Families Of Fallen Zamfara Community Guards Remain Haunted By Loss

The state authorities asked able-bodied men to take charge of security in their communities but had no plan for their families, who now live in untold hardship after their loved ones were killed by terrorists.

Residents scampered for their lives when terrorists invaded the Tsafe area of Zamfara on the evening of March 24, 2024. But Aminu Muhammed stood his ground with other men of a government-backed militia to repel the attack.

The bustling town of Tsafe in North West Nigeria had grown quiet, except for the heavy metal-clanging roar of the military vehicle patrolling the streets. Many locals had somehow retired for the day, too. It was unusual. But there had been some tension in the air since the raging conflict found its way to the town nearly a decade ago, especially that week in March.

Shortly before the fateful day, the motorcycle-riding armed gangs raided the town, killed a ward head, and abducted three people. As if that wasn’t enough, two days later, they stormed the town and took another five people away.

That Sunday evening, it was not long into the night before their fear came true. Residents started hearing gunshots from the eastern part of the town, where the military engaged the terrorists until they split and found their way to the northern part. Aminu and his men were ready to hold the fort for the military to join them, but they were soon overpowered. The security outfit, known locally as the Askarawa, was only licensed to carry pump action rifles against the AK47-wielding terrorists.

That last line of defence Aminu led as the sector commander of the outfit in the town cost him his life. He was shot multiple times in the chest. The terrorists also burnt two operational vehicles belonging to the Army and the guards before retreating into the forest with six civilians.

In her dimly lit room, Aisha Muhammed, his wife, patiently awaited his return. She had prepared his favourite meal, and the aroma still wafted through the air. She had also ensured that his gadgets, including the headlight he would need for his regular routine, were fully charged before he went out. Yet, as the night wore on, sleep eluded her. At first, Aisha’s eyes darted across the room, but they would soon remain fixed on the door, her mind racing with fresh worries as the silence of the night grew deeper.

Later, she drifted off, but Ismail, her eldest son, came knocking to ask what was happening in the house. “Nothing was happening,” she replied. “I then said that since NEPA [the local parlance for the electricity provider in Nigeria] brought light, Abba Hurairah [her husband] went out, but wherever he is, I’m sure he’s on his way. As you can see, it’s time for the dawn prayer.”

Instinctively, Aisha sensed something was amiss but couldn’t quite grasp what it was. She tried to dismiss the feeling and attributed it to hunger. “I went to the kitchen to get some leftover tuwo,” she recalled. “I didn’t know what was going on. I never even considered he might be dead. If anything had happened, I thought, he would probably suffer a gunshot wound and be in the hospital. There were times it happened like that.” As she sat down with the food, her appetite suddenly vanished, she told HumAngle. The tuwo, usually a comfort, now sat heavily before her.

“I was about to start eating when Yaya came in crying and saying that Baba had been killed,” she said, teary-eyed.

Aminu had escaped death by sheer luck many times before. It was a ritual she knew so well. He would delightedly narrate his exploits and end it every time with a triumphant grin. He had told her about Ibrahim, one of his boys, who was hit because the bullets narrowly missed his own throat by a hair’s breadth. She remembered the heated exchange of gunfire he told her about when they responded to a distress call along the Tsafe-Funtua highway and rescued a couple.

Since 2011, Zamfara has been the heartbeat of the conflict ravaging North West Nigeria. Terrorists, locally known as bandits, have become increasingly deadly as they spread their campaign of terror. There are believed to be as many as 30,000 of them, operating in more than 100 gangs in the region, raiding villages, sexually assaulting women, and imposing levies on communities. They have killed over 20,000 people and run a million-dollar kidnap-for-ransom enterprise to fund their operations.

Authorities have clamped down and launched offensives into their hideouts. They had also dialogued and offered them amnesty in the past with a view to disarm them. But when that failed, state forces started conducting air raids into their camps in the forest and designated them as terrorists to allow for stiffer sanctions. Still, thousands of the terrorists continue to occupy large swathes of the region’s ungoverned spaces, which they use as springboards to launch their attacks or hideouts to stockpile weapons and hold their abductees.

A child of necessity

Security response is often slow or absent in rural areas because state forces are stretched thin due to conflict elsewhere in the country and are unable to adequately deal with the situation in the region. So, as the conflict spread, authorities mulled the idea of creating a security outfit to fill the gap.

In January this year, the Zamfara state government inaugurated at least 2,645 Community Protection Guards (CPGs) and charged them with restoring peace in the troubled state, promising to provide them with all the necessary support to discharge their duties.

Barely eight weeks into their operation, the commandant of the guards, Colonel Rabiu Garba, was suspended. Although no reason was given, local researchers say it was not unconnected to a press interview he granted in which he accused the state government of poorly funding the group. “Lack of funds and other logistics are responsible for our non-performance… You trained somebody, gave him a gun to fight criminals, then you refuse to pay him his monthly allowance, and you cannot fuel his vehicle. How do you expect him to perform?” Garba had lamented.

HumAngle gathered that they were later paid their outstanding allowance after the interview. Multiple interviews conducted with families of deceased guards, however, revealed that there are not yet any formal death benefits for guard members who died while on active duty. This is in spite of the fact that the state established a security trust fund to help with a sustainable funding mechanism to tackle the conflict.

Analysis of media reports shows that at least nine members of the state security outfit have been killed across the state this year. Local analysts blame the situation on the poor training given to the guards.

“Members of the guards were not provided with adequate training before they were hurriedly recruited and inaugurated. So, it poses a risk as to how they conduct themselves around terrorists. They need training to know how to engage and when to disengage while fighting bandits,” a researcher with a deep understanding of the guards’ operations told HumAngle.

The state government only recently promised to look into the welfare of families of CPG members who have lost their lives nearly seven months into their operations. HumAngle reached out to authorities in Zamfara to provide specifics of the plan. As of the time of filing the report, multiple texts and calls made to the spokesperson for the governor, Sulaiman Idris, were not returned.

An endless nightmare

“When he was alive, we were honestly living a life similar to that of birds. If we found enough for today, it would suffice until tomorrow,” Aisha’s eyes were distant as she recalled those times. Since her husband’s death, the family of 14 has been subsisting on the kind gestures of individuals and community leaders. The once-bustling household filled with the laughter of children now feels eerily quiet.

“We have lost more than a provider,” Aisha whispered, her voice breaking at a regular pace. “His life meant more to us than anything we could get now. But after his death, the governor sent us maize and rice. Aliyu MC [a community leader] gave us ₦100,000 and a bag of rice. The Emir did the same,” she recalled. As we spoke, one of her younger children tugged at the edge of her wrapper, a silent reminder of the many mouths she still has to feed.

Hauwa Umar didn’t enjoy much of such goodwill when her husband, Umar Faruk, was killed. “During his burial, some soldiers came to visit us, and that’s all we’ve gotten so far,” she said.

One Monday morning in June this year, Farouk and one of his sons were out on their farm, the early morning breeze brimming with promise, when terrorists besieged his farm. Faruk knew the nature of his job as a member of the protection guard would constantly put a target on his back, but it never occurred to him that it would be at his most vulnerable moment.

Sensing the situation, he pushed his son towards safety as the terrorists closed in on him. He reached for the old Dane gun he always carried and fired at the gangs. They returned the gunfire. One whistled past him, and another hit him in the arm. “He kept on running with a bleeding arm, shouting for help. They finally caught up with him at the entrance of the town and shot him severally,” she told HumAngle. Faruk fell to the bullet wound. “Before he left, we joked and laughed heartily. Unknown to us, that would be our last moment together.”

Hauwa sat on the threadbare mattress in one corner of the damp room, observing her mourning period in Gusau, the state capital. A bowl with sand-filled rice she plans to cook later in the day lies beside her. The pain of losing her husband has not eased one bit, and life has become a constant struggle for the mother of seven.

“Life is difficult, honestly. It is not easy for those whose husbands are alive, let alone for someone whose husband is dead.”

Living in constant fear

Since her husband’s death months ago, Aisha has been living in constant fear, stretching her neck at every creak or footstep in their room-and-parlour apartment. The house, nestled within a large compound, no longer felt like the sanctuary it used to be for her. While Aisha was in the restroom one Friday, her worst fear knocked on the door. Her room was burgled, and some valuables were gone, including their only TV.

“Since losing him within this household, we have all been in a state of fear even though it is God that protects. People keep breaking and carting off with anything they lay their hands on. There are times I would hear footsteps approaching, too, but with no one in sight. If Baba were alive, they wouldn’t have had the guts to break in. He was the only one who could look around and protect us,” she said.

The nature of the job pits the guards against many odds. One from the terrorists who understandably single them out as they did to Faruk for taking part in offensives against them. Also, the Zamfara-based researcher observed that some community members feel they are one of the reasons the crisis has festered. So, they “could as well target the family members. The extra-judicial killing and irresponsible style of interrogating suspects make the CPG guards and their families a target of strained relationships and even attacks”.

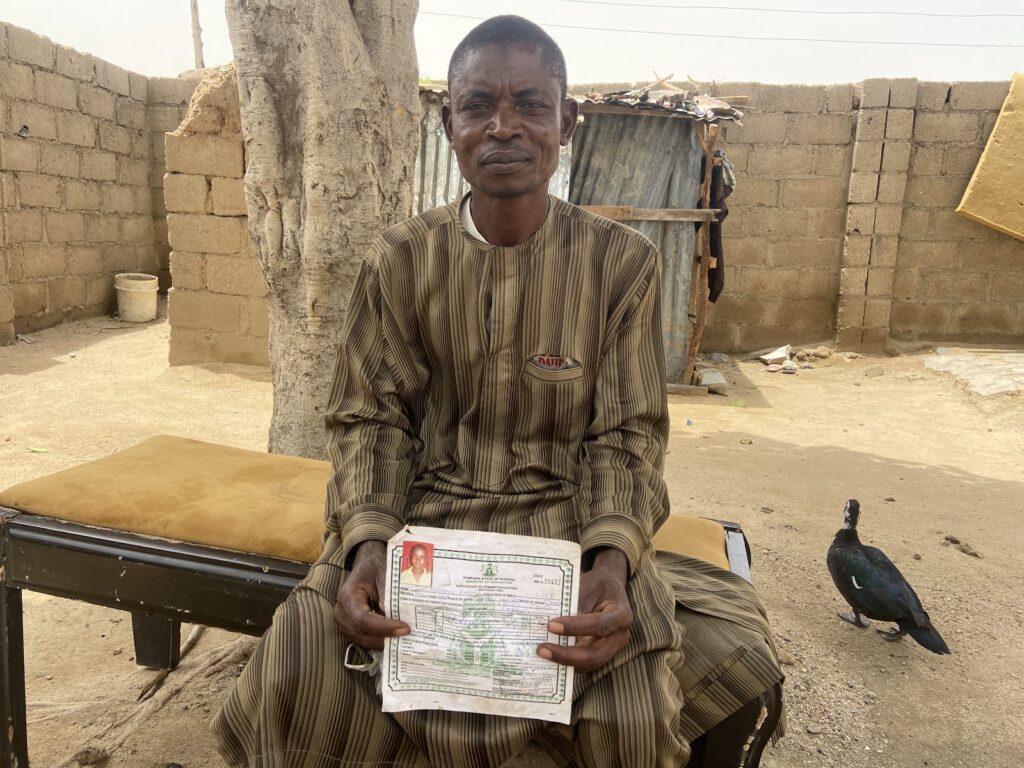

Those were exactly Ibrahim Kabiru’s concerns before he was killed during one of the terror attacks in Tsafe. Ibrahim, 17, would barely sleep in the same room with his family because he feared the terrorists might hound him down. “He used to tell us how dangerous the task was. I still insisted that he come home to sleep once in a while, but he would say he didn’t want to put us in danger and that he was scared the terrorists would follow him home. That’s how I didn’t get to spend much time with him,” his father, Ahmad Kabiru, 57, recalled.

The family sells vegetables at the popular Tsafe market. A day before Ibrahim lost his life, Kabiru had given him a bag of lettuce to sell. He was always eager to help. And by evening, Ibrahim returned with a smile, handing the father of four all the money from the sales.

Later in the evening, the boy joined the family for dinner before stepping out for his night shift.

“I watched as he brought out his cooler, carefully mixing yoghurt and fura together. He was about to leave when I asked him to please come to the market in the morning. Till tomorrow, if I ask the kids to do something and they refuse, Ibrahim will always come to my mind.”

After his burial, the uncompleted apartment building where the family lives played host to sympathisers who had come to commiserate with them.

“Ibrahim was courageous and stood firmly while protecting the people. And then Ali [a family friend] brought a man called Mazawaje [a lawmaker representing the town in the State House of Assembly]. He gave us five bags of corn, five bags of rice, and ₦300,000 as a gesture of support.”

Later in the day, the emir also visited and handed the family the sum of ₦50,000.

Kabiru said he used some of the money to build a fence around the house. It was one way he could feel safe from prying eyes. Also, Ibrahim, who was always concerned about their safety, would have approved of it.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter