I can get support to start a small business, maybe I won’t have to go to the bush again,” he said, his voice filled with quiet desperation.

Although it’s not news that abductions were occurring in these communities, residents say that the frequency of abduction cases this season is scary, and this has pushed displaced persons and their host communities into incessant chaos.

HumAngle observed that the security protection services, provided by the Nigerian military and members of the Civilian Joint Task Force stationed at a few checkpoints, are insufficient to cover the vast farmlands cultivated by local farmers. As a result, many residents like Mustapha fall victim to abduction while working on the farmlands.

Locals who spoke to HumAngle lamented the lack of government response to the frequent abductions and said there is no support in negotiating the release of their loved ones held captive.

“You can’t blame us for taking the risk. There’s no other way to survive,” Mustapha added.

Mustapha Abubakar's life dramatically changed when Boko Haram took control of his village in northeastern Nigeria, disrupting his family's once peaceful farming existence. Seeking safety, his family fled to Maiduguri, but continued to face hardships. Tragedy struck when Mustapha's father was killed in a bomb blast, leaving the family in dire straits.

Now living with his uncle, Mustapha struggled for a livelihood and opted for farming on unfamiliar lands, risking abduction by Boko Haram. He was kidnapped during a farming trip, alongside others, and faced brutal conditions before his family could gather ransom for his release. Despite his freedom, Mustapha is haunted by his ordeal and seeks a safer life, hoping to start a small business to escape the dangers of farming in a conflict zone. The community remains plagued by frequent abductions amidst insufficient security and government support.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter