Farmers and Fishers in Nigeria’s North Caught between State and Non-state Attacks

Civilians, particularly farmers and fishermen, are often caught in the middle of terrorist activities and counterterrorism operations in the northeast and northwest regions of Nigeria. This combines with the impacts of climate change and leaves their livelihoods interrupted and their food supply affected.

The call connected after a few rings, and his voice emerged, low and steady over the soft hum of mourners from the background. They were praying for the souls of those lost.

“The military mistook my colleagues for terrorists,” Abdulsalam Abubakar began. “We often spend seven to 14 days on the shores of the water whenever we go fishing.”.

The 30-year-old and his fellow fishermen often fished on the shores of Lake Chad, rowing canoes to navigate the stretches of the water. That fateful week in October, they had travelled to Tilma, an island village a few kilometres from their community in Baga, Nigeria’s north-east, to fish with their pass tickets from the military – a temporary permit, allowing them a maximum of 14-day fishing window. However, as the days drew to a close, a tragedy struck. An airstrike was launched on the shores on the last Wednesday of the month. Reports indicated that the Chadian military, retaliating after a terrorist attack on their base that had claimed 40 soldiers, mistook the fishermen for Boko Haram terrorists in the chaos that followed.

Abdulsalam described the days preceding the fatal strike, recounting that “the terrorists had attacked the Chadian base and killed their fighters. Afterwards, they went in different directions—Niger, Cameroon, and towards Tilma, the village where we were fishing here in Nigeria.”

“It was said that the Chadian military then called for air support from Nigeria. So when the military was surveilling the area, they mistook fishermen for terrorists,” he recounted. Abdulsalam escaped the incident only because he had left the shore a day earlier to attend to an emergency.

Nigeria and Chad are part of a regional security coalition, the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), dedicated to combating the Boko Haram insurgency. Other member countries include Niger and Cameroon.

“The fighter jet kept surveilling the area from morning until the next day. It launched at anything moving, even at flashes from torches at night. Two more jets came the following day. Five of my friends died in the airstrike. Five more colleagues sustained varying degrees of injuries,” Abdulsalam recalled.

Among those he lost were three he held close: Ahmadu, Ayuba, and Abubakar—two nephews and a brother-in-law. Abdulsalam’s voice faltered when he spoke of them.

“I was closer to Ahmadu,” he said. “He spent his teen days in our ancestral community, Raha [a village in Bunga LGA of Kebbi State, northwest Nigeria], before relocating to Baga in 2004. Although he was 40, much older than me, he was my friend.” He described him as hardworking, always looking out for his family. “He looked after his younger siblings, too,” he added, his voice breaking slightly. “His death really shook me.” His silence carried more than his words for a moment until he continued, grounding his grief in faith: “But it was Allah’s will. We cannot question His decision. His family is also greatly affected. It has only been a week, but his absence is felt deeply.”

Idris Usman*, one of the deceased’s (Abubakar) brothers, recounts his reaction the morning he learned of his brother’s death.

“I was seated in front of the house when the news of his death reached me,” he said. “It was around 6:30 a.m. A man rode up on a bicycle and parked beside me. After we exchanged greetings, he told me that the fighter jet from yesterday had caused a lot of damage,” he paused again, sighing heavily. “Then he added that our people were part of this damage. I panicked and quickly asked, ‘How is my Habu? Is he safe?’ And he told me, ‘I received his news, too. I am sorry. He died, too.’”

A legacy of violence: civilian casualties and unresolved conflicts

The Nigerian military in Baga treated those wounded at their base’s clinic. “They also tendered apologies to the families of those who died,” Idris told HumAngle. “The Brigade Commander had earlier issued a warning to be passed to the families of fishermen who were on the shores to ask them to return home because the terrorists had attacked the Chadian military’s base, and they were preparing for retaliation. We did not get the message on time until the following day, the day the military operation happened.”

However, this is not the first time civilians, particularly farmers and fishermen, are risking violent interruption of their livelihoods in the region. They are often caught in the crossfire. “The military often mistakes us for terrorists. And sometimes, they suspect us of aiding them. We were not spared by the terrorists either. They also accuse us of disclosing their locations to the military. We are always victims of suspicion,” Abdulsalam revealed.

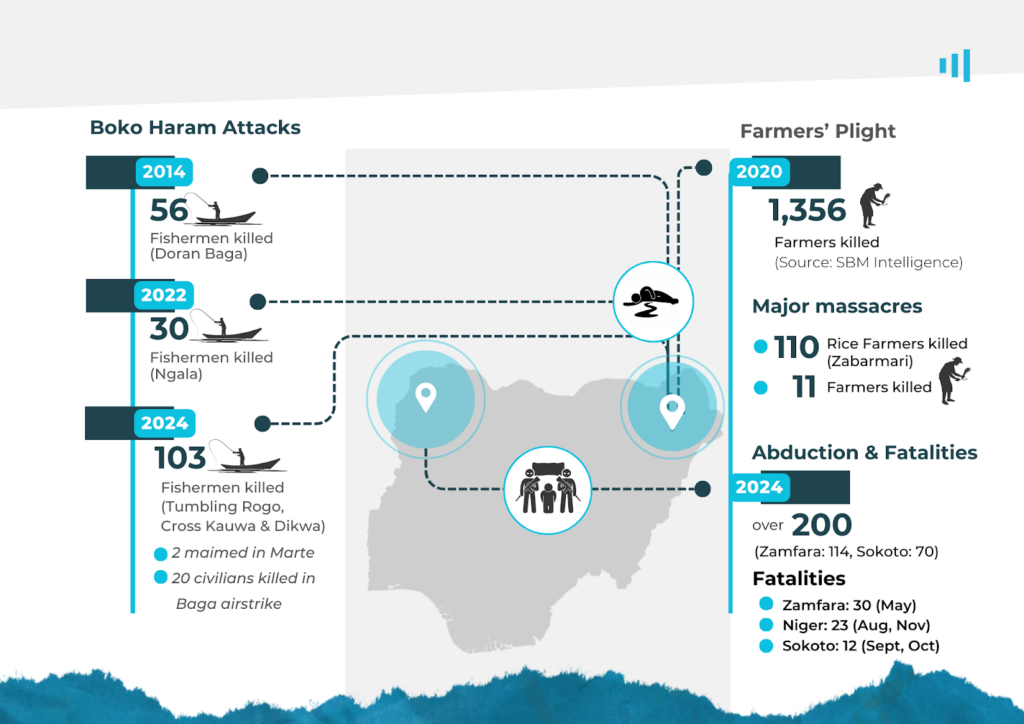

In 2014, Boko Haram terrorists killed 56 fishermen in Doron Baga. In 2022, they killed 30 fishermen in Ngala, and this year alone, 103 have lost their lives to violence in the region. Specifically, 31 lost their lives in Tumbun Rogo, 15 in Cross Kauwa, and 37 in Dikwa. Two also had their hands cut by the group in Marte. The group also forces them to pay levies before they can access water. Most recently, 20 people were killed by Nigerian military airstrikes in Baga this August. Families often struggle to retrieve and bury the dead, like in the recent Baga incident, where access to the area remains unsafe. “It is unsafe. This is the seventh day since he died,” Idris stated.

Farmers have suffered similar attacks. In November 2020, 110 rice farmers were gruesomely massacred by terrorists in the Zabarmari area of Jere, followed by 11 more in November 2023.

The interruption extends to the northwest, where terrorists have abducted over 200 this year alone. In Zamfara, 105 were kidnapped in May, nine more in October, and another 70 in Sokoto in June. The violence in the region also claimed the lives of some. In May, 30 were killed in Zamfara, while 13 and 10 were killed in Niger in August and November respectively. In Sokoto, eight were killed in September and another four in October. Ongoing farmers-herders clashes further complicate these attacks. According to SBM Intelligence, a Lagos-based consultancy, 1,356 farmers have been killed in Nigeria since 2020.

Food insecurity: the compounding impact

The obvious implication is food insecurity. It is notably harsher on vulnerable communities as these impacts combine with climate-induced impacts like drought and flood. Families–particularly widows–of victims of these attacks often find it difficult to fend for themselves with the death of their providers. When Idris’s eldest brother died, Abubakar took over the responsibility of fending for his siblings, his family, and his late brother’s family. Now Abubakar is gone, too, leaving behind six children. Idris, only 26, now faces supporting them.

“I am overwhelmed,” he said. “The responsibility of taking care of them, our aged mother, and my younger siblings is now on me,”

He is more frustrated as his farm has been affected by the impacts of climate change. “Most of my crops died due to drought and insects. I had planted six big measures of beans, expecting to harvest at least five bags. However, I barely got ten small measures. My rice farm also got flooded,” he revealed.

“Food items here are also expensive. We used to rely on our harvested crops. However, this season, they were washed away by flood. Traders would often travel to Maiduguri and other places to bring the food items we buy. The roads are safe. A small bowl of local rice is sold at ₦5000 [$2.98]. Slightly affordable maize is sold at ₦2500 [$1.49]. And one packet of pasta is ₦1100 [$0.66]. So, we are pleading with the authorities to help us with food aids and farming tools,” Abdulsalam added.

HumAngle has previously reported how the food supply in Borno was affected by constant attacks on farmers abandoning their fields for their safety, wasting millions of crop investments. A recent report also shows how this continues to affect vulnerable communities, causing food insecurity and malnutrition, especially among children. A 2014 report by the World Bank indicates that this is not a recent issue. The international development organisation showed that food insecurity is a major concern in the north-east, north-central, and south-south regions, with the north-east being the most affected.

A recent analysis by the Global Network Against Food Crises indicates that Food insecurity in Nigeria will likely remain high due to heightened insecurity and conflict in northern zones, weakening macroeconomic conditions with 33 per cent inflation year-over-year, higher costs and lower agricultural production. Similarly, according to an analysis led by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and the United Nations World Food Programme, 33.1 million Nigerians are projected to face food insecurity in 2025. Economic hardship, record-high inflation, climate change impacts and persistent violence in the northeastern states drove the projection.

Children are the most hit. A recent survey by the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, National Population Commission, and a World Health Organisation framework, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), shows that children’s nutrition health in Nigeria has suffered considerably over the last six years, making four out of every ten children under five years stunt. An analysis by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) also reveals that One in eight children was significantly impacted by the ten biggest extreme weather events this year.

“We pray for God to support the military,” Idris said. “We are pleading with the military to take the territories controlled by the terrorists. The government should provide them with the necessary resources to fully take care of these terrorists,” Abdulsalam added.

“We hope this insecurity becomes a thing of the past soon,” Idris said quietly.

“We would appreciate it if they would be careful to investigate and differentiate between fishermen and terrorists before carrying out any operation. Fishing is the only source of income for most of us in Baga. And these waters are places we could fish. And we keep getting killed in these circumstances,” Abdulsalam said.

Editor’s Note: Asterisked names are pseudonyms used to safeguard the sources’ identities.

Abdulsalam Abubakar recounts a tragic incident in Baga, Nigeria, where he and fellow fishermen, mistaken for Boko Haram terrorists, were attacked by the Chadian military, leading to several casualties.

The fishermen often faced similar risks due to regional conflicts, and Abdulsalam narrowly escaped the strike.

Civilians, particularly fishermen and farmers in Nigeria's northeast, regularly face violent disruptions, being caught between military operations and terrorist attacks.

These events have led to food insecurity, exacerbated by climate change impacts like drought and floods. Vulnerable communities, already struggling with high commodity prices, seek aid and intervention.

The consistent violence underscores the need for coordinated efforts to protect civilians and ensure food security.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter