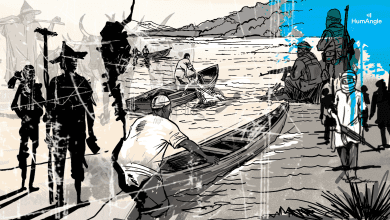

Examining The Europeanisation Of Security In The Sahel

The German Parliament on Thursday, May 14, debated an extension for the German Bundeswehr (Armed Forces) deployment in Western Africa Sahel region to support Anti-Terror and security missions.

The Federal Cabinet had proposed an extension of Bundeswehr participation in the European Union’s training mission and the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

Germany’s deployment is part of a wider European and French intervention in the volatile Sahel ravaged by violence perpetrated by militias, Islamic State- affiliated Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin.

EU member States complement French operation Bakhane that evolved and expanded from the French military campaign in 2013, called ‘’Opération Serval’’, against Jihadi groups and militants in Northern Mali.

Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Mali, The Netherlands, Niger, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the UK recently pledged to participate in the new counter-terrorism special operations Task Force, ‘’Takuba’’, in Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali.

According to the United Nations, attacks in the tree countries killed at least 4,000 people in 2019.

In April, the European Commission announced an additional 194 million euros to help strengthen the security capabilities and development efforts needed for security, stability and resilience in the Sahel. The EU website says the commission mobilised 4.5 billion euros between 2014 and 2020 for military operations in the region.

While European intervention in the Sahel appears to be about bringing stability, combating terrorism and strengthen the G-5 Sahel joint force that comprises troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, they are also about Europe’s security and efforts to stop the flow of migrants into their territories.

France, the EU and even northern European countries such as the UK see the restoration of stability in the Sahel as important for their own security as well as that of the region, Paul Melly from the African programme at Chatham House said.

They recognise that the current security crisis in the Sahel is a threat to the stability and prosperity of West Africa as a whole; that is why they are committing troops and money to the campaign against jihadist groups in the central Sahel and in the Lake Chad Basin, Melly explained.

West Africa is a near neighbour to Europe linked by close human and economic ties and shared interests in tackling issues such as climate change. Crisis in West Africa inevitably makes itself felt in Europe, in economic and social terms, and not just politically “hot” issues like informal migration.

So, fundamentally, that is why the EU and individual European countries have provided sustained support for economic recovery and development in the region while business opportunities in mining, oil or other sectors, are interesting for Europe, he said.

Melly also said Europe, broadly believed that the stability and development of this close neighbour was not just right, “a good thing” in moral terms, but also in its own self-interest.

Tackling the current security crisis in the Sahel is vital and explains why not only France, the traditional partner, but a host of other European countries are committing troops and money to the campaign to stabilise the Sahel, he added.

“I think the increased presence of western armies in the Sahel comes with a lot of mixed reactions and many people regard them as existing in the Sahel to promote other things other than security. There have been demonstrations by civilians in Mali against foreign troops,” Abdul Rauf Zanya, a Human security analyst from Ghana, said.

“Despite the presence of foreign troops and the excellent intelligence they possess, attacks still continue and people die almost every time,” Zanya said.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs May 2020 report states that “6.9 million people in the Sahel are grappling with the dire consequences of forced displacement. Almost 4.5 million people are internally displaced or refugees – one million more than in 2018 – and 2.5 million returnees are struggling to rebuild their lives.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter