Gender Roles Are Resulting In Lowered Qualities Of Life For Nigerian Women

Care jobs such as housework and child-rearing are considered women’s duties in many parts of the country due to women’s assumed ‘biologically wired nurturing and homemaking’ abilities. But these societal norms and gender roles are costing women their mental, professional, and social health.

As the only female child, Deborah John’s* extra responsibilities started so early that they felt natural.

Often, she was forced to stay back in her mom’s shop while her brothers got to spend their time on hobbies like football.

“I wasn’t allowed to go out and play, and I was the only one who was taught how to cook and clean, fetch water, and all of that, and that didn’t allow me to have room for a lot of female friends because I also had things to take care of after school such as going to my mum’s shop.”

Deborah started working in the shop when she was 14 years old. All she had to keep her company were her books. She has memories of being left behind in her mom’s shop until around 8:00 p.m.

“My mother works, so I am usually forced to stay back till she closes work and comes to pick me up before we go home together.”

Her responsibilities then included attending to customers, taking account, and other related tasks, but none of them relieved her from the responsibilities in the house despite having an older and younger brother.

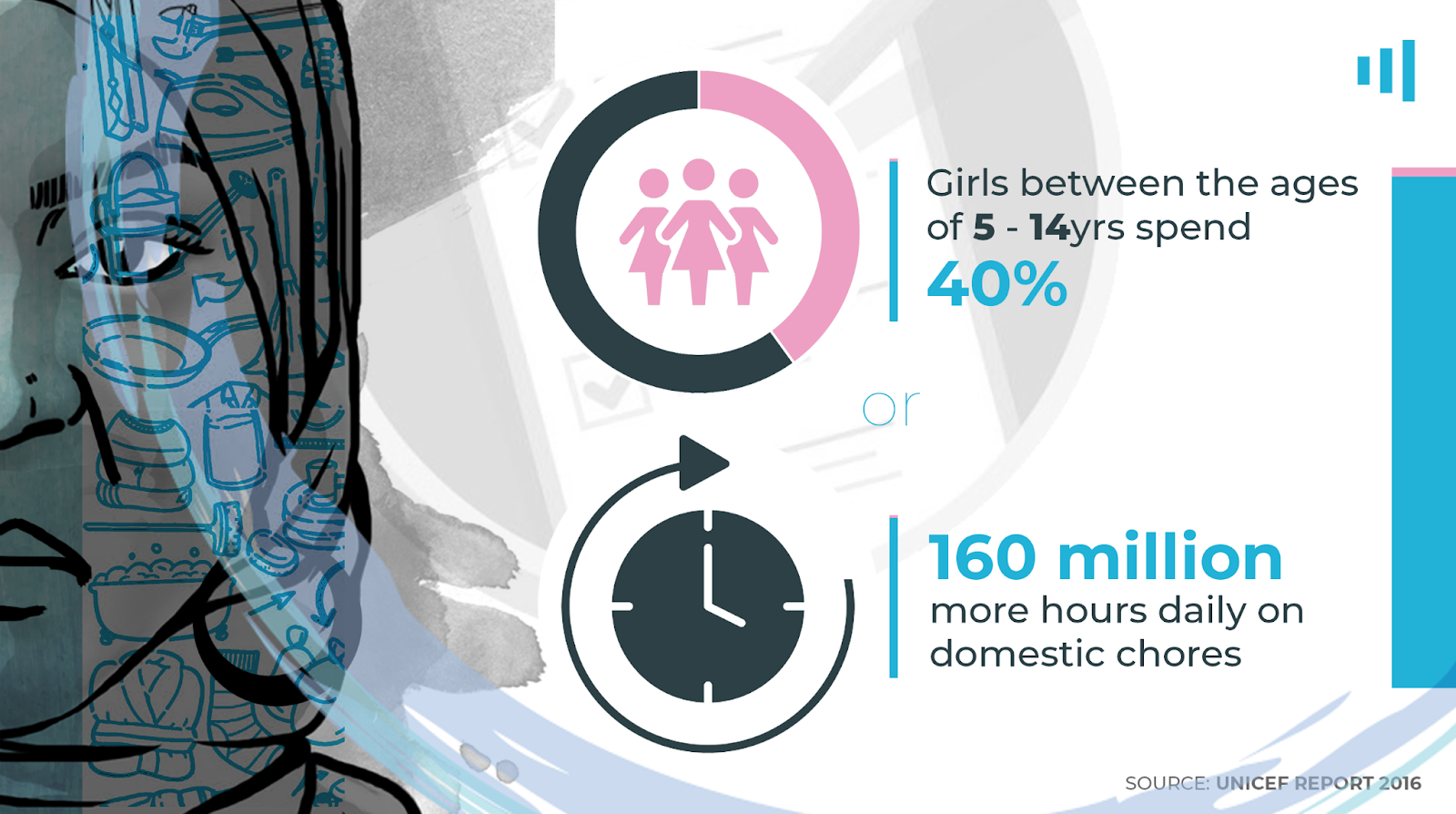

A UNICEF report released in 2016 states that girls between the ages of 5 and 14 spend 40 per cent more time or 160 million more hours daily on domestic labour than their male counterparts, and this labour is often undervalued.

The report also shows that in some countries, fetching water and getting firewood leaves young girls at risk of sexual violence. This disparity impacts their education and future employment prospects, denying them the time to study, socialise, play, and simply be children.

According to Anju Malhotra, UNICEF’s Principal Gender Advisor, the disproportionate burden of household work worsens when girls become adolescents. “As a result, girls sacrifice important opportunities to learn, grow, and just enjoy their childhood. This unequal labour among children also perpetuates gender stereotypes and the double burden on women and girls across generations.”

One of the biggest impacts of this culture on Deborah was in the way she found it difficult to engage with others, especially fellow women, even as an adult. She felt robbed of her time. The time she could have used to develop herself, find new hobbies, and cultivate friendships as a child was spent for the family’s sake alone.

“I feel like I have come to resent gender roles. My experiences made me crave independence and I said to myself, I won’t do that for any man again.” She finds it easier to cook for other women — “I despise cooking for men; in fact, I only date men who know how to cook. I cannot tolerate a lazy man or someone who thinks it’s a woman’s duty to cook and clean.”

She still hates Christmas because she has come to associate the festive season with spending nearly the entire day preparing various meals and doing chores.

Decline in studies

Deborah wasn’t allowed to stay in the hostel during her university days because they needed someone to stay back and do the chores, and that affected her studies. “While my friends were reading and thriving, I was busy shuttling between school and the house, cooking and taking care of the house.”

It started to get really bad, and she noticed that her studies were suffering, especially after she almost withdrew from school due to the stress and having little or no time to read. She found a way to move out in her third year of university.

“I had to forego the benefits I was getting from my family and move into the hostel.” Because of that decision, they stopped taking care of her needs, and she was forced to start fending for herself. This, however, provided her with the opportunity to spend more time on herself and her needs.

Deborah still feels resentful, and she believes the whole experience put a strain on her relationship with her family, especially between her and her mother.

She thinks the only good thing that came out of her experience is that it made her more conscious of the men she allowed into her life.

A job deferred

Growing up, Sarah Mathew* wasn’t really aware of gender roles because, for a long time, it was just her and her father, and they had people who worked for them. Her only duty then was to go to the market.

But down the line, things changed when they started living together as a family with her mother and brothers.

“Once, we ran out of water on a Saturday morning, and my sibling was home for a brief holiday. My parents and I went out, and he stayed back home. We came back to meet the pile of plates we had left waiting for us. He claimed he didn’t realise we had left water in the bucket. Even though my dad insisted he should have made more effort, my mum dismissed it and said not to bother the man as I would wash them.”

By that time, Sarah had started to take responsibility for the chores even when she started working. “I begged that we find a help, but nothing was done about it. I was expected to sacrifice my time, and so I would go home every day in the afternoon from work to make lunch.”

To make matters worse, Sarah tried to reason with her bosses so they could say no to her going back to do house chores during work hours, but they thought it was okay and an important sacrifice to make as a woman. “They saw it through the lenses of men being expected to be providers, and because it’s been that way for ages, women should be okay with making certain sacrifices.”

Under a patriarchal system, men are assumed to be the dominant ones, and women are made to take subordinate roles, and this leads to the oppression, exploitation and domination of women. This leads to men having more freedom and women being more restricted.

The unequal value system is pervasive across Nigeria’s social classes. In 2016, former President Muhammadu Buhari infamously said his wife, the First Lady, belonged to his kitchen, living room, and “the other room” in response to criticism from her. Even though there was outrage on social media, many Nigerians from both genders believed that such comments were justified.

Looking back, Sarah felt like she should have stood her ground, maybe then she “wouldn’t have felt so uncomfortable and unmotivated”.

Sarah did the shuttling between work and home for three to four months. Most times, she would find herself ranting and criticising herself on the way due to the mental and physical strain, and that was one of the main reasons she eventually quit her job.

Unpaid labour largely contributes to the quality of work that women produce and determines whether they even get to enter or stay in paid employment. It also affects their health.

A study done by a team of researchers from the University of Melbourne shows that women across the world are at higher risk of developing poorer mental health than men due to the unequal division of unpaid labour. Housework stress affects women more than it affects men, and a US study states that inequality in the division of household labour contributes to sex differences in cases of depression.

Another study shows that even though women report a decrease in their physical health when they work high hours in both their jobs and homes, they also report a decline in their health when they believe they have done less than their fair share of household chores. This is said to be linked to feelings of empathy and guilt towards their partners.

Because Sarah didn’t grow up doing house chores, it was hard for her to adjust to this new reality. “A lot of times, I have just been expected to know stuff because I am a woman. I am close to being clueless in the kitchen. I can do the small stuff that one can survive on, but I can’t do the big stuff.”

But she has been told many times that men won’t settle, and she needs to understand, practise and learn those things.

In Nigeria, women for a long time have been restricted to domestic activities, and this belief was further built on during the colonial period when girls were mostly taught domestic skills while boys were taught clerical skills. Sociologists have identified combined paid and domestic labour as a factor that further pushes inequalities between men and women, also infringing on women’s lifestyle, social life and time.

Studies also show that women are more likely to experience negative employment trends such as absenteeism, inability to continue their jobs, geographical immobility, restriction in the number of work hours, and frequent work interruptions.

A homemaker’s dilemma

Habiba Usman’s* upbringing was full of contradictions. Her stepfather did most of the housework because her mother worked a lot.

“He cooked and took us to school. On the other hand, things were different with my biological father. He was the provider, and his wives don’t even go out without his permission.” When there is no driver, he prefers to drive them wherever they are going and will sometimes even prefer to run the errands himself than let them go out.

“When it came to chores, I didn’t have to do anything with my mum being a full career woman who contributed to decision-making in the house and had the freedom to do what she wanted.” Since she spends most of her time with that part of the family, it has heavily influenced her life.

Her introduction to gender roles came with marriage. Her husband is “incredibly traditional” and has never attempted to do any work in the house, even when she is overwhelmed, she says. “The only compromise we had was for me to get a domestic help.”

It is overwhelming for Habiba to work remotely, be the nurturer and also take care of the home while her husband gets to do what he likes with his own life.

One theory that has fueled gender roles for centuries is the belief that throughout human history, men were hunters and women were gatherers, therefore making it natural for men to be providers and women to take on more homemaking and nurturing roles which left room for blind spots in scientific research.

However, recent research by Cara Wall-Scheffler, a biological anthropologist, and her team has uncovered that men were not exclusively hunters and women have been hunting alongside men. In fact, women were hunters in 79 per cent of the societies with available data. According to Cara, “the hunting was purposeful. Women had their own toolkit. They had favourite weapons. Grandmas were the best hunters of the village.”

Unfulfilled career dreams

When it comes to opportunities that will impact her life and career, Habiba’s options and choices are very limited. “I don’t get to travel for opportunities because my husband isn’t usually around, and even if he is, he doesn’t let me travel alone unless it’s with someone he really trusts.”

Habiba says her marriage is everything she had expected and wanted, apart from the limitations it brings her.

“Things changed when the baby came, and getting a help is not a steady solution because sometimes they have to leave and that in-between time can drive you crazy.” With a two-year-old baby, her hands are full.

“Having a child changes everything; many things are put on hold because you are the primary caregiver. I do everything child-related; there is no break or help to accommodate what I want. And I am constantly worrying because if I am not the one that does it, nobody does.”

Even without the limitations placed on her travelling, Habiba believes it would be unfair or insensitive for her to travel and leave her husband when he comes back home. In some cases, it is just not feasible for her to travel with her son, and she cannot leave him alone with his father.

As a data entry expert, opportunities to give training to staff and gigs to do inventory management or software installations can come up, and most of these opportunities tend to be outside Kaduna state, North West Nigeria, where she is based. But gender roles covering household chores and expectations of her as a married woman prevent her from taking these opportunities.

For women who combine household care with full-time career jobs, research shows that unpaid work does not reduce as they go into paid employment. They just tend to work more hours, which means that overall, men do not work as much as women do.

Societal implications

As a second child in a family of five children, household chores were shared equally among Zainab Yahya* and her siblings growing up, regardless of gender. Chores were rotated, and because of that, her childhood didn’t suffer. “We were allowed the same kind of aspirations,” she told HumAngle.

Zainab’s earliest memory of the societal implications of gender roles was in university. One time, when they were planning a department event which she volunteered for, she was willing to take part in the planning, logistics and general administration, but she was automatically assigned to the food committee.

“I was like, hold on, food is cool, but that’s not my strong suit. I got the committee changed, but it was something that stood out at the time for me because of how subtle, yet clear the stereotyping was.” Even though the transition wasn’t dragged out, Zainab believed she got the usual ‘let’s avoid this feminist wahala’ reaction from other committee members.

According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, gender stereotyping, even when they are benign, such as the belief that women are nurturing by nature, helps in promoting inequalities. This stereotyping affects things such as freedom of expression, freedom of representation and political participation, right to work and even freedom from gender-based violence.

This kind of belief can also trap women into traditional roles and make these responsibilities fall strictly on their shoulders.

Katherine .B. Coffman, a Harvard Business School Assistant Professor, found in a study that gender stereotypes change not only how women view themselves but how society views women and by buying into those stereotypes, women create a bleak self-image of themselves that is likely to set them back professionally.

Zainab witnessed both social and biological implications of gender roles in her life.

“I am a new mother at the moment, taking a career break by my own choice to take care of my baby. But beyond doing it by choice, biology is playing a huge role as the baby’s father can’t obviously feed the baby because his body can’t produce milk or experience the toll pregnancy takes on one’s body.”

Even though she is expected to cook, clean, and take care of the baby and the house while her husband is expected to work and provide, the arrangement she has in her marriage is more flexible.

“These are not cast-in-stone arrangements. I do most of the cooking. We have a house help that does the cleaning. I don’t do a 9-5 now, so I am with the baby most of the day, but when my partner returns, he deals with her until she needs to be fed or needs a bath.”

Even though this flexibility is possible within their household, it isn’t always possible when they are in public spaces, such as holidays at his family home, due to societal expectations, and this leaves her feeling overwhelmed sometimes.

SEO:

Meta: Gender roles are costing women their mental, professional, and social health.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter