Drought, Conflict Heighten Malnutrition Risks In Niger Republic, Northwest Nigeria

Climate vulnerability and conflict continue to exacerbate the nutrition crisis in Niger and Nigeria.

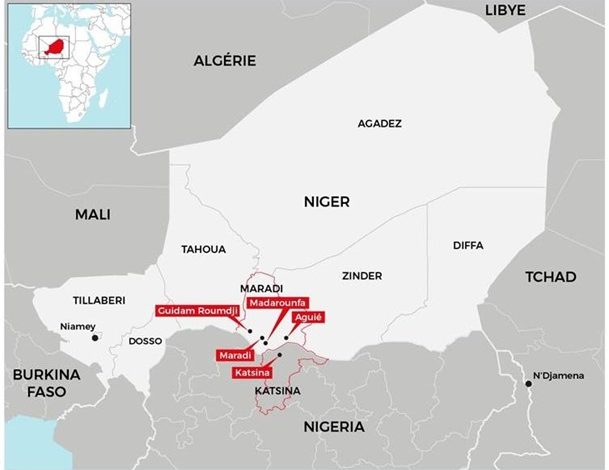

Extreme drought, poor harvests, and displacement are causing starvation and malnutrition that threaten children’s survival in the Maradi, South-central Niger Republic and Katsina State, Northwest Nigeria.

Hunger is at its extreme level in Niger where an estimated 14.7 million people in a 25.1 million population mainly live on arable land as climate vulnerability worsens food insecurity in the country. According to government reports, harvests across the country are 39 per cent down on the previous five-year average. The deficit is principally due to the drought in 2021, which, according to the United Nations climate agency, is comparable to the ones in 2004 and 2011. The drought conditions have aggravated a nutritional crisis exponentially. The situation is even direr in Maradi region where conflict has eroded people’s means of livelihood – mostly, farming.

The conflict is an overlapping extremist threat from the Lake Chad region which it borders. Continuous influx of refugees from Nigeria, Mali and Burkina Faso has strained the region’s limited resources, causing fighting within the location. Robberies, kidnappings, and other physical abuses are also frequent in Madarounfa district. For instance, on Feb. 18, 2022 an airstrike by the Nigerian Air Force hit Nachambé village, near the border with Nigeria, killing at least four children; this marks a sign of escalation in the violence in the region.

This has forced people out of their homes and farmlands. The farmlands have, in turn, remained unused and prone to desert encroachment, leading to food shortages.

Malnutrition is becoming endemic in Maradi because people lack access to nutritious food since poverty spreads as the influx of refugees keeps growing.

In 2021, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) treated 30,000 hospitalised children, – over 12,000 of them suffering severe acute malnutrition and medical complications. The medical charity provided another 35,000 severely malnourished children with outpatient care. But in 2022, the situation is expected to worsen.

“Several indicators now suggest the situation will be even more critical during the annual hunger gap that usually begins in about June,” Scheherazade Bouabid, MSF’s Regional Communications Manager, said in a March interview.

According to IPC forecasts (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification), by June 2022 as many as 3.6 million people in Niger could be in a situation of food crisis (IPC phase 3 or above), that is, 15 per cent of the population, and nearly 1.3 million children suffering from acute malnutrition.

Katsina’s worsening situation

The situation is not any better in Northwest Nigeria’s Katsina State which borders the Maradi region.

Gored by insecurity, Katsina is facing a large-scale displacement crisis caused by the non-state armed groups. As people move into the neighbouring Maradi region, conditions in resettlement camps are abysmal. Some live in Katsina in the day with barely enough food to sustain after losing their farms to insecurity, and sleep in Maradi in the night. The condition predisposes many children to poor nutrition. Again, poverty increases the chances of malnutrition, and the impact of COVID-19 worsens the situation.

The prevalence of malnutrition in the state permeates the pre-COVID-19 era.

According to the Nigerian Health Demographic Survey of 2018, Katsina is above the national average of malnutrition. The proportion of stunted children stood at 61 per cent, coming third position of highest prevalence in Nigeria.

The situation is also worsened by the lack of access to quality healthcare, with rising insecurity in the region. An estimated 3.3 million people in the Northwest lack access to safe water, and as a result, vulnerable children are becoming acutely malnourished after repeated bouts of diarrhea disease.

Funding Shortfalls

As Niger and Nigeria brace up for a food emergency following severe drought and a COVID-19 induced surge in food prices, humanitarian actors are concerned that funding allocated to the prevention and treatment of acute malnutrition has plummeted in recent years.

The situation will get complicated with the Russia-Ukraine war as donor agencies are diverting funding to support the humanitarian conditions in Ukraine, aid actors have said.

“We fear that by redirecting humanitarian budgets to the Ukrainian crisis, we risk dangerously aggravating one crisis to respond to another,” Mamadou Diop, Regional Representative of Action Against Hunger, said, adding that the humanitarian crisis in West Africa is the least funded.

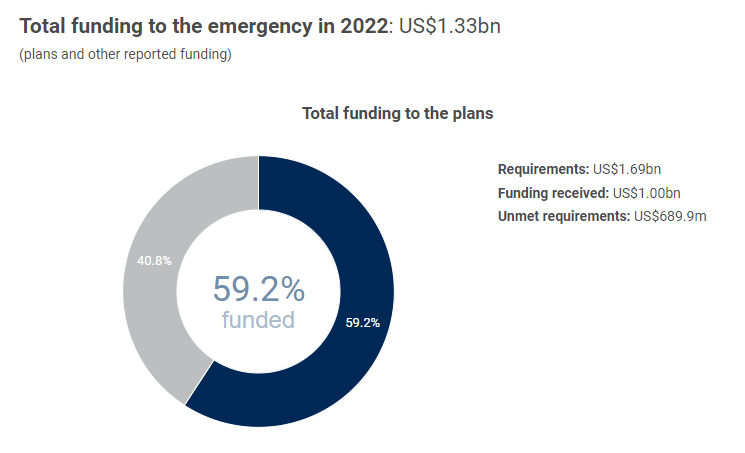

The aid worker urged governments and donors not to repeat the failures of 2021, when only 48 per cent of the humanitarian response plan in the region was funded.

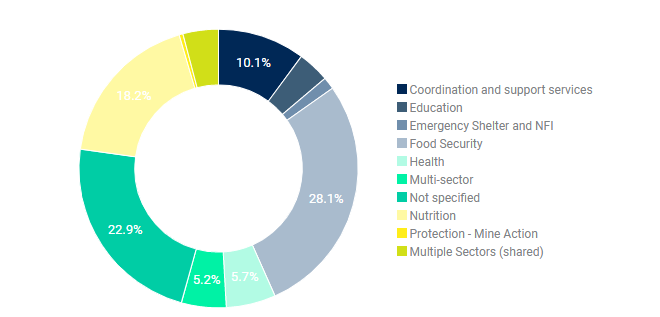

In Niger’s Humanitarian Response Plan 2022, $99.6 million is required to fund nutritional services; only $12.3 million has been covered so far. Meanwhile, aid actors have received only 8.9 per cent of the country’s $552.6 million funding requirement needed for humanitarian response throughout 2022.

Whereas the sudden humanitarian crisis in Ukraine has seen the country receive 59.2 per cent of the $1.69 billion emergency aid funding. This is apart from the country’s regional refugee plan and flash appeal put at $1.14 billion and $550.6 million respectively.

There is no humanitarian response plan that covers the crisis in Northwest Nigeria, although some humanitarian organisations, such as MSF, have scaled up investment in nutrition in Katsina State amid dwindling government funding and economic meltdown in the state.

Yet, the World Food Programme (WFP) has warned that the scale of the impending food and nutrition crisis in Niger and Nigeria is mind-boggling.

“Aid actors have agreed on the gravity of the situation, but it remains to be seen what resources will be made available to address it,” Bouabid said.

“It’s also important to keep in mind that it can take several months for foodstuffs and therapeutic foods to be ordered and delivered.

“But, from June onwards, significant numbers of children will be arriving in nutrition units. Funding for these plans and organisations will, at least in part, inform the timely distribution of appropriate food aid.”

Why malnutrition must be combated

Experts have argued that having a huge number of malnourished children could lead to lost investment in human capital associated with preventable child deaths.

“The economic viability of a country largely depends on its human capital and optimal child nutrition is key to harnessing this,” Blessing Akombi-Inyang, a maternal and child health expert, said in an interview.

According to the World Bank, one per cent loss in adult height due to childhood stunting is associated with 1.4 loss in economic productivity.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter