How Climate Change Is Undermining Peace And Security In Nigeria

In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned global policymakers of the need to cut emissions by 45% before 2030 to restrict global warming to 1.5°C. Although a rise above 1.5°C is the point where the consequence of global warming are expected to become increasingly severe and more difficult and expensive to mitigate, the world is already witnessing catastrophic natural disasters such as record-breaking high temperatures, extreme wildfires, melting glaciers, flooding and drought.

Despite the country’s low contribution to greenhouse gas emission and global warming, Nigeria is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change-related extreme weather conditions and natural disasters. The impacts are exacerbated by rapid population growth, a fragile economy, high dependence on rainfed agriculture and the country’s weak adaptive capacity.

Unseasonal and high temperatures and rainfalls, severe flooding and desertification are overlapping with socioeconomic stressors to further deteriorate livelihoods, economic opportunities and increase competition over natural and environmental resources, which in turn has amplified social tension and a vicious cycle of conflicts.

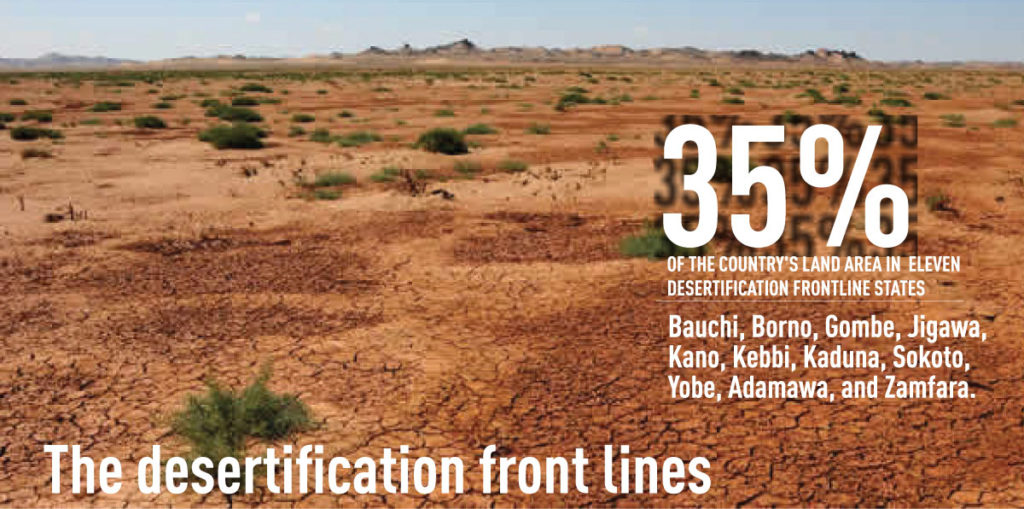

The desertification front lines

Northern Nigeria has a tradition of, mostly, Fulani cattle herders migrating across the lush grasslands and savannahs. However, this movement of people and livestock has taken a deadly turn in the last decade with violent conflicts between herders and farming communi t ies an increas ingly common occurrence. A lot has been written about the violent at tacks on farming and herder communities in the middle-belt, but not so much about the situation in the north-west.

Northern Nigeria has a tradition of, mostly, Fulani cattle herders migrating across the lush grasslands and savannahs. However, this movement of people and livestock has taken a deadly turn in the last decade with violent conflicts between herders and farming communi t ies an increas ingly common occurrence. A lot has been written about the violent at tacks on farming and herder communities in the middle-belt, but not so much about the situation in the north-west.

According to the International Crisis Group, the conflict between Hausa farmers and Fulani herders in the region has killed at least 8,000 people since 2011 and displaced more than 200,000 into the neighbouring Niger Republic.

Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Environment says desertification, worsened by the dual impact of climate change and unsustainable human activities such as overgrazing and tree felling for fuel and farming, is threatening 35% of the country’s land area in eleven desertification frontline states – Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Kebbi, Kaduna, Sokoto, Yobe, Adamawa, and Zamfara. With the impacts contributing to migration and conflicts over dwindling resources.

Weak governance and an overburdened justice system are also contributing to the violence. The region is awash with undocumented small arms which are used not only by criminals but the multiple militias and vigilante groups that operate in an envi ronment where law enforcement i s weak or non-exi stent. Kidnappings, looting, rape and arson happen regularly – as do revenge killings.

On 6 June, farmers cultivating their farmlands in Yar Gamji village, Batsari Local Government Area (LGA), Katsina State, were attacked by a group of nomadic herder allied mili tants on motorcycles. At least 30 people were killed in the incident. These violent crimes have undermined peace efforts, but violent clashes are also being sustained by a lack of alternative livelihood opportunities for young herders and farmers due to educational deficits and the growing impact of climate change.

Climate change, poverty and conflict are intertwined in the Lake Chad region. Although Borno State, the epicentre of the decade-long Boko Haram insurgency, was excluded from the National Bureau of Statistics 2019 report on poverty and living standards due to security concerns that made data collection unfeasible, Adamawa and Yobe states were ranked among the poorest states in the report. The region also bears the brunt of increasing temperatures and erratic rainfall which is having an impact on agriculture.

Desertification and the historical decline of Lake Chad and its wetlands have also impacted the local economy negatively. Although the lake itself has grown to 14,00 square kilometres in the past two decades and remains relatively stable in its southern pool, it is still recovering from a period of severe drought in the 1970s and 1980s when it shrunk from 25,000 square kilometres to just 2,000. The increased economic vulnerability of these communities has made young people more susceptible to being recruited to Boko Haram and its splinter group the Islamic State in West Africa.

A green wall?

In September 2019, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari announced plans to build a climate – resilient future and committed Nigeria to fulfil its Nationally Determined Contributions made under the Paris Agreement to reduce national emissions. Key aspects of the country’s resilient future plan are the development of a green wall shelterbelt, the introduction of climate-smart agriculture practices and a commitment to Lake Chad ecological restoration.

The green wall, covering 1500 km from Arewa Dandi LGA, Kebbi State to Abadam LGA, Borno State is designed to restore degraded land, improve the availability of environmental resources and contribute to the country’s carbon capture and storage. Conditions that will improve livelihood opportunities and that can go some way to addressing the perennial violence between nomadic herders and farming communities. This was also part of the thinking behind the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development’s unveiling, in June 2019, of plans to create rural grazing area (RUGA) settlements.

The Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria – the most organised and influential herder advocacy group – endorsed the plan to settle herders and their cattle herds in an organised environment with adequate basic amenities. The settlements are to provide schools, veterinary clinics, mini ruminant feed mills, water points, grazing land and manufacturing entities that will process and add value to by-products. Despite the suspension of the federal RUGA plan in July 2019 – after resistance from many states and a public backlash over fears that its true motive was a land grab by influential politicians to favour the Fulani ethnic group – two states have pressed ahead with their own plans.

In Niger State, about 30,000 hectares of land in Bobi Grazing Reserve in LGA has been set aside. While in Zamfara, the government is investing in RUGA settlements in Maradun LGA as part of its ‘soft approach’ to ending the violence. It remains too early to comment on whether the approach is having a discernible impact.

For farmers, under pressure from unpredictable weather conditions, access to timely weather information will improve crop production and is one part of the government’s effort to introduce climate-smart agriculture practices. Crop diversification, including using more drought resilient crops, and redesigns to farmland to maximize productivity and protect the soil in the face of increasingly severe and frequent droughts are also being supported.

In north-eastern Nigeria, the United Nations Food and Agr icul ture Organizat ion, in partnership with the government, is promoting the adoption of climate smart agriculture techniques in conflict-affected states of Adamawa, Borno and Yobe to make livelihoods of farmers more sustainable in the face of changing climate. However, greater private sector and government investment is required to improve access to modern farming innovations.

Finally, the Lake Chad Replenishment project, an ambitious inter-basin water transfer proposal to channel waterfrom the Ubangi river in the Democratic Republic of Congo to the Chari River system that feeds Lake Chad, is expected to protect the lake from some of the effects of climate change. This, in turn, should keep local industries buoyant and address some of the wider socio-economic enablers of conflict in the region. But the replenishment project runs contrary to recent hydrological findings that suggested the lake is not actually shrinking. It also fails to put sufficient emphasis on addressing decades of poor governance and

Finally, the Lake Chad Replenishment project, an ambitious inter-basin water transfer proposal to channel waterfrom the Ubangi river in the Democratic Republic of Congo to the Chari River system that feeds Lake Chad, is expected to protect the lake from some of the effects of climate change. This, in turn, should keep local industries buoyant and address some of the wider socio-economic enablers of conflict in the region. But the replenishment project runs contrary to recent hydrological findings that suggested the lake is not actually shrinking. It also fails to put sufficient emphasis on addressing decades of poor governance and

resource accessibility challenges around the water source.

For now, the negative effects of climate change, environmental degradation and weak governance will continue to increase the risk of conflicts, while exacerbating existing ones. Only with more sustainable, climate-sensitive development and environmental management can the limited natural resources, a driver of various conflicts, be preserved. Doing so will offer more fertile ground on which peace and security can be built.

This report was originally published by the Centre for Democracy and Development.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter