In Kano, Criminal Networks Evading Surveillance Are Terrorising Some Villages

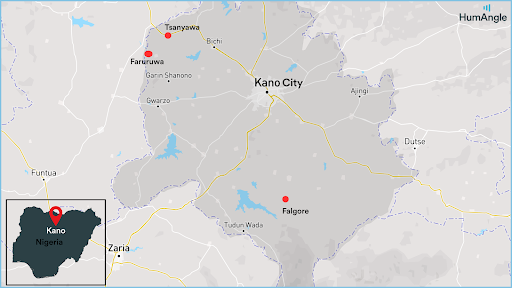

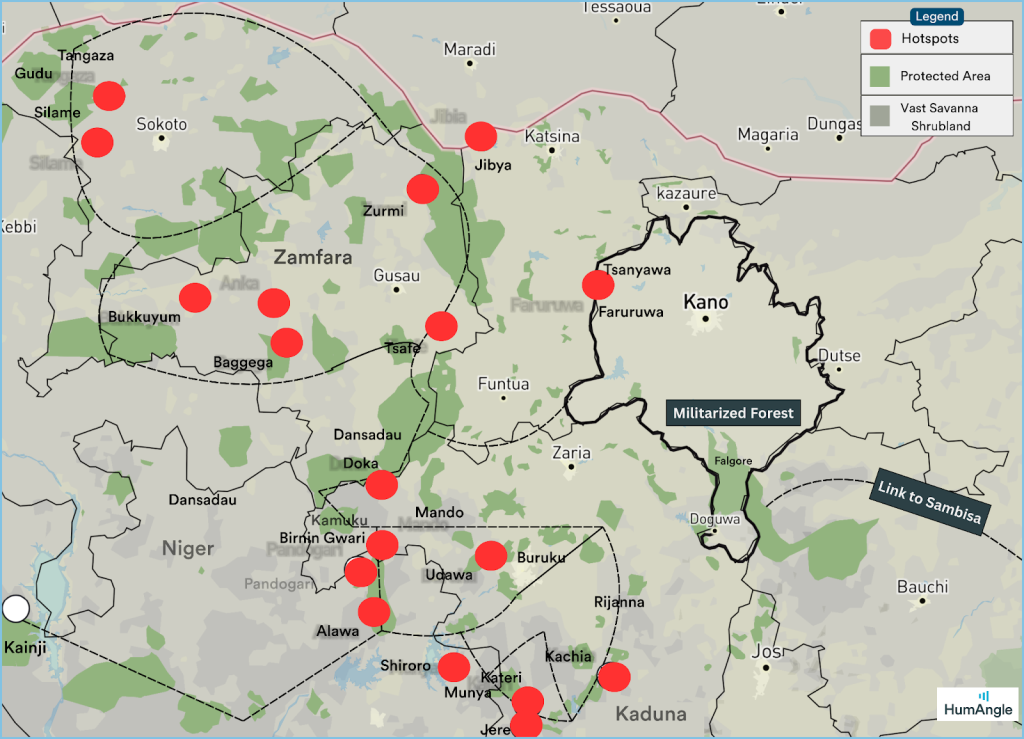

In northwestern Nigeria, Kano is used as a transport hub for terrorists evading arrests. The state’s security architecture and geographic location have contributed to low levels of terrorism. However, for more than three years now, abductions and killings have been recorded in places like Shanono and Tsanyawa.

Musbahu Shanono used to love the journey home. There was something about that drive from Lagos to Shanono, something about the way the roads gave him a nostalgic feeling after he passed through Kaduna; those familiar roads filled with the scent of dust and leaves.

He would always arrive just before sunset, when neighbours and friends were about to gather for Maghrib, an Islamic evening prayer, and children were racing beside cars, shouting greetings that express joy. But these days, he arrives in silence under the cover of night because kidnappers have started abducting people in his village, and there are criminal informants everywhere.

“Now I only come at night,” he said. “No one should know I’m around. Not even my friends. Not until I’m sure it’s safe.”

During the recent Eid al-Fitr festivities, neighbours were surprised to see Musbahu walking around in the morning. When asked when he arrived, he told them he came at midnight. There was no announcement, no greetings at the junction; just a quiet return.

Faruruwa, his childhood home, sits in Shanono, a quiet village on the outskirts of Kano State, North West Nigeria. The town used to be filled with soft and gentle rural life: early morning prayers, people under shade, and weekly markets.

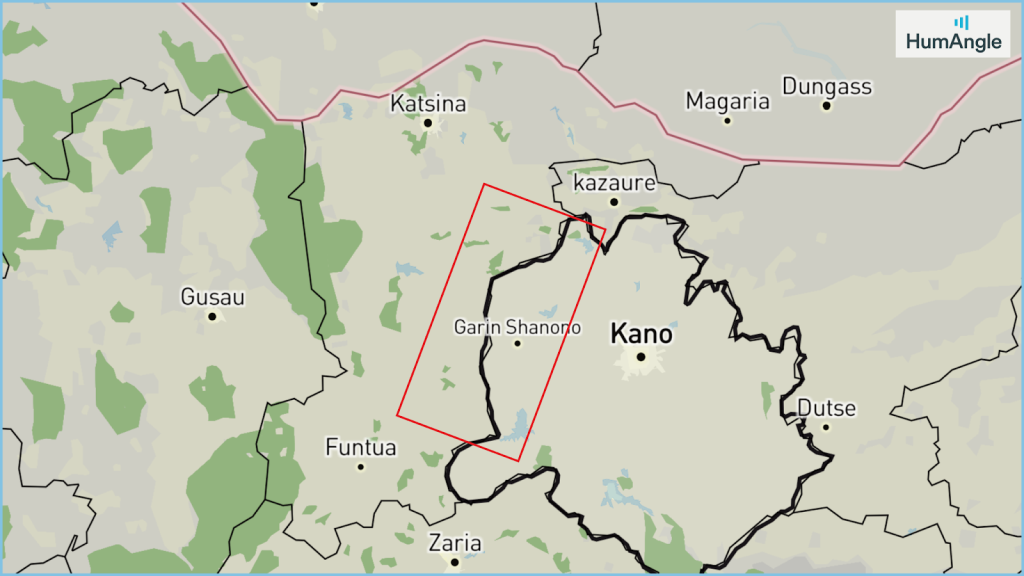

But now, an unease has seeped into the soil. The road to Shanono, from Alajawa to Goron Dutse, is no longer what it used to be. The village and its neighbour, Tsanyawa, lie close to the border with terror-laden Katsina State, a boundary that once meant very little. They shared language, marriages, and markets, making the line feel imaginary. That vast and porous border has now become a crack being exploited by terrorists.

For more than three years, men with guns—many locals say they are from Katsina—have been crossing into the edges of Shanono and Tsanyawa in Kano to operate, abduct, and kill.

“Last year, they took a man, our neighbour,” Musbahu recalled. “All because someone heard he paid for Hajj the previous week.”

The informants interpreted his ability to afford the Islamic pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia as a sign of wealth. Musbahu said they suspect someone in the village is feeding information to the kidnappers. This has made locals wary of one another, eroding generations of trust within the community.

Musbahu added that victims of kidnapping had to pay ransom, but even that doesn’t guarantee their lives. “Sometimes, they come back. Sometimes, they don’t,” he said.

He told of a man, Alhaji Ahmadu, who was abducted in 2022 in Tsaure. The abductors requested a hefty sum, but his family paid only what they could afford. He returned, broken but breathing. But they came again for one wealthy herder, Abdullahi Mai Rakumi. Then, they returned for his son. This time, there was no return for the boy; he was killed.

On a Thursday evening in April, they came again. Musbahu’s mother was at a wedding in Faruruwa, surrounded by family and laughter, when the sound of gunfire fractured the evening. The kidnappers arrived, and two people were killed. Two more were shot as they ran. They sustained injuries and were taken to the hospital.

“She called me,” Musbahu said, his voice tightening. “She was shaking. I called someone else from the village. He said, ‘Yes, they came.’ Two dead. Many wounded.”

The Shanono Local Government Area (LGA) chairperson, Abubakar Barau, confirmed the incident. He said apart from the two killed and those wounded, two persons were also abducted during the attack.

The Kano Command Police Public Relations Officer, Abdullahi Kiyawa, also verified the incident and promised to share more information after investigations.

In Faruruwa, people now live by the rhythm of fear. The night is no longer a time for rest. It is a time of silence, watching, and hoping not to be noticed.

Terror across the border

Kano is known for its calm. Its geographical landscape, which makes it distant from any large forest area, has made it more secure. The streets, even at their busiest, carry a kind of dignity. But peace, like glass, shatters. Security analyst Balarabe Ismail says the actual danger is not noise but silence.

“The threat of insecurity manifests every day, but we ignore it. By the time you see it, it’s already here,” he lamented.

Since the early 2010s, Nigeria has witnessed a surge in mass kidnappings, with incidents ranging from the notorious Chibok school girls abduction to recent events like the Kuriga incident. In northwestern Nigeria, the situation has escalated, turning the region into one of the most dangerous parts of the country as terrorists exploit ungoverned territories, primarily around vast forest reserves, to carry out abductions of various targets, including farmers, travellers, officials, and school children, in alarming numbers.

In 2024 alone, over 500 people were kidnapped in mass abductions across northern Nigeria, most of these in communities near expansive wilderness areas, especially in the northwestern states. As a rich bed of terrorism, the northwestern region has a history of ancestral rivalry between the nomadic herders and local farming communities. These lasting grievances are driven by poverty, land scarcity, and environmental pressures.

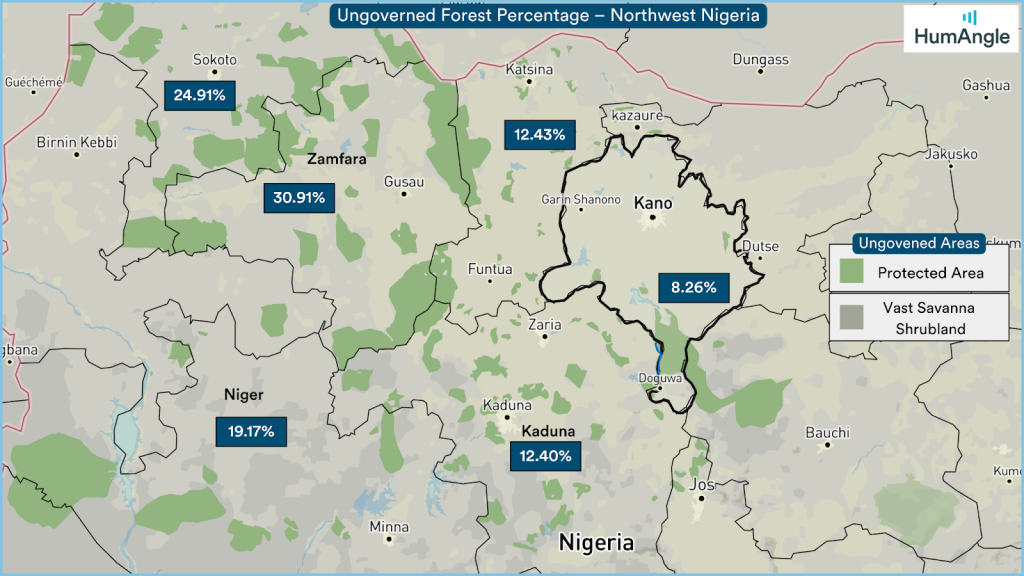

The crisis prevails across states like Kaduna, Zamfara, Sokoto, and Katsina, where non-state militia groups control areas near large forest reserves. Kano State, however, stands out as an anomaly. Despite its proximity to these hubs of terrorism, it experiences fewer incidents.

People in Kano have long believed that security threats, such as kidnapping for ransom, cannot thrive there. Many attempted abductions have been foiled, and while geography may be a physical reason, the absence of widespread insecurity is often attributed to spiritual protection.

However, that belief does not always hold true in rural areas.

Several other factors contribute to Kano’s distinct security experience. Unlike other states in the region, Kano does not face the same intensity of ancestral rivalry between farmers and herders. Even recent clashes between the groups in the state over land and resources have been linked to the increasing impact of climate change compared to most other drivers.

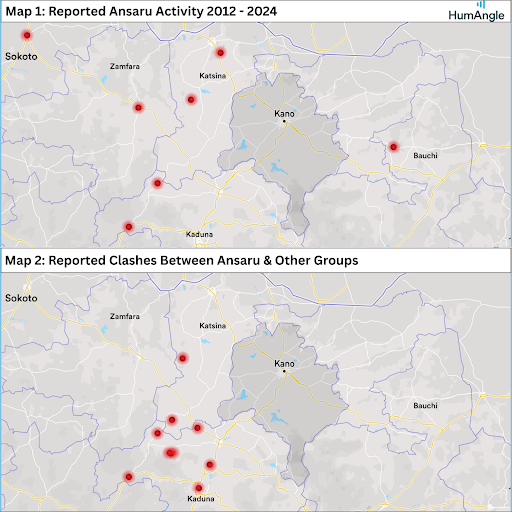

Historically, the state has also served as a transit command zone for attacks targeting other locations, a role dating back to the pre-colonial era of the Kano Emirate. In today’s context, the Ansaru terror network, which has maintained a presence in the state since 2012, rarely carries out operations locally. Instead, they use Kano as a base for coordinating attacks elsewhere. Again, unlike most states that serve as headquarters for local insurgent groups, this is a unique characteristic of Kano State.

Northern Nigeria’s ungoverned spaces are characterised by vast landscapes with sparse settlements and vegetation, providing ideal cover for terror groups. These areas, often near rural farming hamlets or temporary settlements, serve as connectors between forests, allowing terrorists to move between them and conduct operations with enough cover to travel en masse or rustle large numbers of livestock from local farmers, herders, and other rustlers.

Each state affected by terrorism has its own set of challenges. In Kaduna, the presence of rural communities far from government control and the high volume of travellers along the dreaded Kaduna-Abuja highway make it a prime target. Sokoto’s position near the local and international borders and its shared forests with Zamfara facilitate incursions by terrorist groups, while poverty and historical conflicts enhance the situation in Zamfara. Similarly, Katsina’s proximity to the forests it shares with Zamfara makes it vulnerable.

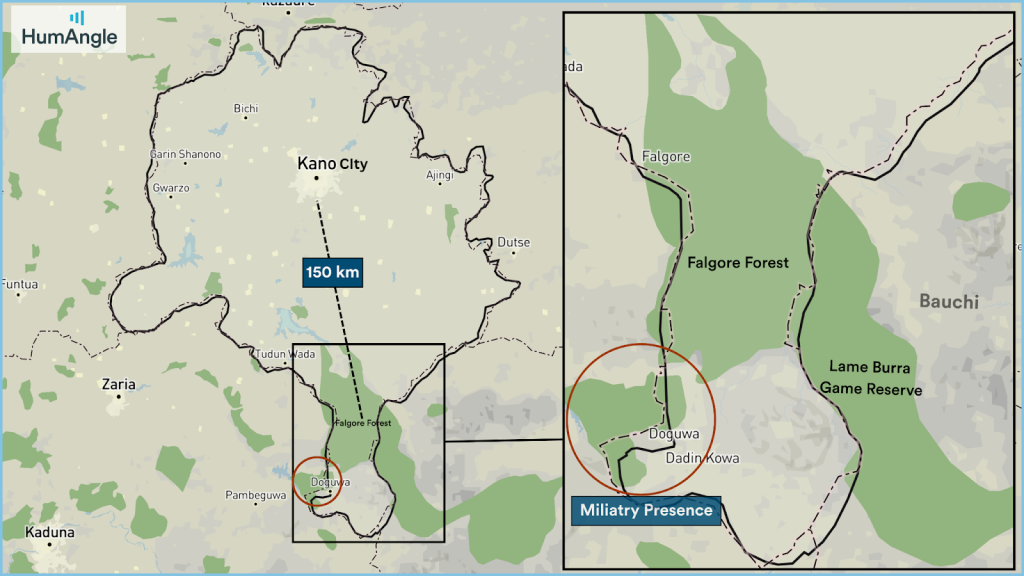

While Kano has not been immune to terrorism, it has managed to mitigate its impact to some extent compared to neighbouring states. This includes the state’s sensitivity to rising terrorism when early reports came in that armed groups were migrating to the state. The eventual militarisation of the nearby Falgore forest is one of the factors that may have contributed to debilitating the influence of local terror groups.

Despite this, reports indicate that the growing security threat in the region has also affected trade in Kano, the economic hub of the north, yet not nearly as much as its neighbour, and geography explains why.

That creeping threat has become a daily ache in Tsanyawa and Shanono. “The situation is getting out of hand,” Musa, a local, whose name we have changed at his request, said.

The border with Katsina is porous. From Tsanyawa, Yar Kanya, Gidan Mutum Daya, and Faruruwa, there is no thick forest to obscure movement, just flat land and a road that now carries more than goods.

“Along Tabanni, which links to Kano through Goron Dutse, they use the new bridge connecting to Katsina,” he added. “Before, a pond made it hard. But the bridge has become a blessing for them.”

The kidnappers come through that bridge, grab, and vanish back across the vast fields in Tsanyawa, which they use to go back to their hideouts in Katsina.

Ten local government areas in Katsina suffer daily attacks. Schools have closed. Entire villages were displaced. The vast, wild Rugu Forest offers these men shelter; from there, they cross easily into Kano.

The forest routes

Studies have revealed a network or pathway of insurgency running through Nigeria’s forests, utilised for rustling livestock, grazing cattle, and launching attacks on communities across the country. The affected states are vulnerable due to the geographic layout of nearby ungoverned spaces and their semi-government settlement peripheries.

From Sambisa to Gombe, Falgore to the savanna highlands of Plateau State, and through the infamous Kateri forest in Kaduna, the connectivity of forests like Kamuku and Kyumbana game reserves forms a crucial network. A state’s vulnerability, or relative resilience in the case of Kano, hinges on whether target communities fall within the pathways along these interstate forest networks.

The Falgore forest, approximately 1,000 km2 in size, is connected to Kano, Kaduna, and Bauchi and extends into Kano through three local government areas in the state (Tudun Wada, Doguwa, and Sumaila). Yet, according to estimates by the Geographic Information System (GIS), the forest covers less than 8.26 per cent of the state. This means that rural areas on the outskirts have fewer potential targets for groups traversing the forest, resulting in lower population densities worth terrorising along this axis.

The Falgore and Lame Burra Game Reserve in Gombe are connected and covers nearly 3,000 km², potentially influencing 5,000 km² (GIS Estimates) of adjoining lands and settlement areas in secondary locations. These areas consist of thinly forested shrubland pathways and flat agricultural farmlands cultivated by nearby locals. These sparse and remote settlements make them ideal transit points for terrorists moving between forests unnoticed.

Falgore forest lies 150 kilometres away from Kano city (the emirate). The natural shape with which the forest intrudes into the state serves more as a passageway through the southern extremes to neighbouring states with more accessible and profitable targets, such as routes used by herders massacring farming communities in Plateau State or the path towards the ungovernable spaces in Kaduna forest communities under the control of local warlords.

Efforts to address the security situation in Kano include setting up military checkpoints, which worked only as long as the groups were stationed, returning after each turn. In 2017, the state government provided land to construct a training facility in the Falgore Forest. To discourage terror groups from settling in the forest, the military conducted operations and hosted events in the forest facility.

“Nigerian Army (NA) troops in a bid to ensure the return of socio-economic activities which were hitherto hampered by activities of terrorists and other criminal elements, 1 Division NA in conjunction with personnel of Nigeria Police, Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps as well as local vigilantes and hunters embark on a special joint clearance operation in Falgore Forest and other flash points in Kano State. The clearance operation which is still ongoing is geared towards complementing the efforts of the standby troops at Forward Operating Base Falgore, with the ultimate aim of making sure that terrorists, kidnappers and other criminal elements from neighboring States do not infiltrate into the forest and any other part of Kano State to carry out their nefarious activities.”

— MOHAMMED YERIMA, former spokesperson of the NA in 2021.

The training facility is strategically located in the Dodowa Local Government Area of the state, one of the three LGAs intersected by the forest. Covering an area of 2,169 hectares, it sits just west of the Dogowa community, fortified amidst the natural concealment and protection of hills. While not situated in the forest’s heart, as reports suggest, its strategic positioning along the interstate boundary makes it a pivotal outpost. Positioned close to key pathways traversed by armed groups, the facility acts as a barrier, disrupting access to nearby forests. This vantage point allows for efficient monitoring of non-state actors entering or leaving the region.

Terror groups exploit these pathways to traverse into various states, perpetuating insecurity across the region. The position of the training facility and its associated zone of influence effectively cuts off access to nearby forests linking into Kaduna state, serving as a critical outpost to monitor the activities of non-state actors.

A series of interconnected forests form the transit network for terrorism in the northwest region. The Kyumabana forest, bordering the Kamuku reserve, is a significant hub for notorious terrorists in Zamfara State. Dogo Gide’s hideout is believed to be located here, with surrounding areas like Dan Sadau serving as his stronghold. This forest provides access to many communities in Kaduna and Zamfara,

The Birnin Gwari forests in Kaduna are also notorious hotspots for terrorists. Locals report terrorists using these forests as bases and transit zones for attacks on nearby communities, including acts of sexual violence targeted at women. Along this path are bordering areas such as Udawa, Buruki, Birnin Gwari, Sabon Gari, and Kotongora. These forests serve as hideouts for terrorists operating in Kaduna and extend into neighboring states like Niger, linking to other hotspots such as Alawa – Shiriroro axis, Pandogari, Kainji, and Munya wilderness.

To the north, these forests provide pathways into the Kywamban forest, where terrorists like Dogo Gide operate. They use these routes to abduct people along the Kaduna highway and retreat to their hideouts in Zamfara State. The hills and forests connecting to Kaduna are characterised by vast savannah lands with sparse vegetation, dotted with small communities suspected of harbouring terrorists. Areas like Kamuku, Rijana, Jere, Doka, and Kagarko are vulnerable, with interconnecting pathways leading to neighboring states like Niger and Plateau. South of this lies a network of Savannah forest pathways leading to the border areas of the Federal Capital City. Terrorists exploit these routes to infiltrate suburban areas near Bwari for kidnapping operations.

From here, the path leads through Falgore and Lame Burra forest reserve, which further connects to Yankari Game Reserve, Bauchi, and proceeds through Gombe Forest and Sambisa Forest in the Borno State. Before now, terrorists would traverse through these forests without hurting locals thriving in nearby Kano communities. The situation has since changed, with criminals terrorising unprotected locals in the state.

For instance, when Rabiu Faruruwa went to a local market in his village, he returned home a dead man. Rather than sending one of his 16 children, Rabiu decided to go to the market himself. No one knew that fate had chosen that moment, his second trip to the market, as the end of a long, quiet life.

Suddenly, in the market, the gunfire started. There were no warning signs. Panic erupted. People screamed. Stalls were overturned as vendors and shoppers fled in every direction. But Rabiu couldn’t run. His knees had long stopped cooperating the way they once did. In the chaos, he stumbled and fell.

“He was shot dead,” said his 27-year-old son, Abdullahi, his voice thick with grief. “He had just wanted to help the family. He always did.”

Since that day, Rabiu’s household has changed.

“Faruruwa hasn’t felt the same,” said Abdullahi. “People now think twice before going out, especially the elderly. We’re all shaken.” But they have no plan for relocating. Instead, they are calling for a more secure presence.

“The government needs to do more. Our border with Katsina has exposed us, and we have nowhere to go. This is our home,” he said.

With the trans-forest flow through Falgore now disrupted, only one central corridor remains: the borderlands between Katsina and Kano. This route has featured in several recent incidents in Kano. Typically excluded from known trans-forest pathways, this area lacks the dense forest cover of the south (like Falgore) and instead consists of vast, largely ungoverned stretches of dry shrub and grassland forest separating the two states. There are a few forested patches; one roughly half the size of Kano city, and others about a quarter each. While smaller, these pockets are sufficient to host armed elements in transition between the two states, positioning this area as a new frontier for emerging attacks that could deepen insecurity in Kano.

How did the northwestern region fall into the hands of criminal networks, with Kano as a key transport hub and the latest victim of armed violence?

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), an independent global non-profit collecting data on violent conflicts and protests, provides a timeline of the crisis’s evolution in the northwest. Initially plagued by cattle rustling, the region witnessed a transition to kidnapping as cattle stocks dwindled. With kidnapping targets becoming scarce as people moved out of the states, armed groups shifted tactics, imposing tax levies on local farmers.

Here is the timeline of the evolution:

- 2011 – 2019: Cattle Rustling

- 2019 – 2022: Kidnapping (Cattle Stock Depleted)

- 2019 – 2024: Levies on Farming Communities (Decline Since 2023)

This timeline illustrates the events across the states, showcasing the adaptive nature of armed groups in response to changing circumstances.

According to ACLED data, the leading non-state actor group responsible for most violence against civilians in Kano State is Unidentified Armed Groups. These groups account for 71 per cent of all incidents (74 cases) recorded between 2010 and May 2025. The label is an umbrella term used for various actors, including armed political thugs and terrorists who are neither affiliated with Boko Haram nor identified as armed herder groups. As seen across much of the North West, their presence in Kano spans the entire 15-year period, with a noticeable uptick from 2018 onwards. They were also responsible for several cases of election-related violence in 2015, 2019, and 2022.

Boko Haram (JAS) follows next, with 16 recorded incidents between 2011 and 2013, before the group’s insurgency reached its peak nationwide. Their presence in Kano was short-lived and faded mainly before their most violent years.

Only one ISWAP-related incident was reported between 2010 and 2025. While it’s possible that some of their operations were misattributed to unidentified groups, ISWAP typically claims responsibility for its actions. This suggests that their activities remain uncommon in Kano, unlike in northeastern states, where they are more active.

Abdullahi Usman does not want to leave Tsanyawa in Kano state. His father’s grave is here, and his house stands on soil tilled by generations.

“They came at night. We ran. Later, we heard they took our neighbour,” he said, disturbed over the insecurity in his beloved community. His neighbour, Alhaji Akano, was also abducted and returned after some time. People gathered to welcome him, and someone even uploaded his picture to social media in celebration. There were prayers, smiles, and gratitude. But everyone knew it was temporary because the insecurity had become frequent.

Some perceived wealthy people have already started moving out of Tsanyawa to neighbouring towns with a sense of safety. Still, Abdullahi said he would remain in Tsanyawa because he had nowhere to go.

“As of now, nobody is talking about self-protection, but if it requires that we have to protect ourselves, then we will have no other options,” he said.

In Faruruwa, military men sit idly at the post, waiting for instructions, vehicles, and orders that rarely come.

“They’re here,” a resident said. “But when attacks happen, they come late. Sometimes, not at all.”

There is a police station in Tsanyawa too. But it is thin on men and thinner on weapons. When gunshots echo in the night, people no longer dial emergency lines. They just lie low and wait.

Aisha Musa used to walk to the next village to see her sister. Now she stays home. “Unless someone goes with me, I won’t go,” she said. “We all feel exposed.”

In those villages that were once attacked or feared being attacked, markets close early, children are kept indoors, and even weddings are sometimes held quietly in other towns.

A year ago, the Kano State government created a special task force to protect schools after many cases of school abductions were reported in northern Nigeria. So far, no school abductions have occurred in Kano.

“If it happens, we won’t know who to call,” said Ibrahim, who narrowly escaped the Faruruwa attack.

Ibrahim was originally from Kano city, but his work as an enumerator made him a constant visitor to Shanono. He found a place in Faruruwa. When the recent attack happened, he was there, and he thought the attackers were targeting him and his colleagues.

“We had to leave early in the morning because we thought we were the targets,” he told HumAngle.

Musbahu Shanono's nostalgic journey to his village in Kano State, Nigeria, has turned into a perilous endeavor due to increasing kidnappings by armed groups crossing from Katsina.

Once a peaceful rural community, Shanono and its neighboring villages Tsanyawa now grapple with distrust and fear as informants aid kidnappers and criminals exploit porous borders. Despite military presence and checkpoints to disrupt these crimes, attacks persist, leading to abductions, killings, and eroding trust among locals, causing many to consider self-defense or reluctantly accepting the instability.

Security in the region is undermined by vast ungoverned forest areas, forming transit hubs for terror groups taking advantage of northern Nigeria’s complex landscape. Although Kano has historically been shielded from widespread terrorism due to strategic military initiatives and geography, recent incidents hint at a deteriorating safety net.

The lack of communication and response from local authorities during attacks amplifies residents' sense of vulnerability and inability to rely on traditional security mechanisms.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter