Gang Violence Traps Minna in a Cycle of Bloodshed

In Minna, North Central Nigeria, organised youth cliques known locally as Yan Daba have turned the metropolis into a hotspot for violent neighbourhood attacks, escalating into full-blown communal clashes with tragic outcomes.

The day after Eid al-Fitr, a festive period for Muslims, is usually quiet; a time for rest, reflection, and recovery for most tailors who had had sleepless nights to ensure people looked colourful during the celebrations. For Abubakar Ibrahim, this March, it became a day etched in trauma.

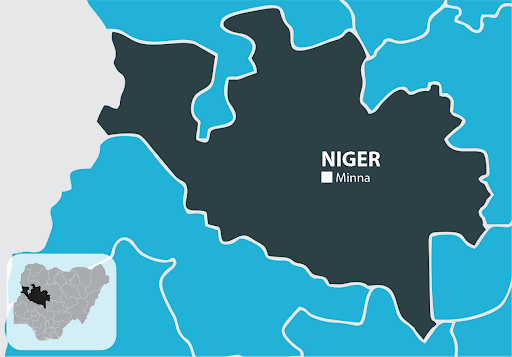

It began as a brawl between two boys from neighbouring communities, Tunga Sabon Titi and Maje, divided only by a narrow stretch of road in Minna, the capital of Niger State in North Central Nigeria. The brawl quickly escalated into a full-blown gang clash, drawing in allies and sympathisers from both sides.

Ibrahim, a tailor and student in his early twenties, was at home when the commotion began. “I was heading somewhere when I heard the rants ‘karya ne wallahi, Ba sulhu [It’s a lie, no reconciliation]’,” he recalled. “While all this was happening, vigilantes were trying to disperse the crowd as we stood and watched.”

Moments later, gunfire shattered the air. He never saw it coming; six pellets from a Dane gun tore into him. Two lodged near his clavicle, the rest in his lap. “I didn’t realise I was hit until someone drew my attention while we were running,” he told HumAngle. “Then I felt dizzy, my leg went numb, and I collapsed.”

Residents told HumAngle that Mada, a local vigilante, had been aiming at the gang when his bullet missed and struck Ibrahim, who had no part in the clash or any gang activity. He was simply trying to earn a living, yet became another innocent casualty in a pattern of violence that has become disturbingly familiar in Minna.

Tracing the origins

Investigations by HumAngle trace the roots of Minna’s gang violence to long-standing turf rivalries between youths in neighbourhoods in the mid-2000s, when loosely organised gangs, locally called Yan Daba, engaged in sporadic confrontations, largely confined to street-level disputes.

Over time, the scale and lethality of these conflicts grew. Neighbourhood rivalries now pit entire communities such as Limawa, Unguwan Daji, Bosso, Soje, Kpakungu, Barikin Sale, against each other. Festive periods, school closures, and political transitions frequently trigger violent episodes, often leaving deaths, injuries, and property destruction in their wake. Some sources within these communities said the violence sometimes happens as weekend fights over petty theft, insults, or territory.

These confrontations have also spilt into schools, with rivals asserting dominance through violence. Schools such as Zarumai Model in Bosso, Government Day Secondary School in Unguwan Daji, Father O’Connell Science College (formerly Government Secondary School), and Hill Top Model Schools have all witnessed inter-school violent gang clashes, sometimes ending in serious injuries or deaths.

HumAngle has previously documented the activities of a gang with the same name in northwestern Nigeria’s Kano, where they terrorised neighbourhoods, showing that this style of youth-driven violence is not confined to one city.

These gangs are usually armed with daggers, cutlasses, and sharp weapons like scissors, animal horns, and screwdrivers.

This violence is not confined to the past. In a pre-dawn sting operation in April, police officers in Niger State arrested 24 suspected criminals linked to thuggery and armed robbery in Maitumbi, a troubled suburb of Minna. The coordinated raid, led by the Anti-Thuggery Unit and backed by local police divisions and vigilantes, targeted crime hotspots like Angwan-Roka, Kwari-Berger, Flamingo, and Tudun Wada, following a surge in youth violence and gang activity, according to police spokesperson Wasiu Abiodun.

In March, the state Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education shut down Government Day Secondary School, Bosso Road, and Father O’Connell Science College in Minna, after assessing ongoing conflicts between students and local youths, some posing as students.

Although many incidents go unreported, they continue to claim lives and property.

In April last year, a violent clash between rival gangs in the Maitumbi area left two dead, with shops, vehicles, and tricycles damaged. The police confirmed the arrest of six suspects connected to the incident and stated that efforts were underway to apprehend others involved.

Later in December, a 15-year-old boy, Saidu Ubu, was killed in another fight between rival groups from Gurgudu and Kwari-Berger. The altercation, which began as a minor dispute late at night, quickly escalated into a brutal fight that caused panic among residents. By the time police arrived, the attackers had fled.

More recently, police arrested 18-year-old Jamilu Abdullahi, known as Zabo, over alleged armed robbery, culpable homicide, and gang violence in several of the affected communities.

Caught in the fix

For residents like Ibrahim, these flare-ups are more than news headlines; they are life-altering. After he collapsed due to the gunshots, his brother rushed to the scene and took him to Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida Specialist Hospital, a nearby public medical facility.

But the ordeal was far from over.

When they arrived at the hospital, they were told that there were no doctors available to attend to him at the moment. “They only gave me some injections but didn’t attempt to remove the bullets,” Ibrahim recounted.

Four days later, still in pain, his family turned to a local hunter in nearby Wushishi known for removing Dane gun pellets. The hunter succeeded where the hospital had failed.

“I was unconscious when I arrived at the hospital,” Ibrahim said. “I only woke up there. But the bullets stayed in me for four days until they were removed by the local hunter.”

The recovery was slow and painful. Ibrahim missed his exams, adding academic loss to physical trauma. “It took me a while [over a month] to recover,” he said quietly.

The vigilante accused of shooting him was reportedly arrested, but Ibrahim has heard nothing since; no justice, no closure.

Residents who spoke to HumAngle expressed concerns over the lingering menace that has not only continued to affect their loved ones but has also left them worried about having to raise their children in such an environment.

“I do not want my child to grow up witnessing this violence and someday be influenced to partake in it. It will break my heart,” said Danlami Shittu, a designer whose shop is just metres away from where Ibrahim was shot. “Every festive period, we hold our breath. These boys do not just fight; they settle old scores. Yet those of us who are not involved still pay the price.”

The missing links

Aminu Muhammad, a consultant in peace and conflict management, said the roots of this crisis lie deep within the decay of societal values and systemic neglect and a defect in the state’s justice and security frameworks.

He identified poor parenting as a primary driver of youth delinquency in the city, noting that many parents in the city are disengaged from their children’s lives, unaware of where they live or who they associate with.

This parental neglect has created a vacuum filled by peer influence and street culture, pushing many youths toward gang affiliation. “You must first take care of your children before they become more acceptable in society,” he told HumAngle.

Beyond the home, Dr. Aminu, who is also a lecturer at the Abdullahi Kure University, Minna, revealed that lack of access to education and vocational training has left many young people idle and vulnerable. Those who cannot enrol in formal schools are rarely offered alternatives to learn trades or acquire skills that could make them self-reliant. This absence of opportunity often translates into frustration and a turn toward violence.

Dr. Aminu also points to the failure of security agencies and the justice system.

“When there are calls to security personnel during violent encounters, the response is often delayed. These delays allow attackers to escape and victims to retaliate, perpetuating a cycle of violence,” he added. “Even when arrests are made, the lack of stern punishment mechanisms undermines accountability. These guys are granted bail or discharged without much consequence. Influential persons and even government officials sometimes intervene to secure their release.”

To stem the tide of violence, the conflict management consultant suggested a multi-pronged approach: stronger parental involvement, public sensitisation through the National Orientation Agency, and a tougher security and judicial framework. Without this, he warns, Minna risks losing its identity as a peaceful city and its youth to the streets.

Bello Abdullahi, the state’s Commissioner for Homeland Security, did not respond to multiple calls and messages requesting official comments on the issue.

For Ibrahim, the physical wounds have healed, and he has returned to his tailoring, but the emotional scars will outlast the headlines. And for other casualties of this violence, their stories never even make it that far.

“I want peace. Not just for me, but for all of us,” Ibrahim said.

Minna, Nigeria faces escalating gang violence rooted in longstanding turf rivalries, which now pit entire communities against each other.

The violence, often spurred by petty disputes, has extended into schools, causing injuries and deaths. Local gangs, armed with knives and daggers, continue to pose a threat, despite police efforts to curb their activities.

The lack of prompt action by security forces exacerbates the situation, leaving communities in fear during festive periods when violence typically flares up.

The issues are compounded by systemic problems, such as poor parenting, lack of educational opportunities, and ineffective justice systems. Consultant Aminu Muhammad links youth delinquency to parental neglect and the absence of vocational training, which leave many young people idle and vulnerable to gang influence. He calls for stronger parental involvement, public awareness campaigns, and more effective security responses to restore peace in Minna.

Meanwhile, residents like tailor Abubakar Ibrahim, a victim of gang-related violence, call for an end to the chaos that disrupts daily life and safety.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter