‘I Just Drink Water And Endure’: Ramadan In A Nigerian Displacement Camp

More than 600,000 people have been forced to flee their homes as terrorists continue to prowl the country’s North West. Many of these families observe the fast in a state of uncertainty. Others who get enough nurse a familiar fear: what happens after Ramadan?

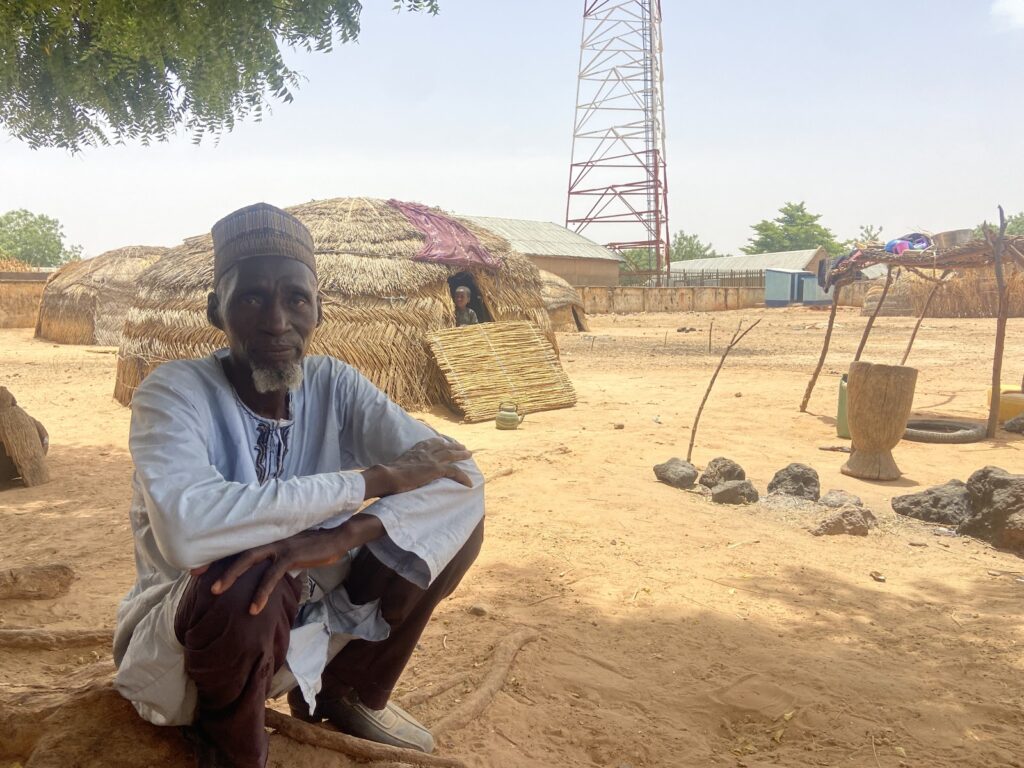

It was a little after 12 p.m. on a Thursday in late March. The scorching sun scalded through the thatched roofs of the makeshift huts occupied by internally displaced persons (IDPs) at the Rabah displacement camp in Sokoto state as men gathered under the shade of a dogoyaro tree along one of the camp’s fallen fence, looking to escape the sweltering heat.

Umaru Bagobiri slouched and propped his chin in the palm of his left hand. He seemed lost in his thoughts. Or perhaps hungry.

It is the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Usually, across the world, Muslims welcome the season with excitement and dedicate themselves to a month-long prayer and worship. During the month, they wake up before sunrise to have a meal known as sahur and then break their fast with the iftar at sunset. Several weeks or days before the month, Muslims would usually go shopping and stock their houses with food items and other necessities.

But many of the 886 Muslims at the camp and hundreds of thousands across the region continue to struggle to put food on the table for the rites. For three nights or so, Umaru had not had anything to eat or drink since dawn. And when it was sunset, at the end of the day’s fast, he was not so sure there would be food for his family.

“Life has been very difficult and devastating compared to where we came from. I used to welcome Ramadan with open arms and stocked the house with food. But since we got here, eating has been a nightmare. And it’s not any different this month,” Umaru told HumAngle.

The 65-year-old raised his head and looked wistfully into the far distance. Earlier that day, immediately after the pre-dawn meal, he had taken only water and given up the bowl of kunu (millet drink) in the house so his wife, Nana, and sons could take one gulp or two each for the fasting. But he was determined to get a proper meal before sunset. So, he grabbed his axe, perched it over his shoulder, and headed into the forest for firewood.

Before he left, his wife muttered a soft prayer, as usual, for their situation to change and enjoined him to endure this life that was forced on them. She’d always been like that, even before they were displaced from their home in Taguwa, a village in the Rabah area.

No aid, barely any livelihood

Umaru fled Taguwa after terrorists, locally known as bandits, attacked his home and many others one night around 9 p.m. He was already in his bed when the shots of terror rented the air. That attack single-handedly ended the lives of many of his friends and distant relatives. He wound up with many others, including his wife and sons, at the displacement camp.

Northwestern Nigeria has been a hotbed of criminal activity for close to a decade now. Terrorists have continued to raid and loot villages and conduct mass killings that have resulted in the deaths of no fewer than 12,000 people (as of 2021) and displaced hundreds of thousands more. They also run a million-dollar kidnap-for-ransom enterprise, abducting locals, including schoolchildren, to sustain their operations.

It used to take Umaru four hours to return whenever he entered the bush for woods. On busy days, he said he made an average of ₦850. And on some days, he made nothing. He hoped this day wouldn’t be one of them.

“If I come back, I can sell the firewood for 700 to 1000 naira, which wouldn’t even buy Garri or be enough for me and my family. During iftar, we take pap. And if it remains, we keep it for sahur. But most of the time, I just drink water and continue with my fasting because there is no food to eat,” he added.

Many camp residents said they had not received food rations for as long as they can remember. Instead, they depend on kind donations from people around. A survey conducted by REACH, a humanitarian initiative that provides data on crisis and displacement, found that only 10 per cent of those in need have received any form of assistance in the region, leaving thousands without food or the necessary support.

It assessed 11,090 households in 1,335 settlements across 71 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in the three frontline states of Zamfara, Sokoto, and Katsina. According to the survey, 98 per cent of displaced and non-displaced families were facing severe forms of humanitarian crises due largely to the tripartite issues of conflict, climate change, and poverty.

Aliyu Halilu clasped his hands tightly behind him as he walked towards his hut. The fireplace beside the shelter appeared abandoned. Since Ramadan started in early March, he says, his family has not lit a single matchstick to prepare any meals. And just like many others in the camp, he has also been living on the goodwill of wealthy individuals who feed the vulnerable during the holy month.

Aliyu left the village of Tabani after he was abducted by terrorists who had invaded his home in the thick of the night one Saturday in 2022. The 70-year-old had to sell his possessions to raise a ransom of ₦1 million and a motorcycle before he was released thirty days later. Before then, the terrorists had earlier attacked the village and made away with their cattle.

Those pockets of incidents were the last straws for him. “They took everything I had ever worked for. They took my sweats,” he said metaphorically before pointing out that he was observing his second Ramadan in the camp and was still struggling to get used to it.

“Before all of this trouble started, I used to look forward to Ramadan. It comes with its own ease and calmness. I made sure my families were comfortable and didn’t have to worry about what to eat throughout the month,” he recalled. “But here, fasting is different. Sometimes, I fast without eating anything for sahur and don’t even know what is to come for iftar. I will just drink water and fall on the bed.”

‘I miss family gatherings’

Apart from the prayers, worship, and abstinence that define the holy month, it’s also a time families work out their differences and bond with one another. Ardo Bako, 52, missed just that. He said it was one of his most cherished moments during Ramadan.

Every evening before iftar, his eldest daughter would spread mats under the tree in their compound. He would as well have bought kankara (ice block) and cow milk. His brothers would do the same while his wife prepared rice and sometimes pap for the family to feast.

He remembered Nana Hawau, his mother, who wouldn’t join them until her ‘annoying’ cats were properly fed. Bako still remembers almost everything, even though they are all now remains of his scarred memories of home.

“Fasting here has not been easy,” he started briefly. “Sometimes we eat, sometimes we don’t. We’re just enduring. But before all of this crisis, especially during Ramadan, I was always excited. Food was never our problem because I had a farm. Before the time for iftar, we would have gathered under the tree, waiting for my wife to serve us rice and sometimes pap.”

His brother would come with cow milk for everyone.

Everything was going really well for Ardo and his family until the day terrorists besieged their village, Tabanni. He left with his family for the camp in the town, leaving his source of livelihood behind. “Since we got here, things have not been the way they were. In fact, we don’t have anything here, but we thank God for the peace,” he said.

But what happens after Ramadan?

A blue minivan pulled up at the entrance of the Ramin Kura displacement camp in the heart of Sokoto. Two young men alighted as children swarmed towards them. They had come to deliver a bag of rice and some cash for the camp’s residents. Later in the evening, minutes to dusk, there would also be jollof rice in disposable packs and grains donated by individuals and non-governmental organisations in the state.

They also have access to food aid and cash transfers from the state government.

But Aisha Murtala nursed a familiar fear. Many residents of the camp struggle to eat and access healthcare. Other basic needs for proper hygiene have become extremely difficult for many to come by, a situation that prompted frontline medical humanitarian group Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to describe the humanitarian situation in the North West as ‘catastrophic.’

The region has also seen an alarming increase in the rates of malnutrition. It is estimated that around 2.6 million children have severe acute malnutrition in the country, out of whom a whopping 20 per cent are in Sokoto, Katsina and Zamfara states.

“We get all of this food now, alhamdulillah. But the problems we’re facing have not vanished because of that. We need proper shelter, medical care and schools for our children. None of the children in this camp have any form of formal education. Yes, we are getting food now, but what happens once Ramadan is over?” Aisha asked.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter