How COVID-19 Upset Family Planning Services, Threatened Women’s Lives

The deadly combination of a rigid lockdown, health workers’ industrial actions, and economic hardship occasioned by the pandemic led to a wave of unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions across Nigeria

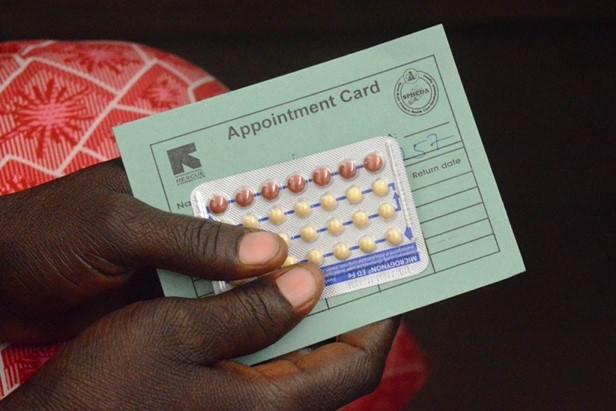

Omolara* had an unsafe abortion this year and it nearly killed her. Since she gave birth to her first child last year, she has been faithfully receiving contraceptive injections every three months. After a lengthy conversation with her husband, they had agreed child spacing was in the family’s best interests and that the injection was their preferred method.

But they were not expecting the outbreak of a new coronavirus, let alone that it would affect billions of lives, including theirs, in unimaginable ways.

Nigeria’s first case of COVID-19, an infectious disease that broke out in December 2019, was announced on February 27. A month later, the federal government imposed restrictions on movement in Abuja, Lagos and Ogun states, and this was soon adopted by other state governments.

The government of Ondo State, where Omolara lives, imposed a 12-hour curfew from April 14, with the only exceptions being the sale and purchase of food as well as emergency medical needs.

The streets became deserted. Businesses were shut down. And Omolara, who before was apprenticed at a tailoring shop, was stuck at home with her husband. As she could not visit the State Specialist Hospital in Akure for her dose of contraceptives, which was due for renewal by mid-March, she soon became pregnant.

It was way too soon, she thought, especially not in her financial circumstances, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. And especially not only about a year since her last childbirth. Scared, she started seeking ways “to flush it out”. She visited a neighbourhood chemist and explained her predicament. They recommended some drugs, which she said ultimately worked.

But along the line, the bleeding became overwhelming. It was so excessive she had to exhaust one pack of Virony sanitary pads within three days. She had no idea what to do, so she returned to the drugstore and bought a set of painkillers. Omolara passed outㅡand she is still not sure for how long.

“By the time I opened my eyes, I had been admitted at a private hospital,” the 30-year-old nursing mother recalls.

She was released after two days of regaining consciousness but not before coughing out N100,000. Having lost their sources of livelihood to the pandemic, Omolara and her husband had to borrow from families and friends to raise the hospital bill, and they are still not done paying back the loans. She is even more agitated because she would have paid about a quarter of that amount were it a state-owned health facility.

Health experts have observed an increase in unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions during the lockdown. Dr Omolaso Omosehin, head of the Lagos Liaison Office, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in July, blamed this on the delay in the distribution of family planning commodities during the period.

Recognising how the pandemic could spell danger for maternal health, the World Health Organization (WHO) cautions that access to contraceptive services remains essential during the outbreak.

“Contraception and family planning information and services are life-saving and important at all times,” the organisation says on its website. It explained that by preventing the negative consequences of unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortion, and sexually transmitted infections, contraception could help reduce the pressure on already-overworked health systems.

But, in Nigeria, many women of reproductive age had difficulty gaining access to family planning services, especially during the peak period. Asides the government-imposed restriction on movements and the general fear of contracting COVID-19, the situation was further complicated by a series of strikes.

About 150 resident doctors at the Ondo State University of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital (UNIMEDTH) had in January embarked on an indefinite strike over multiple months of salary arrears. Again, on June 23, the National Association of Government General Medical and Dental Practitioners in the state declared a strike over salary deductions and the special COVID-19 hazard allowance.

One industrial action by the National Association of Resident Doctors (NARD), in June, crippled operations at major facilities, including UNIMEDTH in Ondo town and Akure, the Federal Medical Centre in Owo, as well as General Hospitals in Ikare Akoko and Okitipupa.

Dolapo,* 26, a resident of Akure, had also started using the contraceptive injection of 13 weeks before the COVID-19 outbreak. She should have renewed in April but could not. Two months later, she discovered she had become pregnant. The couple, just a year and a half into their marriage, decided they could not keep the baby. So, Dolapo’s husband called a friend who took her to see a quack doctor.

“When the lockdown started, we were both asked to stay at home without pay. If we had some money, maybe we would even have gone to a private health facility to get the injectable contraceptive. But there was nothing,” she laments.

The abortion was conducted without complication but not everyone who attempted it was as lucky. This is because not only could women not benefit from contraceptive services, but the strike by health workers meant they could also not access post-abortion care at public health facilities.

According to Nigeria’s criminal and penal codes, any woman who tries to procure her own miscarriage or anyone who assists her is guilty of a felony and can be jailed. The courts have ruled that abortion is only legal if it is required to save the woman’s life. As a result, two to three million women resort to unsafe abortions every year. But it is highly dangerous.

WHO estimates that between 4.7 and 13.2 per cent of maternal deaths are as a result of unsafe abortion. In Nigeria, about 212,000 women were treated for complications arising from induced abortion in 2012. Some of the common complications include heavy bleeding, incomplete evacuation of the foetus, infection, uterine perforation, and damage to internal organs.

“Mentally too, it affects them,” suggests Lagos-based maternal health expert and nursing officer, Adebayo Olajumoke.

“There is a lot of guilt associated with abortion, especially when it is unsafe. There is a lot of trauma attached to it. This is also because the quacks don’t show a lot of empathy in providing the service to them.”

* * *

The lack of access to family planning services during the lockdown affected specific groups of women in different ways. Rape victims, for instance, became pregnant because they did not have emergency contraceptives, which generally should be taken within three days of intercourse.

Women living with HIV also have peculiar challenges taking the form of stigma and discrimination. Ejiro Joy, who works as a mentor mother with the Network of HIV Positives (NHIV) programme in Ondo, narrates the bitter experience of one of her clients.

“She had asked to access a family planning method of 10 years because she does not have a lot of free time. The nurse told her to go for an HIV test. She then said there was no need as she was already on antiretroviral drugs and knew her status,” Ejiro says.

“The woman then said she could not access the one of 10 years, but could have that of three months. She is not happy with this and says it was because she revealed her status. The way they talked to her changed and she could sense the stigma.”

* * *

The problems with access were visible nationwide. Adebayo observes that many Primary Health Centres were closed in Lagos during the lockdown. Some of their workers were also drafted into the frontline battle against the coronavirus pandemic at various isolation centres. Meanwhile, not all private health facilities provided family planning services and those that did often limited their intake to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The difficulty in getting contraceptives was compounded by the fact that a lot of women preferred health facilities farther from their residence. For some, this was because they had to leave for work early in the morning and get the services before returning home. For others, it was the only way they could get modern contraceptives without their partner or relatives finding out.

So what can be done to prevent restricted access to contraceptives in a country where prevalence rates are ordinarily below par?

“First of all, we should let everybody understand that family planning is an essential service that actually has a good effect on the economy,” Adebayo proposes.

“At any time, including during emergencies, women’s health issues are always essential services. Always, always. I think by the time we put that in mind, we won’t have a case of shutting down everywhere because there is a pandemic.”

Indeed, according to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), if Nigeria reaches a contraceptive prevalence rate of 36 per cent, it could save 121,000 lives of mothers and children within three years. Additionally, increasing the rate by 2 per cent each year could save the country N6.9 trillion in primary education costs and the need to create 19 million jobs between 2017 and 2050.

Oluwapelumi Alesinloye-King, the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) country consultant for Women First Digital (WFD), has seen first-hand how unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortion affect women in Nigeria. Asides damages to vital organs, infections, becoming infertile and a host of other side effects, she has seen cases of women having suicidal thoughts because of the horror of the unsafe process they went through.

“We have girls who tried to jump from top floors, hoping that would terminate the pregnancy,” she recounts. “We have situations where they used crude materials such as cassava stems and iron hangers to initiate the process of abortion.”

There are lifelong physical and psychological consequences due to the inability to access safe abortion methods and post-abortion services, she says.

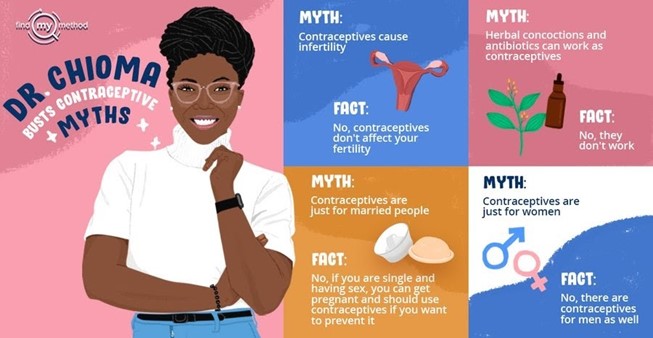

Her organisation, WFD, runs three digital platforms to improve access to reproductive health services for women: Find My Method, Safe2Choose, and Pink Shoes.

FindMyMethod tries to provide accurate information on contraception tailor-made to the individual’s preferences as well as referrals to youth-friendly locations to get contraception. Safe2Choose provides information on different forms of safe abortion methods and counselling services for women who have unwanted pregnancies without requiring that they reveal their identities. It also refers people to reliable healthcare providers. Pink Shoes, on the other hand, provides information on medical abortion pills and post-abortion care.

“We have realised that so many people have wrong, corrupted information and the only way to counter this is by creating platforms that provide the correct information as well as referrals to needed services,” says Alesinloye-King.

“One thing about these platforms is that they are at your fingertips. You can access them from the comfort of your house and learn about contraceptives that suit your lifestyle, age, and pocket.”

WFD works with influencers across different states to put out localised contents about family planning and reproductive rights. To further reach people from various backgrounds, information on the three platforms have been translated and made available in English, Yoruba, Nigerian Pidgin, and Hausa.

But the work of social enterprises like WFD is not enough. Alesinloye-King believes there is still a lot left for the government to do. It can start, for instance, by decriminalising abortion as this automatically reduces the number of women who seek out quack providers.

“This means they are able to visit a health facility and get the all-round information and care they need. They will also be able to get a safe method of abortion especially according to the age of gestation and preexisting medical conditions,” she explains.

It also means quack providers such as traditional birth attendants, chemists, and auxiliary nurses can be trained on the different methods of abortion and how to manage the process successfully. The government can additionally help reduce the rate of unsafe abortions, she adds, by improving access to affordable contraception, post-abortion care, as well as encouraging comprehensive sexuality education at all levels.

Iwatutu Joyce Adewole, Program Lead at the African Girl Child Development and Support Initiative, chips in that policy changes are also necessary, especially in improving access for adolescents. Though existing documents do not outrightly prohibit access to reproductive health services for young and unmarried girls, implementing groups often assume they need parental consent. Adewole maintains that the policies have to be explicit and specific.

Back in Akure, Ondo State, Omolara has renewed her contraceptive since the lockdown was relaxed in May.

She was asked to buy and come with certain items, including nose masks, tissue paper, injection, and gloves, but wonders why they did not just make those demands earlier. “Since they know those are the things we needed, if the hospital had been open, we would have bought them and done what we needed to do,” she protests.

“They should let the hospital be open to everybody at any time, especially us women. One can have emergencies at any time. We cannot say we will not have sex or fun because of the risk of getting pregnant.”

*Pseudonyms are used to protect the women from stigma and criminal charges

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter