In Nigeria’s Borno State, The Displaced Trade Shelter for Life

Displaced and repatriated families in northeastern Nigeria are facing new layers of suffering. In Dalori, returnees are being abducted from farmlands and forced to raise ransom or risk execution, while in Muna Kumburi, families are dismantling and selling their makeshift shelters to feed themselves, fund farming activities, or flee the worsening conditions.

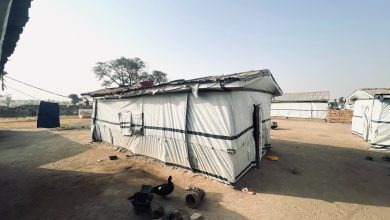

At the Muna Kumburi camp along Dikwa Road in Maiduguri, northeastern Nigeria, displaced families are taking desperate steps to survive.

With the provision of humanitarian aid having been ceased for over three years and growing insecurity keeping them from farming freely, dozens of internally displaced people (IDPs) have begun dismantling and selling the very shelters meant to keep them safe.

“We have no choice,” Malum Aisami, the camp chairperson, told HumAngle. “People are in such a desperate situation that they sell their shelter and travel using the money.”

The makeshift tents, constructed from wood, tarpaulin, and zinc sheets, are sold for ₦40,000 to ₦50,000. They use the money to feed their families, buy seeds, cultivate lands in remote areas, or attempt to resettle in safer areas.

When HumAngle visited the camp on July 24, many spaces where shelters once stood now lay bare, marked by upturned soil and abandoned frames.

While some moved into nearby host communities after selling their shelter, other families squeezed into overcrowded shelters with relatives in the camp. Many travelled to remote bush areas to work on farmlands, and some relocated entirely to farming settlements for the duration of the rainy season–a common practice among families in the region seeking seasonal agricultural income.

“I sold it so that I can use the money to go and buy seeds and feed myself on the farm,” Baisa Modu said, pointing to the plot where his shelter used to be.

Camp residents say the situation worsened when the state government began constructing buildings in parts of the camp, displacing even more families within an already overcrowded space. Some residents relocated to nearby host communities, but many remain in desperation for a good life.

“So far, we’ve recorded over 50 households who dismantled and sold their shelters and moved on. Even me, I sold one of mine. There is hunger, and we cannot go to a farm in peace. There is insecurity and abduction on a daily basis,” Aisami said.

In February this year, several residents of the same camp were abducted while fetching firewood in the bush. Their families were forced to launch crowdfunding efforts, scraping together ₦300,000 in a desperate attempt to pay the ransom demanded.

Now, as hunger worsens and with risks rising, selling shelters has become a survival strategy, even if it means sleeping in the open or starting over in a new place.

Despite their depressing conditions, over 200 households were also forced to vacate parts of the Muna Kumburi camp last month to make way for a government construction project. The development, which affected nearly half of the camp’s area, rendered many families homeless, pushing them to seek refuge in surrounding host communities.

The camp, which accommodates over 3,000 individuals across more than 600 households, is now experiencing one of its most severe humanitarian crises to date. The perios is marked by food shortages, insecurity, and the gradual disappearance of what little shelter remains.

HumAngle reached out to both the Borno State Police Command and the State Government spokesperson for comments regarding the increasing cases of abductions targeting returnees in Dalori and the humanitarian distress in Muna Kumburi. At the time of filing this report, no official response had been received.

Abduction cases are rising

After Boko Haram members abducted and killed her husband in 2019, Maryam Indi fled her hometown of Goniri Kadau in Konduga local government of Borno State.

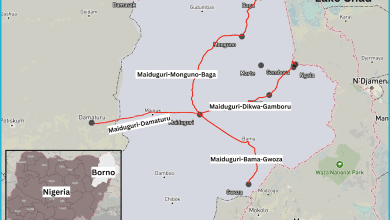

Accompanied by her family, she fled to Maiduguri, the capital city, settling at the Kawar Maila camp for displaced people. She lived there for about six years until the government shut down the camp in 2023 and repatriated her and all other occupants to the 1,000 Housing Units situated at Dalori village along the Bama–Maiduguri road.

She now lives there with her six children, she says, and life has only grown more difficult and unbearable since their return.

The 55-year-old worked as a farm labourer but stopped this year when suspected Boko Haram members began kidnapping residents who were going to the fields.

Her father-in-law, Ba Modu, was taken just five days before, while returning from the farm in Lawanti, a remote village in Konduga. He was one of eight people abducted from the community when HumAngle visited on July 25.

“The kidnappers demanded ₦1 million per person, but we couldn’t raise the money,” she said.

The abductors warned that Ba Modu would be killed in a week if the ransom was not paid. Maryam says this isn’t the first time their family has suffered such an ordeal.

“We have had three other cases of abduction in our family since we were repatriated to this estate. We paid ₦400,000 to free them,” she recalled.

But now, there is nothing left to give. And the process to raise the money is nearly impossible for many families.

“We used to go around the neighbourhood collecting donations from people, like ₦200 here, ₦500 there. But this time, we couldn’t raise anything. Everyone is suffering,” Maryam told HumAngle.

Maryam now begs in the markets across Maiduguri to feed her children. She said her daughter had recently narrowly escaped an attempted kidnapping while fetching firewood. Her son, who was with her, became sick with shock after witnessing the incident.

“We are scared. We can’t even go outside without fear. We are just surviving on begging and prayers,” she said.

Women like Maryam now bear the brunt of farming-related risks. While farming is often considered a male-dominated occupation in the region, the current insecurity has pushed many men into hiding, leaving women to farm in distant and dangerous areas.

“Our men are afraid to go. If they go, they’re targeted more. So we, the women, take the risk,” Maryam said.

Since 2021, the Borno State government has implemented a phased closure of displacement camps across Maiduguri, relocating IDPs to newly built housing units in their ancestral communities or nearby towns. The policy was premised on restoring dignity, reviving local economies, and reducing long-term aid dependency.

As part of the exercise, at least ten informal camps in Maiduguri have been shut down. The most recent was the closure of Muna IDP camp in May 2025, during which the state governor, Babagana Umara Zulum, oversaw the relocation of 6,000 displaced families.

The government said the decision was driven by rising issues of crime, drug abuse, and child exploitation within the camp. However, the transition has deepened the humanitarian burden for many, particularly those unable to relocate or access livelihoods.

For many returnees, the promise of stability and improved living conditions remains unfulfilled.

Yakaru Abbagana, 30, another returnee, fled Shettimari in Konduga and lived at the same camp with Maryam before being relocated to the Dalori estate. She now lives with her husband and eight children in what was meant to be a fresh start.

“I used to be a farmer. Now, my children and I beg for survival. Sometimes my children and I go three days without food,” she told HumAngle in a faint voice.

When HumAngle visited her for an interview, her brother, Mammadu, had been abducted ten days before while working as a farm labourer in Lawanti. As with Ba Modu, the captors are demanding ₦1 million. The family cannot raise it; their only asset is the house gifted to them through the resettlement scheme.

“We told them we don’t have that money. They told us to sell our house for his release. But if we do that, we’ll have no shelter. Nothing,” she said.

Yakaru’s family had faced abductions in the past, too.

“Two of my uncle’s children were kidnapped last year. We paid ₦500,000 each to get them out. But now, we have nothing. Only this house the government gave us,” she said.

The uncertainty and fear have left many families choosing between starvation and the risk of death. “We are just begging. That’s our only means now,” Yakaru said.

On July 25, Nagari Bunu’s younger brother, Mustapha Bukar, 20, was abducted while farming. Ngari told HumAngle that, in two days, their family managed to raise ₦900,000 out of the ₦1 million ransom through community donations.

He added that their father had considered selling their tent to raise the money, but community members helped. “People came together to help. They said we shouldn’t sell the house,” Nagari said.

Mustapha was abducted alongside others, but he remains the only one in captivity as others have paid and regained their freedom. The captors did not set a deadline but made it clear that Mustapha would not be released until the full ransom was paid.

Muhammed Usman, 30, is a community representative of the repatriated families from Kawar Maila camp, overseeing about 400 households now living in Dalori. His account reflects a community on the verge of collapse.

“This year alone, more than ten people have been abducted from our community while trying to farm. At least eight are still in captivity. The total ransom demanded is over ten million naira,” Muhammed said.

He explains that farming is not only a livelihood but the only lifeline left for many. Yet the farmlands surrounding Dalori and other nearby farming areas have become hunting grounds for Boko Haram.

Each time their community members are abducted, they resort to crowdfunding as authorities or organisations do not support them in the process. Muhammad says they do it alone year in year-round.

“We rely on neighbours to contribute what they can to rescue victims. But now, even that system is failing. We are all empty,” he told HumAngle.

According to locals interviewed by HumAngle, security presence is patchy. Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) members are stationed in some areas, but vast stretches of farmland remain unprotected.

“The government helps by giving us these houses. But they don’t help when our people are kidnapped. No food, no aid, no security. We are on our own,” Muhammad said.

The displaced communities continue to appeal for urgent government intervention to address their growing insecurity, hunger, and lack of support in resettlement areas

At Muna Kumburi camp in Maiduguri, Nigeria, displaced families are dismantling and selling their shelters to survive, fueled by prolonged cessation of humanitarian aid and insecurity preventing farming.

As shelters are sold for around ₦40,000 to ₦50,000, families use the proceeds for food, seeds, or relocation to safer areas, despite harsh conditions with minimal shelter. The camp's population grapples with governmental displacement from new constructions, rising abductions, and significant humanitarian crises, exacerbated by inadequate governmental support and insecurity.

Abductions are rampant in the region, with Boko Haram targeting farming residents, demanding ransoms that impoverished families find challenging to raise. Individuals like Maryam Indi and Yakaru Abbagana face repeated abductions, forcing them into begging, facing starvation, and risking dangerous farming.

The government’s phasing out of displacement camps aimed to restore dignity and economic activity, but the resultant instability and lack of aid further plunge families into despair, relying on community crowdfunding for ransoms amidst unreliable security support.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter