Farmers Tried To Protect Their Land From Floods, It Divided Communities

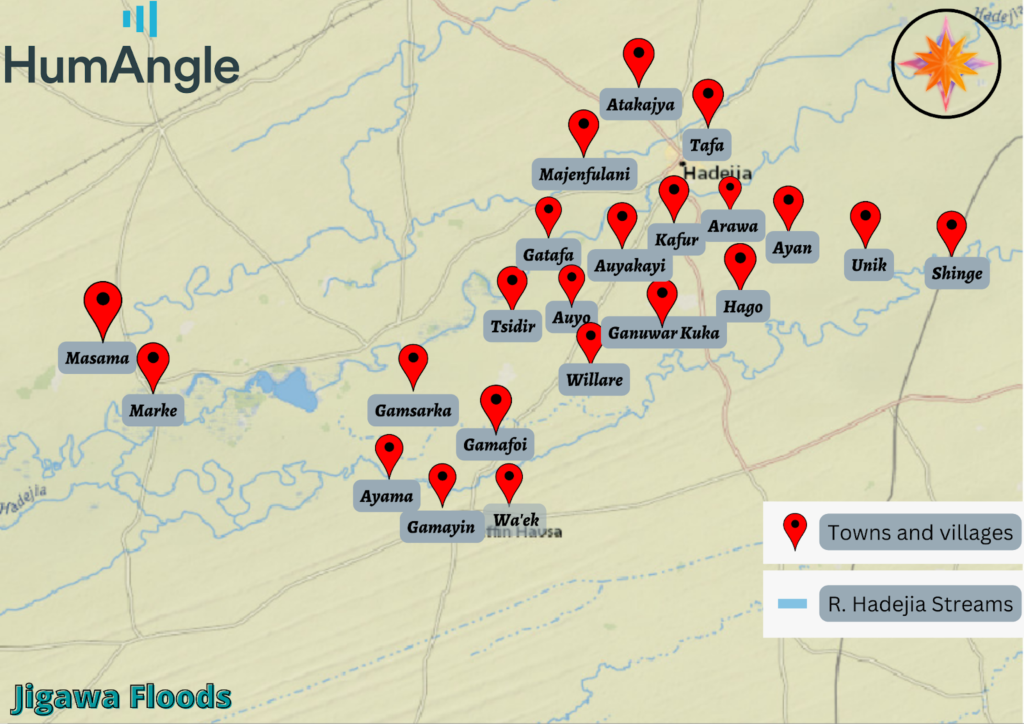

When the water overflowing from Haggo met the flood from Hadejia, communities began working on embankments to prevent the destruction of their homes. However, this created tension among them.

Even before the scientists were predicting torrential rains would cause devastating floods in many Nigerian states, Hadejia people knew that the high frequency of floods in their villages and towns every August meant they were in for trouble. After all, it has happened that way for years.

Mahmuda Ibrahim, 30, of Kubayo village in Hadejia, said it had been like this since he was born. “We grow up seeing our parents struggle with this disaster,” he lamented, “but successive governments have refused to do anything about it. It has destroyed our homes, farmlands, and foods.”

So, when heavy rain began to fall in early Aug. 2022 and rivers swelled up, some locals began working on a desperate project: to build an earthen embankment to protect their farmlands.

Men from the village grabbed their spades and got to work, flinging shovelful after shovelful of earth up to form a dyke.

“We began working on embankments in the farms for two weeks, day and night, but the water was too much for us, so we left the farm and moved to homes, but we couldn’t stop there either. We had to leave our homes with only what we could carry,” said Mallam Abubakar Tandamu, explaining how he lost most of his belongings to the disaster.

That was how people started fleeing from their low-lying communities to uplands where they thought was safer.

But the places that had been safe before would not be safe this time.

“We took some of the important things in our houses and fled to dry areas,” Mallam Hadi told HumAngle in a school named Bello Bayi, converted into an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp in Hadejia.

The school itself was, at the time of this interview, submerged in water. Flies buzz around in the morning, and mosquitos are rampant at night, increasing the likelihood of an outbreak of disease.

Doctors were there to control the situation, giving the sick medicine and advising the healthy on how to survive the disaster.

Hadi and other victims had previously moved to two villages along the Ringim-Hadejia road in search of dry land, but the flowing water had consumed everything.

The school they were in was relatively safer, yet they still considered leaving for drier ground.

Hadi has not yet decided where to move to because most of the areas around them have also been affected. HumAngle counted 42 residents, some fighting for survival by working on embankments.

According to local official statistics, 134 people have died, 76,887 people lost their homes, and over a trillion naira in property has been lost as a result of the disaster.

In one of the IDP camps visited by HumAngle in Gandun Sarki, over 900 victims, mostly women and children, were using public school classes for shelter. Others, especially men, were forced to the roadsides and petrol filling stations for shelter.

Divided communities

The disaster has divided communities, creating a struggle for space among the people. This makes some displaced unwelcome in host settlements.

During the first three days of continuous rainfall in August, some communities blocked waterways (especially those from Hago), fearing that the flood would consume them all. Now that was only one part of the problem.

In the month of August, the Hadejia-Jamaare River Basin Development Authority announced that the water would be released, so residents were asked to clear waterways. When the water was released in the month of September, it overflowed through some communities and that caused misunderstanding between them and the villages that refused to open their embankments.

The unaffected areas were concerned that the overflowing water would wash away their belongings. They feared that the embankment they put would be removed by the affected communities and so saw the need to protect their boundaries.

HumAngle met some of them in Auyo’s Ganuwar Kuka village. Frustrated with how the water was finding its way, they were armed with sticks and braced themselves for clashes with neighbouring communities trying to remove their embankments.

The day our reporter arrived at Ganuwar Kuka, the tension rose because some of the enraged youth saw the reporter as someone who was there to expose the situation. He was beaten until he was saved by the village chief.

“Their fear was that after they were abandoned by the authorities, journalists covering the issue would expose how they were not allowing the water to pass through their villages after they erected blockages,” Bashir Sharfadi, a journalist with Freedom Radio who was also covering the situation, explained.

Unsure of where to go, displaced people sought refuge in schools that were also affected. An aged woman with children who didn’t want her name mentioned said she has lived in fear since the day she found herself there. Her worry was that if schools resume, she would have nowhere else to go.

“For the time being, this is our safe haven. We have nowhere to go because the water has destroyed our homes,” she explained.

“My husband can’t build a house from scratch in a month or two. His farm has gone, my goats too. I don’t think about it now because I’m afraid of what the future holds for us.”

Annual cycle of disaster

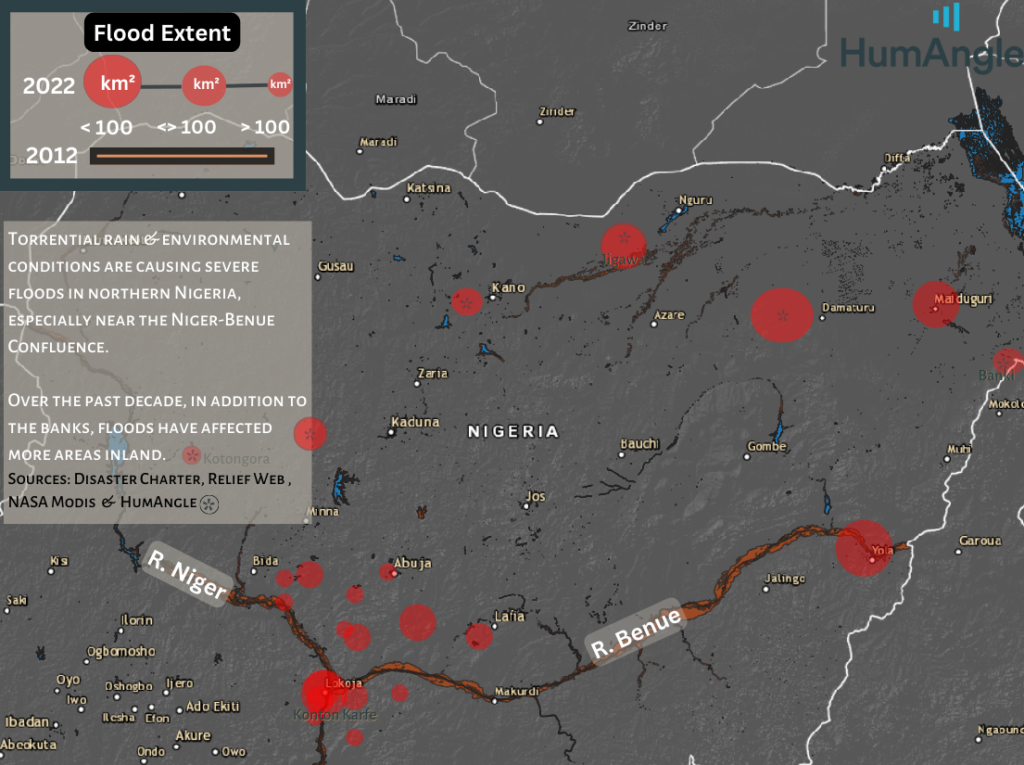

This is not the first time Hadejia is experiencing a disaster of this magnitude, but it is the worst in recent years. According to reports, Nigeria has not seen this level of destruction in a decade, with several areas around the country affected. NIMET predicted and warned that flooding could last until the end of the year. But for Hadejia, every year brings new challenges.

In September 2020, the town experienced torrential rains, which flooded many of its villages, sweeping farmlands and settlements and displacing thousands of people. The tragedy made headlines and drew the attention of social media influencers who raised funds to help victims, the majority of whom were women and children who couldn’t find bread to eat. Food and medicine were donated to them, but residents said that was only a temporary response.

“Every year, we see this kind of emergency assistance, but the root cause of the problem is never addressed,” said Aliyu Kabiru.

Residents insist the River Hadejia is the main cause of the disaster, but they attribute some factors to Jigawa State’s geographical landscape which is said to be relatively low-lying compared to neighbouring states, especially those close to the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands. The vast River Hadejia overflowed to various locations in its area two years ago in 2020, killing at least 40 people and displacing thousands. During the 2018 rainy season, approximately 30 people were killed as a result of a flood that ravaged over 68,000 hectares of land in local government areas near the river.

The river divides into three channels in the Hadejia Nguru Wetland, where devastating floods was also recorded in Yobe State, the Marma channel, which connects to the Jama’are River from Bauchi. There, bridges frequently collapse around the small Burum Gana River which is known for seasonal overflow.

Many communities in the northern part of the river are constantly at risk of flooding, which destroys socio-economic activities in the vulnerable communities. Some of the dams connected to the River Hadejia, like Tiga in Kano have also flooded due to River Hadejia’s oversaturation that flows down to them and destroys farmlands.

For decades, there have been numerous calls to control the river’s overflow, but no project to address the issue has been launched since the first republic. In 2014, Hadejia Local Government authorities planned an embankment project on the River Hadejia but what was put was sand bags which was not effective in stopping the flood. During dry seasons, farmers were also accused of destroying the embankment for irrigation purposes.

According to a local journalist, Abubakar Tahir, the release of water from the Hadejia river was a major factor in the disaster. Authorities, however, stated that the water must be released in order for it to pass through the dams connected to it as required by law. According to them, the issue is not the water from Hadejia river, but rather the saturation of the lands with water during the rainy season.

Looming food insecurity

Agriculture provides a source of livelihood for nearly 90% of Jigawa’s population, the majority of whom live in villages and towns like Hadejia. Jigawa, like other northwestern states, is a rice producer. One of its farming headquarters is in Hadejia. Agriculture accounts for 60% of the state’s GDP, making it an agrarian economy.

However, this year’s floods have washed away farmers’ dreams of reaping the benefits of their labour, making food insecurity a matter of when rather than if.

“The state government estimated that about a trillion naira worth of properties were lost, but I don’t think they included mine,” said a farmer, Abdulaziz Gariyo, who lost everything in his vast farm called Idi Custom Farms. “I was expecting 1500 or more sacks of produce, but everything has gone now.” He added that his farm employs over 200 people who will receive no compensation as a result of the disaster.

He is not the only one who lost as much. Mallam Abubakar Tandamu, said he had no idea how much he had lost. “But I don’t have anything right now,” he admitted. The person who used to have enough food to feed his family for a year is now waiting to be served garri and bread as part of the local government’s humanitarian assistance to IDPs.

He was sleeping with his children at a petrol filling station, which he described as “very uncomfortable”. And as the water began to recede, he planned to return to rebuild his home.

Mallam Usman’s animals were also taken away by the flood. “When the water took them, I was helpless. There was nothing that could be done to save them,” he recalled. He was raising goats, which he said were not water-tolerant. “They didn’t die in front of my eyes, but I had to abandon them to save my life and my family.”

The greatest concern right now is the potential for food insecurity as a result of the disaster. Northern Nigeria is the country’s food bank. The region is suffering from a number of factors that could lead to food insecurity, including violent clashes and flooding in almost every part of the sub-region, including some parts of Jigawa that have started experiencing farmer-herder clashes.

Flooding has already begun to have an impact on Northern Nigeria, as the Lokoja River in Kogi State overflowed, clogging roads and threatening motorists and vehicles transporting petroleum and gas to the region from the southern part of the country. This has caused a temporary fuel scarcity that affects businesses.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that flooding in Nigeria will cause food insecurity and inflation of food prices in the country. According to Mai Farid of the African Department of the IMF, “the floods have affected some of the transportation networks which makes it even harder for food to be transferred into the country or even [export it] out in any essence storage.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter