In Nigeria’s Shiroro Town, Terrorists’ Incursions on Power Plant Threaten National Grid (2)

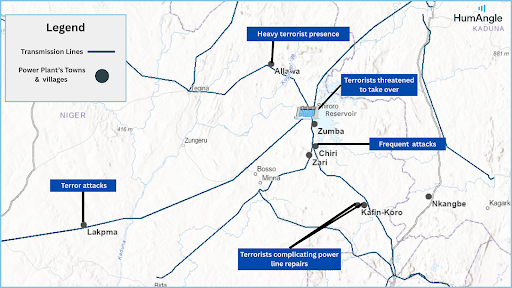

Boko Haram elements are thriving in the Allawa forest; there are also rural terrorists and kidnappers. They attack towers when there are no more cattle to rustle and no humans to kidnap. They vandalise the towers so that they can sell the cables elsewhere.

When a national treasure was planted on the shore of Shiroro in Niger State, North-central Nigeria, the locals heaved a sigh of relief. The Shiroro Hydroelectric Power Plant paved the way for the satellite town, putting it on the national stage. The locals raised their expectations, believing that with such an establishment, infrastructural developments would naturally follow.

They were wrong.

As Boko Haram hoisted its flag in Niger State, insurgent fighters began to display an incursion against the people and the local authorities of the state. They had formed a parallel government physically stationed on the fringes of the Allawa forest in Shiroro. Led by Mallam Sadiqu, Boko Haram domesticated the display of insurgency.

The Boko Haram playbook led Sadiqu to orchestrate the destruction of public assets to set those in power off balance. They started by attacking those securing lives and properties, ambushing soldiers to death and killing police officers indiscriminately. As the attacks intensified against security agents, soldiers stationed in the hard-to-reach areas of Shiroro withdrew, and the police deserted the areas, leaving local vigilantes with limited resources behind.

The Shiroro Power Station, a hydroelectric marvel on the Kaduna River in Niger State and one of Nigeria’s national treasures has been a beacon of light since 1990, providing electricity to over 404,000 homes across 17 northern states.

Once a peaceful civilian setting and the proud host of the power plant, Shiroro has been transformed into a terrorist haven, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake. The infiltration of Boko Haram elements in 2020 unleashed a fresh trove of terror as the group’s radical ideologies took root, preaching against secular education, enforcing child marriage, and recruiting vulnerable boys into their deadly ranks.

Despite the government’s vows to eradicate the terrorist menace, the group has not only persisted but has also grown in strength, daring to attack the Shiroro Power Plant. When terrorists invaded the power plant in 2024, they sent 17 northern states into darkness, worsening existing economic hardship. The federal government’s subsequent ₦9 billion restoration effort only underscores the terrorists’ sinister triumph.

The brazen assault, along with others like it, appears to be advancing the terrorists’ anti-state agenda, leaving Nigerians to question whether their government can truly safeguard national treasures and ensure public safety.

The paradox of proximity

Before terrorists got a grip on the power plants, villagers around the hydroelectric station in Shiroro lamented the lack of electricity. Despite hosting the 330kv power station, these communities suffered a total blackout for years. Residents of villages like Zumba, Chiri, Nkangbe, and Zari said they had to forfeit integral parts of their ancestral land to the power plant, hoping it would bring light and prosperity.

“We were resettled to today’s Zumba by Tonor (the company that managed the Shiroro Power Plant in the ‘70s),” Ahmed Kilishi, a Zumba community leader, told HumAngle. “Our people were moved from the old Zumba, where they built the power station, to the new Zumba; our farms and homes were taken over by the power station.”

“Despite hosting a national treasure, our people reap no benefits. We endure erratic electricity, never enjoying 24-hour power. In the entire local government, not a single community has uninterrupted electricity,” Yusuf said. He noted that Erena is the lone exception, receiving a trickle of benefits, while the rest of Shiroro remains largely in darkness, with some places experiencing only three to four hours of electricity daily.

“Erena and Allawa were the only communities that enjoyed electricity. In Allawa, it wasn’t stable because it took time to fix it when the cables were vandalised due to a lack of access roads. Although these communities are not far from the dam, they lack security, basic amenities, and even electricity,” Rabiu Iliyasu, a resident, noted.

When HumAngle arrived in Kuta at 9:30 a.m. on a sunny Saturday in March, there was no electricity until five hours later. At exactly 5:47 p.m., the light went out again, lasting only about three hours.

“If you are here at night, it feels like you could extend your hands to the illumination over there [the camp], but it is dark here. Why are we treated differently?” Kilishi asked.

While en route to Zumba from Kuta via Ebbe, HumAngle noticed several motorcycles loaded with ice from Zumba heading to Kuta. Over 15 motorcycles were counted. However, upon arriving at the community, there was no electricity.

Locals told HumAngle that the ice was from an estate near the power station. Due to the lack of electricity and the hot weather, villagers rely on the ice to cool their drinks.

When we reached the junction connecting the community, the power station, and the estate, motorcycles were parked, waiting for the ice to be delivered. There were visible signs of electricity; the bulbs hanging on nearby walls were on.

The estate, Chastmen Camp, serves as a residential unit for the power station’s management staff.

“Every ice block from Zumba is from the Chastmen Camp. The wife of the Chief Operating Officer sells them at the junction,” alleged Kilishi. “A big brick of ice goes for ₦700, while smaller ones go for ₦200. If we were selling ice, the price would drop so that people could afford it.”

Villagers expressed deep frustration over the prolonged blackout, which they attributed to a reported shortage of transformers. While local communities endure darkness, Kilishi claims that residents of the estate enjoy uninterrupted power, supported by 18 transformers, numerous air conditioners, and even 12 cold rooms housed within a single building. HumAngle could not independently confirm these claims.

“We have written to them, but nothing has been done. Look at our neighbouring communities here, where the cables pass to other places, but there is no light. It is very untrue to say Zumba enjoys stable electricity. Since the commencement of this year’s Ramadan fasting, we have been in a blackout,” Kilishi said.

CSR out of reach

Yusuf’s voice dripped with disappointment as he recounted the broken promises of those in power. Since the dam’s construction encroached on their land, the power plant authorities had pledged a housing estate to the Galadiman Kogo community as a gesture of goodwill. But the project remains a mirage, a haunting reminder of unfulfilled expectations.

“We expect that with an asset like this in our communities and, by extension, local government, we should enjoy road networks, hospitals, veterinary clinics, and other basic amenities, but there are none,” he complained.

The situation is not different in Zumba, another community in the Shiroro area. When HumAngle visited the location in March of this year, barely two kilometres from the dam and power plant, we observed the deplorable state of the road network leading to the community. The road is adorned with unique patterns of potholes, making it difficult to miss hitting one.

“We have not benefited from this aspect of CSR from the power company,” Kilishi said. “Before now, even bicycles found it difficult to ply our roads. We were able to tackle that problem through our association.”

Usually, host communities of significant assets or companies benefit from corporate social responsibility initiatives that enhance infrastructure and increase employment opportunities. Communities in Shiroro, however, see little evidence of such investments, raising questions about why they have been left behind.

The company responsible for the Shiroro hydropower station is North-South Power. On its website, it boasts of playing a critical part in the development of its host communities through its foundation. However, observations by HumAngle and accounts from residents reveal a striking contrast.

Road to hell

The situation has only worsened over time. In addition to the power blackout, communities around Shiroro lack other basic infrastructure, including roads. “We don’t have access to good roads in the Lapkma axis,” Dangana Yusuf, a displaced resident of the Chukuba community, told HumAngle. “The present governor is trying to fix the Shiroro to Erena road, but there are no road networks in these communities that extend to the power station.”

The only relatively reliable route is the road from Minna to Shiroro Dam and Zungeru Dam, a reminder of the region’s neglect.

“From the dam to the eight wards [in the area], there is no single tarred road leading to these communities,” Iliyasu said. “From Pandogari, some culverts and bridges connect us with Kuta, which were built during Shehu Shagari’s administration, but the roads are not tarred.

“During Buhari’s tenure, they started constructing the roads, but the security operatives dismissed the workers when they were attacked by terrorists. That halted the work, and it has enabled these terrorists to carry out heinous crimes with minimal response.”

In communities like Zumba and Bassa, among others, residents have complained about North South Power, the company responsible for the power plant, and the lack of corporate social responsibility initiatives in areas such as health, education, and the provision of basic amenities.

“Zumba dispensary is not only painful but disgraceful. It is part of the corporate social responsibility that we ought to enjoy from the hydroelectric power station. Today, there is nothing like that,” Kilishi said. “Talking about schools, those abandoned buildings were constructed by a mining company years ago. We have written to the hydroelectric power station on several occasions to come to our aid, but they haven’t. In the area of scholarships, no villager has been given scholarships by the power station.”

The dire lack of critical infrastructure, like access roads, has exacerbated the worsening security situation. Many communities, including Bassa, Allawa, Chukuba, and Kurebe, are almost entirely cut off from security intervention due to impassable roads.

Security operatives responding to attacks struggle to navigate these rough terrains, allowing terrorists to operate with impunity, locals told HumAngle. This, according to them, has left residents at the mercy of armed terrorist groups who invade villages, loot property, plant landmines, and abduct residents with little or no resistance.

On-site sources say the proximity of this national asset [transmission towers] to their communities and the unavailability of access roads leading to the locations of towers vandalised by terrorist elements have significantly contributed to escalating the insecurity within the region. HumAngle observed that beyond security concerns, the lack of accessible roads has also hindered the swift repair of this critical infrastructure tucked within these affected communities.

The vandalisation of transmission cables by terrorists has, on numerous occasions, plunged many parts of the country into darkness, particularly the northern states. With no roads, repairs can result in significant delays reaching affected sites, prolonging power outages and worsening economic disruptions.

The infrastructural neglect has not only emboldened criminal elements like Dogo Gide to perpetrate heinous acts but has also left vital national assets vulnerable to repeated sabotage by terrorists. “Dogo Gide is the one behind the vandalisation of the transmission towers/lines. They attacked the towers so that they could get access to the Kuta and Gwada areas. But their efforts have been abortive,” Yusuf revealed.

Dogo is a notorious terrorist leader who was responsible for the abduction of more than 100 schoolchildren from the Federal Government College, Birnin Yauri, Northwest Nigeria, in June 2021.

Abdullahi Yerima, a former chairman of the local government and a retired senior police officer, told HumAngle that he had confronted the terrorists in 2013, at the early stage of the insecurity. He revealed that the location of the hydropower station is a vulnerable point of attack.

Yerima noted that the terrorists belong to different groups and have established camps across the affected communities. “Between Galadiman Kogo and Shiroro is less than two kilometres,” he said.

“They are of different groups. There are Boko Haram between Allawa and Kurebe; there are also rural terrorists and kidnappers. These terrorists attack towers. And they do so when there are no more cattle to rustle and no humans to kidnap. That is when they vandalise the towers so that they can sell the cables elsewhere,” Yerima claimed.

To chart a path for peace, he advised that all mining activities in the Shiroro Local Government Area must be suspended and a military camp established between the Allawa and Kurebe communities, which will enable displaced residents to return to their communities and rebuild their lives.

Terror in the dark

As displayed in Nigeria’s northeastern region, terrorists invoke darkness on volatile communities to gain control, leaving authorities with no clue of curbing anti-state activities in areas like Shiroro. In the states of Borno and Yobe, Boko Haram terrorists launched multiple attacks on power plants, vandalising towers to cause darkness.

Since at least 2020, repeated cases of terrorist vandalisation of the hydroelectric power plants plunged communities in Borno and Yobe into total darkness, crippling the local economy of the states and business activities. In September 2024, for instance, Boko Haram vandals destroyed the Gombe-Damaturu-Maiduguri transmission line just three months after repairs by the Transmission Company of Nigeria, throwing hundreds of communities in Yobe and Borno into utter darkness. In February of that same year, the insurgents vandalised two 330 KVA power transmission towers in the state, using improvised explosive devices to blow up the facilities supplying electricity from Gombe to Yobe and Borno states.

Before then, in 2023, an official of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps was killed when terrorists bombed three power transmission towers along the Maiduguri-Damaturu road. Similar preceding attacks had thrown communities in the North East into darkness. In mid-January 2021, a Boko Haram attack on several high-tension towers resulted in a year-long blackout. The towers were restored in April 2021, only to be sabotaged again, curtailing the brief respite enjoyed by the residents.

HumAngle documented the trail of devastation left in the wake of Boko Haram’s rampage through Adamawa’s border towns, including Michika and Madagali, between 2014 and 2015. The militant group’s brutal assault on innocent lives transformed a once-thriving tourist hub, rich in cultural heritage, into a no-go zone.

In a calculated move to cripple the local economy, Boko Haram insurgents deployed improvised explosives to destroy high-tension electricity installations in September 2014. This sinister act severed the towns’ connection to the national grid, plunging Michika and Madagali into darkness.

Many years later, the shadows of that fateful day lingered. Many towns in Adamawa remained shrouded in perpetual darkness as businesses struggled to stay afloat. As at 2023 when HumAngle documented the story, the crippling cost of relying on generators forced some entrepreneurs to shut down their operations, leaving them jobless and without a lifeline.

The Boko Haram terrorists rooted in Shiroro operate in the same fashion as their counterparts in Borno. In a desperate step to ground the local economy of the people, they destroyed the hydroelectric power station in the area, invoking dangerous darkness and setting civilians off balance.

It is the same situation that is playing out in Niger State.

When HumAngle visited Shiroro, we observed that while security agents were stationed at the power plant, the host communities were unprotected, leaving the locals vulnerable to terrorist attacks.

On several occasions, military officers assigned to protect the communities have had to vacate the place for more secure garrison locations. Notably, we found no military barracks near the power plants that could allow for a swift response to attacks. Instead, we saw vast and empty lands from Minna to Gwada and Zumba, dotted only with scanty hamlets.

However, we saw two security vehicles at the exit point towards Shiroro, located in front of the Dana Pharmaceutical Company, a prominent Nigerian pharmaceutical company, in Maitumbi. Locals told HumAngle that there are security agents in Erena, a few kilometres away from the power plant, but they rarely respond to attacks within the communities.

This is the second of the three-part series investigation on the human costs of the infiltration of Boko Haram elements in Niger state. Read the first part here.

The Shiroro Hydroelectric Power Plant in Niger State, Nigeria, was expected to bring development to local communities but failed as Boko Haram established a strong presence, attacking infrastructure and security forces.

The militants, led by Mallam Sadiqu, escalated violence, forcing a military withdrawal and leaving locals vulnerable. Despite its strategic importance, the plant failed to provide electricity to nearby communities, leading to economic strain and dissatisfaction. Additionally, persistent infrastructure neglect, lack of corporate social responsibility, and a deteriorating security situation have left these regions in continuous darkness, exacerbating vulnerabilities.

The situation highlights a paradox of proximity, where a region rich in resources and potential is crippled by insurgency and infrastructural neglect, making it vulnerable to further terrorist attacks.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter