From Elephants to Warthogs: The Shadow Wildlife Trade Financing Boko Haram in Nigeria

As elephants vanish from Nigeria’s conflict-affected northeast, poachers and terrorists turn to warthogs—an overlooked species with tusks just as valuable. With little regulation and growing global demand, warthog ivory is now fuelling a new black market. At the heart of it lies a deadly trade financing terror and deepening regional instability.

Under a tea seller’s makeshift shade in the Molai community in Borno State, North East Nigeria, three men sat closely together in mid-December of 2024, dressed like herders—jackets pulled over faded kaftans, straw hats over turbans, and herding sticks resting beside each. They looked to be in their late 20s, conversing calmly. Suddenly, one of them, who had been carefully observing the horizon, rose and attempted to dash.

Just then, armed men of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) and the Nigeria Forest Security Services (NFSS) emerged from behind market stalls and nabbed them. A slightly blood-stained sack lay beside them. They had come, covertly, to trade poached wild animals, Saddam Mustapha*, an officer of the NFSS, said. The three men were from Kawuri, a village in the Konduga Local Government Area (LGA) of the state and close to the Sambisa Forest. The team had earlier received intel about this and lay in an ambush that morning.

However, it was not the illegal wildlife trade that triggered the arrest. Molai, after all, has become an open market for bushmeat. The men were suspected middlemen of the Boko Haram terror group, Saddam said, and had come to help sell these animals for the terrorists. Before further questions could be asked, Saddam recalls, military men of the team blindfolded and took them to the Maimalari military facility in the state. Efforts to get comments from the Theatre Command’s Headquarters, Operation Hadin Kai, in Maiduguri were unsuccessful.

In the days that followed, whispers of the arrest swept through Molai. Many were puzzled—everyone knew the men had come to sell warthogs, and as far as they knew, that was no crime.

But a few knew there was more to this bounty than just meat. Beneath the tough hide and coarse bristles lay something coveted: the curved ivory of the warthog. Dealers and traders, operating quietly and with discretion, collect them. Many hunters do not even understand why this is the case. But for those who do, these tusks are a poor man’s substitute for elephant ivory—smaller, yes, but similar enough in composition to fetch value in black markets.

The Sambisa Forest was home to a large population of elephants. For years, hunters and local poachers roamed freely, capturing them for their tusks. As the Boko Haram insurgency worsened and the poachers grew bolder under the cover of conflict, their numbers dwindled. “We used to see them often when we wandered into the forest as boys,” recalled 65-year-old Mohammed Tela, a resident of Pulka, a village in Gwoza, close to the forest. “You could hear their trumpets at night while you slept,” added Ba Wakil, a 50-year-old vigilante and member of a local patrol from Nguro Soye, another village on the forest’s edge in Bama. “But after the fighting began, they migrated into Cameroon.”

Conservator-General of Nigeria’s National Park Service (NPS), Ibrahim Musa Goni, confirms this during an interview with HumAngle, saying: “The density of the forests has reduced. The population of animals has also reduced. This is largely due to the activities of loggers and, in some cases, insurgents.”

With the elephants gone, the focus shifted. Local hunters, pushed by survival, and insurgents, drawn by profit, began targeting a different animal. Warthogs—once overlooked and hunted mostly for meat—suddenly became valuable. Their tusks, smaller but dense and curved, made of the same dentin as elephant ivory, began to follow the same smuggling paths. They slipped into the region’s underground markets, with their worth growing gradually.

In the void left by vanishing elephants, a new trade emerged. Now, a shadow economy, shaped by conflict, thrives in the ivory of warthogs, among other wildlife animals in the forest.

The shift from elephants to warthogs

Saddam, himself a hunter, recalls his grandfather, Mai Durma, hunting these mammals in those areas. “When my grandfather was hunting, they sedated their bullets with a special herb. This weakens the animal. When it falls, his team would butcher it on-site while he takes away the tusk.”

Wakil remembers that the tusks, removed in the forest, were transported covertly using donkey carts, motorcycles, or hidden compartments in vehicles heading to Maiduguri.

As far back as Saddam can remember, his grandfather, the village head of Durmari in Konduga and then the state’s hunters’ leader, would be visited at home by “white men.” “When they came, he would give them the tusks. My mother used to say he gave them away freely, as artefacts.”

“The elephants are not easily hunted, and not by just anyone,” said 75-year-old Alhaji Lawan Adamu, a licensed ivory and wildlife parts dealer in Maiduguri. “The [Borno State] Ministry [of Environment] often carries out a ‘control’ operation, meant to prevent herds from straying into residential areas or farms. Rangers would shoot one or two to scare the rest. The ones shot would be butchered, and the tusks auctioned to us.”

The ministry also auctions off seized ivory shipments entering from Cameroon and the Central African Republic. “We are then given a ‘predisposal permit,’” said Lawan-Adamu. “The permit records three people: the buyer, their buyer, and the next. It is all an effort to show the legality of the trade.”

Before the insurgency, a kilogramme of elephant ivory sold for ₦100,000 ($62) to ₦200,000 ($125) depending on quality and demand, Lawan-Adamu recalls. While licensed transactions were done in public, others occurred in secrecy.

Unlike Lawan-Adamu, who transported his goods openly, unlicensed traders had to conceal theirs. Adamu Yakubu Wanzam, a local fixer familiar with the trade, explained that ivory would be hidden inside shipments of dried fish, beans, or cowhide. “You would see a truck of beans and not suspect a thing,” he said. “But inside, there might be tusks—sometimes sewn into thick hides or tied beneath the vehicle.”

From Maiduguri, the tusks made their way to Kano or Lagos. “I would transport mine to Lagos to sell to the Chinese and Koreans,” Lawan-Adamu said. “We have a contact person there who links us to these Asians. We offload at his depot. He also has a Gambian partner who sells white ivory. We’re paid in U.S. dollars—between $5,000 and $10,000 depending on the size, type, and purity of the tusks.”

But as the Boko Haram insurgency entrenched itself and spread across Borno’s forested regions, the dynamics of the ivory trade shifted dramatically. Armed groups occupied critical elephant habitats like Sambisa, transforming them into fortified strongholds. The conflict, coupled with indiscriminate hunting, led to a drastic reduction in elephant sightings.

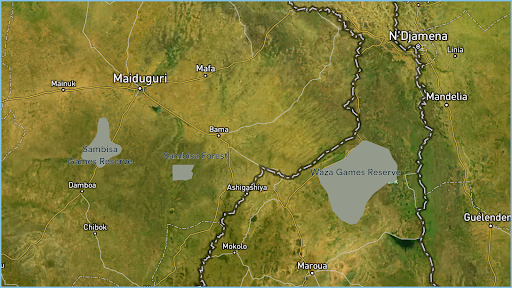

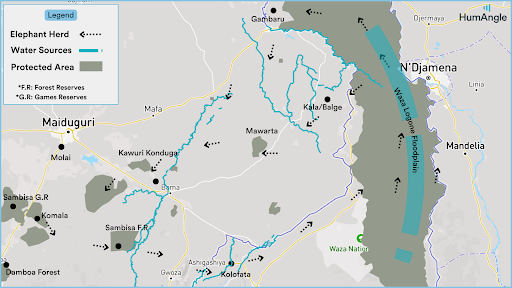

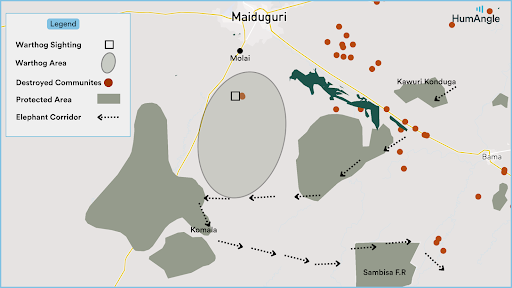

“The elephants from Sambisa used to migrate through Komala Forest, their main route, passing through Masafanari in Konduga on their way to Cameroon,” said Saddam. He has tracked games since he was 15. And as a member of the NFSS and part of the RSS team, he patrols the region’s forested areas frequently. “The herds often stop to drink from the River Kadua in Konduga,” he added.

A HumAngle Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, corroborated by sighting reports, indicates that while there may no longer be an elephant domicile in Sambisa Forest due to insurgency, movement toward Cameroon’s forests, and intensified poaching, elephants still occasionally pass through the forest in search of food and, more critically, water. This transient presence continues to expose them to attacks by poachers and terrorists in these ungoverned areas.

Recent local patrols also suggest significant elephant breeding is occurring in northern Cameroon. Wakil has sighted these herds while on patrol in the Bama axis of the forest, leading to Cameroon. Although they have now largely settled in Cameroon’s national forests, particularly the Waza Forest, a major wildlife sanctuary in the region, additional sighting reports show that about 200 or more elephants, forming a herd, still traverse the Sambisa Forest area.

“After crossing into Cameroon, the elephants usually continue deeper into Kolofata Forest,” Saddam explained.

GIS analysis of sighting reports, water sources, and habitat corridors shows that the herd’s migration path is circular, tracking a north-south trail of water sources as the dry season depletes surface water. They return north to Cameroon with the onset of the rainy season and repeat this cycle with each passing year. This corridor connects Nigeria’s Chad Basin National Park (in Borno and Yobe states, roughly 100–150 km north of Sambisa) to Cameroon’s Waza National Park. The path includes savanna woodlands and fragmented forests, with elephants following water sources like the Borno rivers and the wetlands around Lake Chad.

With elephant populations killed and heavily armed poaching syndicates losing a lucrative income stream, attention quickly turned to the next available source: warthogs. Despite being common across Borno, warthogs—and pigs in general—are considered haram (forbidden) by the state’s predominantly Muslim population and are not eaten in most communities.

“Hunters, including us, capture them almost every day. We sell them for the meat,” said Saddam. “They are freely and widely sold at Molai,” added Lawan-Adamu. “A fully grown warthog can fetch as much as ₦200,000 [$125],” Saddam said.

“Some hunters used to cut off the tusks before selling the carcass. Traders often did the same,” Saddam noted. “I know the hunters sold the tusks, but to whom and for what purpose—we never knew.”

Though smaller, warthog tusks are made of the same dentin as elephant ivory. When polished, they closely resemble it. Their growing demand quietly fuelled an illicit economy that had already adapted.

The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) highlights that poachers illegally hunt warthogs across Africa for their ivory tusks, which, unlike elephant tusks, are not illegal to sell, and for their bushmeat.

While international ivory trade was banned under the 1989 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), many countries still permitted domestic ivory trade, leaving gaps exploited by traffickers.

Warthog ivory proved easier to source. The animals reproduce quickly, are less protected by conservation laws, and can be hunted with far less risk. The tusks, sold discreetly, are often absorbed into larger smuggling operations moving westward.

“The meat is processed in Molai, in Baga Road, and in an area called Low-cost B, near Maimalari Barracks,” Saddam said. From there, it is packaged and transported to southern Nigeria. As for other parts—horns, bones, antlers—they are shipped to Kano, then to Dawaki Market in Jos, and finally to Lagos, where many are smuggled abroad, he added.

This shift illustrates not only the adaptability of illicit networks but also how deeply embedded they are in the region’s insecurity. In some instances, warthog ivory now supplements funding for insurgent groups—yet another commodity fuelling Nigeria’s conflict economy.

What begins as a story of animal trafficking unravels into something much bigger: a tale of how war, poverty, and organised crime collide to endanger biodiversity, destabilise local economies, and threaten livelihoods in one of Nigeria’s most fragile regions.

How warthog ivory fuels terrorism

The illicit trade in wildlife products has long been a source of funding for terrorist organisations across Africa.

A 2014 report by EnviroNews observed that illegal wildlife trade, including ivory poaching, was a significant funding source for Boko Haram. The report estimated that the illegal trade in wildlife products generated approximately $20 billion annually, with a portion of these funds used to support terrorist activities.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has expressed concern over Nigeria’s role in the trafficking of illicit wildlife. Despite efforts by the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA), Nigeria remains a significant transit point for ivory destined for Asian markets.

To tackle this, the government revised the Wildlife Conservation Act in 2016. “It’s now being enforced effectively by the NPS and NESREA,” Goni, the Nigerian NPS boss, said. He added that this is done with support from relevant government bodies like the Nigerian Customs, Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA), Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU), Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), and Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC).

Successes have been recorded in this regard. In January 2024, NESREA destroyed 2.5 tonnes of confiscated elephant ivory worth approximately $9.9 billion. The Nigerian authorities also recently, in April 2025, seized over three tonnes of pangolin scales.

However, the destruction of ivory stockpiles alone may not be sufficient to curb the illegal trade. The demand for ivory in international markets, particularly in Asia, continues to drive poaching and trafficking activities. As long as there is a lucrative market for ivory, insurgent groups and criminal networks will find ways to exploit wildlife resources to fund their operations.

The shift from elephant to warthog ivory illustrates the adaptability of illegal wildlife trade networks and their ability to find new sources of revenue. This adaptability poses a significant challenge to conservation efforts and highlights the need for comprehensive strategies that address both the supply and demand sides of the illegal ivory trade.

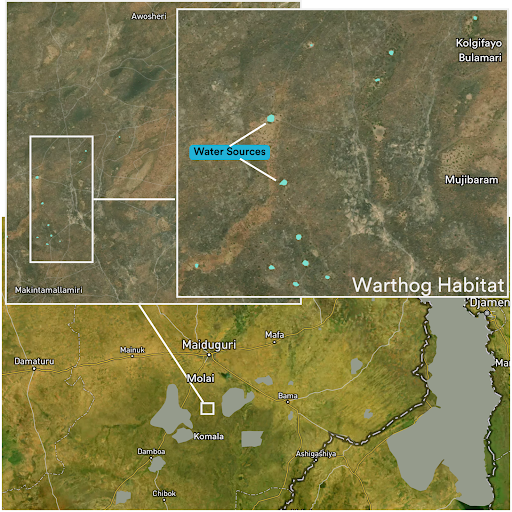

HumAngle’s investigation reveals massive exploitation of wildlife animals, especially warthogs, by terrorists operating in the Molai wilderness, a known unregulated forest zone. While parts of it fall within reach of a nearby military base, vast areas remain outside regular patrols. These areas are also riddled with abandoned settlements and water patches, coinciding with the migratory corridors of both elephants and warthogs around the Kayamala forest areas.

Heading southward, one encounters more wilderness areas bordering terror-controlled zones, including parts of Sambisa Forest, Komala Forest, and Erwa Nature Reserve near Damboa.

Groups like Boko Haram and ISWAP, active in Molai and Konduga, contribute both directly and indirectly to the warthog threats. Boko Haram attacks have displaced communities and left behind lawless zones where poaching thrives unchecked.

Terrorist activities — landmines, arson, and habitat destruction — further degrade the fragile ecosystems that warthogs and other wildlife rely on. Satellite imagery from 2020 shows extensive village burnings near Konduga, supporting reports of habitat destruction affecting warthog foraging grounds.

Peter Ayuba, Director of Forestry and Wildlife for Borno State, reported in 2022 that wildlife, including elephants, hyenas, and likely warthogs, stray from Cameroon’s Waza Game Reserve into Borno’s border regions like Konduga, where they are frequently hunted.

Warthogs, although smaller in range than elephants, show similar seasonal movement patterns. In the Sambisa-Molai-Konduga axis, they follow the Yedseram and Ngadda rivers, moving between Sambisa’s forests and the grasslands and farmland patches near Konduga and Molai.

Additionally, corridors like the Mandara Mountains/Gwoza Hills link Nigeria to Cameroon’s Waza National Park. Warthogs might use this route to access wetlands in the dry season and return to the Nigerian savannas in the rainy season, much like elephants.

The Chad Basin National Park–Waza National Park corridor also offers a secondary pathway for warthogs, aligning with Ayuba’s 2022 observations of wildlife incursions from Cameroon into northeastern Nigeria.

The human toll

The illicit warthog ivory trade—entwined with insurgency, criminal syndicates, and the erosion of rural life—has inflicted a profound and often invisible cost on communities across northeastern Nigeria. Beyond its environmental destruction, the human toll emerges in fractured livelihoods, forced collaboration with insurgent groups, and the gradual collapse of long-standing social and cultural systems.

In rural Borno, civilians have been forcibly co-opted into terrorist logistics chains. In Kawuri, Konduga LGA, Saddam explained that residents are compelled to act as middlemen, tasked with selling poached wildlife, including warthogs, in Maiduguri’s markets. Others are coerced into ferrying food supplies, medications, phone recharge cards, and other essentials to insurgent hideouts in forested areas like Sambisa.

These forms of forced labour are not isolated incidents. In April 2024, six individuals were arrested by Nigerian troops in Mafa LGA while transporting a truckload of Arabic gum worth ₦2 million ($1,236)—allegedly intended for sale to fund Boko Haram activities. Five months later, in September, the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) apprehended Garba Buda in Guzamala, a key logistics courier for Boko Haram, who was overseeing supply movements between Monguno and the Southern Tumbus.

Earlier, in March 2023, MNJTF troops captured three more suspected insurgent logistics suppliers in Borno. They were found with terrorist-issued access passes and invoices for items to procure—evidence of a highly organised supply chain supporting armed groups. In February 2022, local hunters in Mandaragirau village, Biu LGA, arrested six individuals suspected of ferrying food and arms into insurgent-occupied sectors of Sambisa Forest. The suspects later confessed. Most recently, in January 2025, Muhammad Idrissa, a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), was arrested for supplying cooking oil, seasoning cubes, salt, and pepper to Boko Haram on five separate occasions.

When security agents arrested three men in the Molai community with warthogs in a blood-stained bag, it was easy to fathom their alleged conspiracy and collusion with terrorists to trade wildlife animals. Insurgents have disrupted the traditional hunting systems, which were once central to local sustenance and cultural identity.

“Last year, the terrorists warned all hunters—anyone caught hunting warthogs would be killed,” said Lawan-Adamu. “They claimed the meat is haram, but the truth is, they wanted the animals for themselves. Not for religion—just profit. The hunters in Molai even clashed with them a few months ago because of this.”

The human consequences of this collapse stretch far beyond the poachers or the insurgents themselves. According to a joint report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and INTERPOL, profits from illegal wildlife trade rarely benefit local economies. Instead, revenues are funnelled into expanding arms networks, logistics infrastructure, and the operational reach of militant groups—fuelling the very insecurity that disempowers civilians in the first place.

In this environment of lawlessness, fear, and economic desperation, communities are being pulled further from self-reliance. Schools have emptied. Farmlands are abandoned. Market days have grown tense. Families are divided—some recruited, others displaced. What was once a rich, biodiverse landscape sustaining both people and wildlife has become a battlefield of survival, where silence often means safety.

The human toll of the warthog ivory trade is not abstract. It is a child dropping out of school to support a parent coerced into supply runs. It is the mother who scavenges for firewood while militants stalk the forest paths. It is the elderly man who can no longer hunt to feed his family, not because animals are gone, but because the forest is no longer his.

Inside the local wildlife market

In Maiduguri, hunted wildlife, such as warthogs, antelopes, hares, porcupines, and others, find their way to two local markets: Molai Market and Baga Road Market. There is a third, lesser-known point of sale — the traditional medicine market.

We visited the Molai Market and the traditional medicine market. The latter is tucked beside the Yola Distribution Company’s Bulabulin Business Unit along Maiduguri Road, just about 800 miles from the Monday Market. Upon entering, you are immediately enveloped by a dizzying mosaic of smells—earthy herbs, dried roots, and something else more pungent, more unsettling. Stalls brim with varieties of shrubs and dead animal parts. One shop in particular pulls you in. Here, a macabre collection is arranged in casual disorder: antelope horns and skulls, deer heads, reptile skins, fox skulls, bird wings and talons, feathers matted with dust. Inside, a caged porcupine paces restlessly. Just opposite, a crocodile’s hatchling lies trapped in another iron cage, watched over by the shopkeeper lounging on a stool. Near the entrance, pushcarts groan under the weight of bundled herbs and animal skins—antelope horns, crocodile hides, fox pelts—displayed to catch the eye of any curious customer or traditional healer passing by.

Molai Market, by contrast, feels more familiar, more alive in an ordinary way. It is a sprawling, local market along the Konduga-Maiduguri Road, where grains and livestock—donkeys, rams, cattle, goats—exchange hands under the open sky. But tucked into a more secluded corner, almost hidden from view, is another kind of trade. Here, among a knot of hunters and seasoned traders, wild animals are bought and sold. The market comes alive every Friday. Yet even on its busiest days, the traders wear suspicion like a second skin, wary of any face that does not blend easily into the crowd.

Warthogs’ limited range (1–10 km², sometimes up to 20 km²) means they cannot migrate far enough to escape targeted hunting. They are now facing an immediate threat of depletion.

Local sources told us that woodlands near Molai, Konduga, and around Alau Dam are hotspots for warthog hunting. Patches of water sources — small streams, ponds, and sections of the Ngadda River — provide critical habitat, but also make them predictable targets for hunters.

Satellite imagery places warthog habitats along the Ngadda River corridor—unfortunately, overlapping with abandoned, terror-controlled villages where insurgents are suspected or known to operate.

Between Molai and Konduga, the adjacent forest fringes of Sambisa position warthogs dangerously close to settlers who hunt them for food, trade, and black-market commerce, as confirmed by our interviews.

Those who spoke to us did so in hushed tones. They said antelopes, snakes, deer, and warthogs are among the most commonly traded animals. Warthogs, in particular, are not consumed locally; instead, they are grilled and transported southward to Nigeria’s coastal cities. Traders explained that a single warthog could fetch as much as ₦200,000 ($125), while its tusks alone could sell for up to ₦30,000 ($19). Carefully packed, the tusks and other body parts are sent to the southern states, where ports offer an easy gateway for exportation.

Among others, a former Boko Haram combatant, who asked not to be named over fear of reprisals, described the shadowy wildlife economy financing the activities of the terror group, especially those operating from the Sambisa Forest. He recalled, for instance, how the terrorists hunted down and traded elephants, forest pigs, tigers, crocodiles, snakes and squirrels in the local markets, working in cahoots with local hunters and slippery dealers helping them to transport the protected animals.

“They were transported by hunters to the market and sold to dealers who take them to the south to be eaten as bush meat, ” he said briefly, suggesting that, from the southern part of the country, he did not know some of the wildlife animals ended up in the global markets.

Profits, players, and global demand

At the heart of the warthog ivory trade lies an undeniable truth: it is a business, lucrative, shadowy, and fuelled by an insatiable demand that stretches far beyond Nigeria’s borders. While the poachers and low-level middlemen often operate under duress, the real profits are made higher up the chain by coordinators, exporters, and foreign buyers.

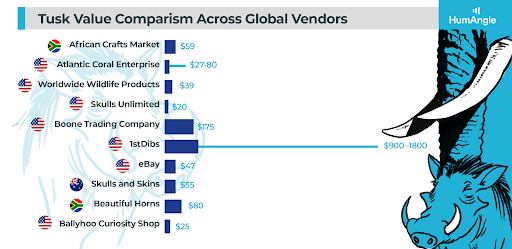

Though smaller than elephant ivory, polished warthog tusks, in bulk, can command significant value on illicit markets, sometimes fetching thousands of dollars depending on their finish and destination. Online retailers in the United States, such as Worldwide Wildlife Products, openly list warthog tusks measuring 7 to 10 inches for $15.99 to $39.99 each, depending on size and condition. Atlantic Coral Enterprise, another U.S.-based seller, offers large African warthog tusks (8 to 10 inches) at wholesale rates of up to $80 per pound. Ballyhoo Curiosity Shop, also a U.S.-based online seller, retails a warthog tusk for $25. These platforms form part of a loosely regulated online marketplace where warthog ivory changes hands with little scrutiny.

Across the continent, similar commerce flourishes. South Africa’s African Crafts Market lists warthog tusks between five and seven inches for as little as $10 a piece. Many of these tusks are scrimshawed—carved with intricate scenes of African wildlife—and marketed as collectables. The price increases with the complexity of the carvings and the size of the tusks, catering to tourists and collectors alike.

As the tusks ascend the value chain, so too do the profits—and the sophistication of the actors involved. Mid-level traffickers in Africa often pose as art dealers or curio traders, liaising with international buyers via encrypted platforms and private online forums.

The buyers range from high-net-worth collectors and black-market traders to traditional medicine practitioners, particularly in East and Southeast Asia.

This global demand fuels local supply. And as long as poverty, conflict, and lax enforcement persist, actors along the trade chain—from insurgent territories in Sambisa to auction rooms in Guangzhou—will continue to profit from this hidden economy.

Why warthog ivory remains unregulated

Unlike elephant ivory, which is subject to intense scrutiny and regulation, warthog ivory operates in a legal grey area that traffickers have eagerly exploited. This loophole has become a weak point in conservation policies across Africa and beyond, allowing poachers, middlemen, and international syndicates to operate with minimal fear of reprisal.

At the core of this oversight is the absence of explicit international regulation under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). While elephant ivory has been heavily restricted since 1989, banned from international commercial trade and listed under Appendices I or II, Phacochoerus africanus, the common warthog, is not listed in a way that limits the trade of its tusks. As a result, unless individual countries proactively legislate against it, warthog ivory remains legal under international law. And most have not.

Nigeria, for example, does not classify the warthog as endangered or protected under its Endangered Species (Control of International Trade and Traffic) Act of 1985, which largely mirrors CITES listings. In the absence of specific protections, the hunting, possession, and trade of warthog ivory remain unregulated. The result is an open channel through which ivory flows—mislabeled, underreported, and rarely challenged.

Traffickers have taken advantage. Reports from TRAFFIC, the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC), and the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) reveal how traffickers exploit this regulatory blind spot.

Within Nigeria, enforcement is hindered by fragmented wildlife laws across states. Outdated regulations—some inherited from colonial rule—have failed to keep up with the sophistication of modern trafficking networks. Rangers in forest and game reserves lack training to identify warthog ivory, and enforcement resources are thin. Even in Borno State, where the connection between poaching and insurgency is well-documented, no legislation directly addresses non-elephant ivory. The NPS and NESREA have launched awareness campaigns and livelihood support schemes in communities bordering protected areas, but officials acknowledge the scale of the challenge.

“We make sure that we go down to the grassroots and provide communities surrounding the national parks with alternative livelihood options. We train some of them with skills, and provide some with starter packs,” said NPS Conservator-General Ibrahim Goni. Yet he admits the constraints: “Managing wildlife is a herculean task… We also have to manage the human population. And we might not be able to meet the needs of every community.”

Meanwhile, warthog populations across northeastern Nigeria are declining. Hunters interviewed during this investigation reported dwindling sightings in the past five years—evidence that unregulated hunting is taking a toll on a species once considered resilient.

The ecological cost of unchecked poaching

The warthog might not evoke the same urgency as the elephant or the rhino in global conservation conversations, but its disappearance is a warning bell.

Warthogs, often dismissed as lesser species in conservation hierarchies, play a surprisingly important role in the savannah and woodland ecosystems they inhabit. As foragers and grazers, they help aerate soil through digging, disperse seeds, and provide prey for larger carnivores such as lions, hyenas, and leopards—predators that once roamed Nigeria’s wildlands far more freely.

With warthog numbers plummeting in regions like Borno—an area already reeling from climate change and deforestation—there is a growing imbalance in the food web. Apex predators, when they remain, are increasingly deprived of natural prey, pushing them to scavenge or venture closer to human settlements, increasing the risk of human-wildlife conflict. Meanwhile, the absence of seed dispersers like warthogs can alter the composition of vegetation over time, leading to further habitat degradation.

The methods used to hunt warthogs are neither selective nor sustainable. Poachers often use traps, snares, and firearms indiscriminately, leading to the death of non-target species such as antelopes, monkeys, and even endangered birds. During interviews conducted for this investigation, several hunters admitted that in the absence of warthogs, they resort to hunting “whatever moves,” including large snakes and porcupines.

The loss of biodiversity is not just a scientific concern—it also undermines ecosystem services that rural communities depend on. Pollination, natural pest control, water regulation, and even cultural practices tied to local fauna are being eroded with every animal lost to poaching.

Unchecked hunting also has cascading effects on vegetation and soil health. Animals like warthogs, bush pigs, and baboons disturb the soil in ways that encourage germination and nutrient cycling. Their removal slows down natural regeneration in post-burn areas or drought-stricken lands, delaying the recovery of tree and shrub cover essential for both wildlife and human livelihoods.

In forest corridors like Komala and Masafanari, which once served as thriving wildlife routes connecting Nigeria to northern Cameroon, local herders and farmers now speak of landscapes that are increasingly barren and quiet.

Northeastern Nigeria is already one of the regions most vulnerable to climate shocks in West Africa. Desertification, irregular rainfall, and rising temperatures are compounding the effects of conflict and displacement. Healthy wildlife populations help buffer these impacts by maintaining vegetation cover and supporting ecosystem resilience. Their disappearance accelerates land degradation, reduces carbon sequestration potential, and makes local communities more vulnerable to floods, erosion, and heat waves.

Wildlife is a living thread in the cultural fabric of many indigenous communities in Nigeria’s northeast. Local songs, proverbs, rituals, and storytelling traditions have long featured animals like the warthog, giraffe, or kudu as symbols of resilience, cunning, and communal identity. The disappearance of these animals marks not only an ecological void but a cultural erosion that affects intergenerational knowledge and local identity.

*Saddam Mustapha is a pseudonym used to protect the officer’s identity.

GIS analysis provided by Mansir Muhammed.

This story was supported by Code for Africa and funded by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

In northeast Nigeria, poachers and terrorist groups like Boko Haram have shifted from hunting elephants, which have migrated due to conflict, to targeting warthogs for their valuable tusks.

The warthog ivory trade has emerged as a lucrative black market that finances terrorism, contributing to regional instability. This trade leverages existing networks previously used for elephant ivory, and warthog tusks, though less regulated, are often smuggled and sold under the guise of legal commerce.

The ecological impact of this unregulated poaching is significant, leading to biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. Warthogs, key players in their ecosystems, are declining rapidly, which disrupts food webs and exacerbates human-wildlife conflicts. This decline is joined by a human toll, where impoverished communities are coerced into supporting insurgents, reducing local self-reliance and cultural integrity.

Despite efforts to curb illegal ivory trade, existing loopholes and market demands continue to challenge conservation and security efforts.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter