How Facebook’s Monetisation Programme is Fueling the Misinformation Economy in Northern Nigeria

The more scandalous the claim, the greater the traffic. And with traffic comes income.

The ring light in Amina Yusuf’s* room stood near an old white wardrobe. For months, it remained unused, except during the occasional recordings where she mimed along to Hausa love songs, glancing between her phone screen and the mirror at the other side of the room. These moments were fleeting, unsure steps in her experiment with social media, particularly TikTok.

But when the news came that Facebook had rolled out monetisation features for content creators in Nigeria, something stirred. Opportunity, like the sudden spark of light, loomed and offered a new possibility. Not fame, no – at least not yet – but fortune, or its illusion.

“As soon as I heard about it,” she said, fiddling with the edge of her veil, “I knew this was a way to earn from what I was already doing.”

She speaks with the assurance of someone who has discovered a private economy within a public world. Amina converted her dormant Facebook profile, once used to scroll aimlessly through posts and video reels, into a professional page. She followed every breadcrumb Facebook’s interface dropped: optimize your bio, post consistently, engage followers, and cross-promote from Instagram. Soon enough, the app crowned her eligible for monetisation.

And that’s when her trouble began.

In this algorithmic marketplace, virality is currency. With 190 thousand followers on Facebook, her reach was growing – thousands of views, shares, and comments flooding her posts. Amina’s strategy was simple: find trending TikTok videos and repost them. It didn’t matter whether the videos were true or false, informative or inflammatory.

“My job is just to share,” she said. “It’s the viewer’s responsibility to figure out if it’s true or not.”

“Sometimes I earn between 10 to 15 dollars a day,” she said, not with pride, but a sense of surprise. “That’s a lot of money for someone like me. I even paid my school fees with it.”

As a university student in Northern Nigeria, where classrooms are overcrowded, lectures often suspended, and lecturers underpaid, she says her digital hustle has made her richer than her lecturers.

“I earn more than them,” she said plainly. “Imagine that.” She referenced how recently a university professor revealed the dire professional conditions they find themselves in.

To digital rights activists and fact-checkers, Amina is not just a clever student seizing a modern opportunity. She is part of a growing ecosystem that profits from confusion. What she calls content, they call misinformation. Monetised misinformation.

Facebook’s monetisation in Africa, especially in Nigeria and particularly in the northern part of the country, has become a double-edged sword. On one hand, it democratizes income in a region that ranks high in poverty rate. On the other hand, it rewards spectacle, sometimes at the expense of truth. Sensational headlines, recycled conspiracy theories, emotional hoaxes: these are the new exports of a digital continent eager to be seen, eager to be paid.

Amina does not deny this. But she also does not apologise.

“I don’t make the videos,” she said. “I just share what people have already posted. If it makes people comment and watch, that’s all I need.”

Her profile on Facebook is a mixture of different videos – politics, religion, celebrity gossip, football, and everything that may generate engagements. Among this, is the amplification of information disorder originally shared by the creators of the videos.

For example, in a Facebook post that garnered over 60 shares, she amplified a false claim that Osun State Governor Adeleke had announced Babagana Zulum would spearhead the defection of five Northern governors to the new coalition of ADC. Despite the claim being publicly debunked, the post is still on her profile.

An algorithm designed for outrage

By design, Facebook’s algorithm privileges intensity over integrity. According to the platform’s own documentation, content that provokes strong emotional reactions – anger, fear, shock– is more likely to spread. For many users in Northern Nigeria, where Facebook doubles as both a social space and a news source, this has created a chaotic digital environment where engagement is currency and accuracy is often overlooked.

“Facebook isn’t just a platform here,” said Bashir Sharfadi, a journalist based in Kano. “It’s the main source of news for millions. So when influencers post fake news, the impact is immediate and vast.”

A 2020 report by the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) West Africa, revealed that most of the viral posts flagged by Nigerian fact-checkers in the previous year originated from influencers who directly benefited from Facebook’s financial incentives. The rewards are tangible and tempting.

One such influencer, who regularly posts unverified videos to nearly a million followers, put it plainly: “It’s about engagement, not content.” He explained how influencers operate in coordinated communities, often through WhatsApp groups, sharing what trends, what triggers reaction. “The only reason we avoid some kinds of content, like nudity, is religious. But many others still post that too.”

The more scandalous the claim, the greater the traffic. And with traffic comes income.

But Sharfadi warns that the crisis goes beyond the individual pursuit of profit. It has become institutional: a digital ecosystem where misinformation is normalised, defended, and scaled.

“Our biggest challenge isn’t detecting lies,” he said. “It’s competing with the incentives that come with spreading them.”

But Sharfadi has more concerns. People believe misinformation and they don’t care even after it is fact-checked.

In one recent case, a TikTok video targeting an activist named Dan Bello was re-edited and republished across Facebook and WhatsApp. Dan Bello is a popular Hausa vlogger with millions of followers on Facebook, TikTok, and X, posting mainly on accountability in governance.

The manipulated clip, falsely portrayed Dan Bello as ‘an enemy of Islam’ supporting an attack on Muslim clerics by showing him raising thumbs up on an audio attached to the video. It gained massive traction. The result: a popular cleric condemned Dan Bello publicly, sparking backlash that lingered even after the video was proven to be doctored.

“Even when the cleric apologised, people still believed he had been threatened into doing so,” said Sharfadi. “The damage had already been done.”

Another case involved one Sultan, a TikTok influencer known for posting commentary on current events. During the recent Israeli-Iran conflict, he claimed that Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu was hiding in a bunker, near death. The clip was later manipulated to feature an image of Nigeria’s President Tinubu and circulated widely.

Sultan is now in jail.

“He was arrested in Kano for something he never did,” posted his lawyer on Facebook. “There was no investigation. No effort to verify. Just a swift response to digital noise.”

The story of Sultan is a portrait of a system where the line between user-generated content and criminal liability is dangerously blurred.

Who bears the burden?

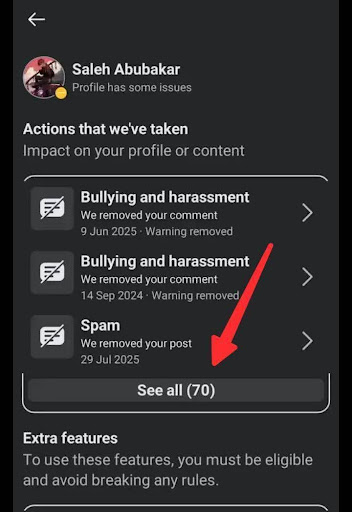

In response to the growing crisis, Meta—Facebook’s parent company—has recently taken down and demonetised dozens of accounts for violating its content policies. But enforcement remains scattershot.

One influencer interviewed for this report admitted to receiving multiple warnings. Yet his account remains active and profitable.

About what caused a restriction on his account, he admitted, “I know it’s wrong, but if I stop, someone else will do it. So what’s the point?”

Critics argue that Facebook’s moderation policies are inconsistent and reactive. Content flagged in English may be removed, while misinformation in Hausa, spoken by tens of millions, is often overlooked.

“What we see is a system where the platform benefits, the influencers benefit, and the public suffers,” Sharfadi said. “It’s not just about demonetization. It’s about influence. These pages, with their massive followings, can be rented. You pay, they publish whatever narrative you want.”

The commodification of disinformation has taken root. Several influencers are now operating as pay-for-post vendors, spreading political propaganda and conspiracy theories on demand.

Fact-checkers like Muhammad Dahiru believe that Facebook must go beyond machine learning and invest in people—moderators fluent in local languages and cultures, equipped to flag false content in real time.

“We need language-specific moderation, especially in Hausa, which is the lingua franca in Northern Nigeria,” Muhammad said. “Otherwise, misinformation will remain the most profitable game in town.”

He added, “There must be accountability. Either platforms police themselves, or governments will do it for them. And when governments control speech, history reminds us what follows.” Muhammad believes the work against misinformation is shared responsibility “between the government, Facebook, and civil society organisations.”

For now, Northern Nigeria’s digital public is left to sort through a feed where facts and falsehoods blend seamlessly, where a student like Amina can pay tuition with profits from misinformation, and an activist like Dan Bello can be condemned for something that never happened.

The asterisked name is a pseudonym we have used at the source’s request to protect her against backlash.

Amina Yusuf, a university student in Northern Nigeria, transformed her Facebook profile into an income-generating page by reposting viral content, including misinformation, after Facebook started monetizing content in the region.

This has afforded her earnings that surpass those of her lecturers, contributing to her education fees. However, her actions are part of a broader issue where Facebook's algorithms prioritize sensational content, often leading to the spread of misinformation for profit. This has sparked concerns among digital rights activists about the ethical implications and the normalization of misinformation on social media platforms.

In Northern Nigeria, where Facebook is both a social and news platform, misinformation spreads easily, often with considerable economic incentives for influencers. Despite attempts by Meta (Facebook's parent company) to curb violations, inconsistencies and sporadic enforcement allow misinformation to thrive, particularly in languages like Hausa.

Critics argue for more localized and culturally aware content moderation, as misinformation poses significant risks to societal truth and public discourse, signifying a shared responsibility among tech companies, governments, and civil society.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter