DR Congo: Children, Women Bear the Brunt of Escalating Conflict

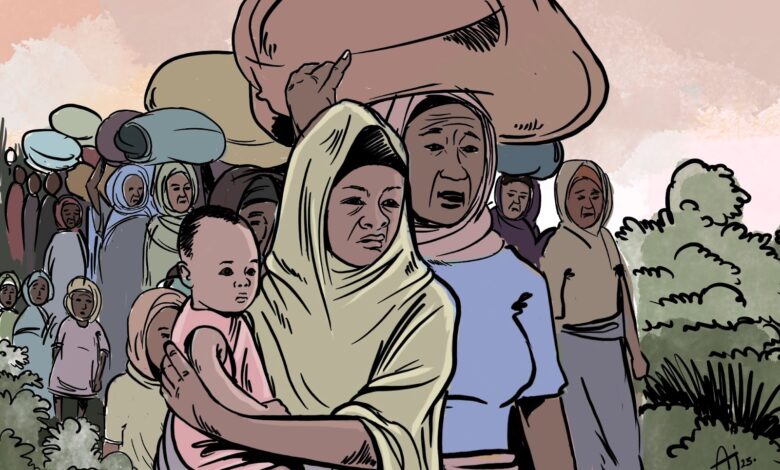

Amid relentless fighting in the Democratic Republic of Congo, millions are displaced, and children endure hunger, exploitation, and disrupted education, as humanitarian aid struggles to reach those in need.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has plunged deeper into crisis following the occupation of Goma, the capital of North Kivu, by the March 23 Movement (M23) terror group on Monday, Jan. 27. The announcement, made by M23 spokesperson Lawrence via X, sent shockwaves across the country, signalling a major escalation in the long-running conflict.

The violence that accompanied the takeover resulted in the deaths of United Nations peacekeepers, sparking outrage from Congolese authorities. In response, DR Congo’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs condemned the killings, alleging the involvement of Rwandan forces—a claim that Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame has denied.

As the clashes continue between the M23 terrorists and the Congolese military (FARDC), thousands of civilians, especially children, find themselves trapped in an ever-worsening humanitarian crisis. According to data from the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), over six million people have fled their homes since the M23’s resurgence in 2021—the highest displacement in Africa. Families are now stranded in overcrowded camps, with limited access to necessities such as food, healthcare, and education.

A conflict rooted in historical tensions

The origins of this conflict trace back to 1994, when nearly two million Hutu refugees, including militias responsible for the Rwandan Genocide, crossed into eastern Congo. This influx destabilised the region, igniting the First Congo War (1996–1997). Rwanda and its allies invaded Zaire (now the DRC) to neutralise the militias and overthrow the brutal regime of Mobutu Sese Seko. The war ended with Laurent-Désiré Kabila becoming president. However, relations soon soured between Kabila’s government and Rwanda, sparking the Second Congo War (1998–2002)—often dubbed the “African World War” due to the involvement of several nations. This conflict left over six million dead, largely from violence, disease, and displacement.

While peace agreements eventually ended the Second Congo War, the eastern DRC remains mired in instability. The region’s vast mineral reserves have turned it into a battleground for armed groups, multinational corporations, and foreign powers. These resources, rather than fostering prosperity, have fueled corruption, exploitation, and violence, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and unrest.

Among the many armed groups operating in DRC, the March 23 Movement (M23), the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), and the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) are particularly notorious. M23 emerged in 2012 following the collapse of a peace deal between the Congolese government and the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), a primarily ethnic Tutsi militia.

The group’s leaders accused the government of failing to honour the agreement, particularly regarding integrating CNDP fighters into the national army. Backed by Rwanda and occasionally Uganda, M23 quickly rose to prominence, capturing key territories, including Goma. Despite being driven back in 2013 by a United Nations offensive, the group resurfaced in 2021, escalating violence in North and South Kivu. M23’s return has strained relations between DRC and Rwanda, with Kinshasa accusing Kigali of supporting the group militarily, further destabilising the region.

The resultant humanitarian crisis

The conflict has now reached a point where millions are in desperate need of aid. By the end of 2023, over six million people had been displaced across the country, including 1.6 million in Ituri Province alone. The recent occupation of Goma by M23 forces has further exacerbated the crisis, leaving more than 1.5 million children in urgent need of protection, according to Save the Children.

Greg Ramm, Save the Children’s Country Director in the DRC, described the dire conditions on the ground: “When there is fighting going on, electricity is off, water is off, and bullets and bombs are flying everywhere. You need almost everything. What you need first is peace, for the fighting to stop, and for those who are fighting to find a different way to resolve issues and not be fighting where people are living. But children need shelter. They need protection. They need food. They need water. They need basic safety. And they need to be with their family. People might be going about their business. And when a bomb hits or when the shooting starts, people scatter. We have seen cases of children being separated from their parents because they can’t find each other in the chaos.”

As violence intensifies, women and children bear the heaviest brunt. Women, especially those venturing out to gather firewood, are at heightened risk of sexual violence, adding another layer of trauma to their already precarious existence. Gender-based violence has become widespread, deepening the suffering of communities already devastated by war.

Meanwhile, children continue to face escalating malnutrition, disrupted education, and homelessness. The NRC estimates that more than 120,000 children have been left without shelter in the eastern region alone. With schools destroyed or occupied by armed groups, the future of an entire generation remains uncertain.

Delivering aid has become increasingly dangerous and challenging. Cindy McCain, Executive Director of the World Food Programme (WFP), warned that the recent occupation of Goma has placed humanitarian workers at grave risk and obstructed the flow of life-saving aid to those who need it most.

This concern is echoed by Greg Ramm, who described how humanitarian operations have been crippled: “Sadly, all of that work has stopped over the last few days. We know that warehouses of different humanitarian organisations have been looted. We haven’t had our warehouse looted yet, but we are certainly worried about that. Our office in Goma was hit by a bomb —fortunately, no one was hurt. But we do know partners who have had their warehouses looted, which would make it even harder for us humanitarian organisations to pick up our works when the fighting stops. But that is what we will do—we will restart our work the moment the fighting stops.”

Before the recent escalation, Save the Children had been assisting in some of the most difficult-to-reach areas, including camps in Ituri, just metres from conflict zones. The organisation had been negotiating access across frontlines to deliver aid to displaced families. However, this has no longer been possible in and around Goma since Jan. 23.

“We were able to evacuate some of our staff—both international and Congolese—just in time, before the fighting hit downtown Goma,” Ramm said. “But we have many others, dozens of Congolese staff, remaining in the city who are sheltering with their families. The neighbourhood will be calm one day. The next day, the next hour, there will be fighting. People are sheltering without electricity and water. We are trying to stay in touch with our staff and their families, but many have lost contact because their cellphone batteries ran out–with no electricity, it is difficult for people to stay in contact.”

Despite these challenges, aid organisations remain committed to resuming operations as soon as the security situation allows. Ramm expressed hope that a period of stability—however brief—could enable them to return to their critical work of protecting children and providing essential aid.

The crisis beyond the DRC

The conflict in the DRC is not an isolated issue; it is emblematic of a broader pattern of instability across Africa. In Cameroon, displaced women face systemic inequalities that deny them access to land ownership, undermining their economic independence. Similarly, in Nigeria’s northwest, a malnutrition crisis has reached critical levels, with over 30 per cent of children under five suffering from acute malnutrition, according to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). In Sudan, the ongoing conflict has plunged the nation into unprecedented levels of hunger and displacement–many finding refuge in neighbouring countries like Chad–with over 25 million people enduring acute food insecurity.

These crises are interconnected, fueled by armed violence, political instability, and climate change. The international community’s delayed and insufficient responses to these challenges risk consigning generations to poverty and despair.

Coming to the rescue

Amid the ongoing crisis, humanitarian organisations have been at the forefront of relief efforts, working tirelessly to provide life-saving assistance to affected communities.

Save the Children, which has been operating in the DRC for nearly 30 years, has focused heavily on combating malnutrition among children. According to Ramm, their efforts extend across the health sector, where they support government-run health centres by providing nurses, doctors, and healthcare workers to assess malnourished children, track their growth, and administer essential treatments—whether through nutrient-rich food or critical medical interventions.

“We also have been supporting families with livelihood, with planting crops, and doing all the things that are needed to ensure that children have good nutrition. We’ve been doing that quite intensely in South Kivu, in North Kivu, in Ituri Province. Going around Goma,” Ramm said.

Similarly, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been crucial in addressing the region’s public health crises. In North and South Kivu’s Mivona health zone alone, the organisation has treated over 20,000 cholera patients, administered 126,000 vaccinations, and provided care to more than 22,000 survivors of sexual violence, including nearly 17,000 emergency interventions. The organisation has also conducted 1.5 million medical consultations, treated over 30,000 measles patients—one-third of whom were in displacement camps—and delivered life-saving care to nearly 20,000 children suffering from acute malnutrition.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has focused on epidemic preparedness and response, particularly through its Community Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness Programme (CP3). In Équateur Province, the ICRC has trained over 1,000 Red Cross volunteers in epidemic control and community-based surveillance. These volunteers help detect and report suspected cases of Mpox, encourage affected individuals to seek treatment, and work to reduce the stigma surrounding the disease. Their efforts have been instrumental in curbing the spread of Mpox and fostering community resilience.

Funding shortages

Despite ongoing humanitarian interventions, funding shortages remain a major obstacle to addressing the crisis effectively.

“There is never enough,” Ramm noted. “There is never enough collectively, even for all the agencies put together. In 2024, only half of the collective humanitarian need in Congo was funded. It was a lot of money, but it was not enough. There is not enough money right now–from donors, from the international community, and from individuals to meet all the needs. And it is essential that people of goodwill could step up and do more.”

Ramm explained that these funding gaps have far-reaching consequences: “When there isn’t enough funding, there are gaps in healthcare. You can’t support all the health issues. When you go into a health zone, you have to pick health centres to work with. You can’t help them all. When you are distributing food, there is not enough for everybody. So, you have to come up with a targeting strategy even when everybody is hungry. We set up friendly spaces in the camps to help children have a bit of normal life, to have a bit of play, and to be with friends in the displacement camps. But there are not enough resources to have spaces for all the children. There is so much need, more than anything is the need for peace. It is very difficult to move forward with development, with planting fields, with having a job in rural areas, in urban areas if there is no peace. And that is what eastern Congo needs more than anything else.”

Ramm also appealed to donors and the global community, urging them to step up their efforts: “To all donors, please do more. We know that there are enough resources in the world to take care of those children who are hungry in Congo and elsewhere–in Sudan, in Maiduguri. What is required is that people prioritise the humanitarian needs of families, of children, of those brothers and sisters around the world.”

As the crisis deepens, the funding gap continues to widen. In 2025, the humanitarian community in the DRC will require $2.54 billion to assist 11 million people, yet only 41 per cent of this amount has been secured. The funding gap hampers critical interventions, including healthcare, education, and food security, leaving millions without the support they desperately need.

What needs to be done

According to Ramm, the long-term impact of ongoing conflict and insecurity in Eastern Congo, which has disrupted the education of millions of children for over 30 years, is dire. If the violence persists, millions more will be denied the opportunity to learn, and this will have profound consequences.

He emphasised, “To mitigate this, the root causes of the conflict have to be addressed. We need to find long-term solutions to these underlying problems so that the conflict does come back year after year. And it is only with those solutions development can take place, that children can get an education, and they can grow up safe, away from war. We know it is possible. We have seen parts of Africa, parts of the world that were previously at war, where peace has come, where development has come. And we see what is possible with good governance. With good use of resources. With the end of the conflict. That is ultimately what is required.”

Amnesty International echoes this sentiment, urging justice and accountability. The organisation calls for the investigation, prosecution, and punishment of perpetrators of crimes under international law. Survivors and victims deserve justice, truth, and reparations to acknowledge their suffering and foster reconciliation. The global human rights advocacy organisation also stresses the importance of addressing the root causes of the conflict, including historical grievances, ethnic tensions, and resource exploitation.

“The first message to the international community is please, we don’t want to waste resources, so please help bring the warring parties, whatever you do, to negotiate peace,” Ramm added.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is facing a severe crisis as the March 23 Movement (M23) occupies Goma, escalating violence and causing significant humanitarian distress.

This conflict, rooted in historical tensions dating back to refugee influx post-Rwandan Genocide, has displaced over six million people, leaving many, especially children, in dire need of aid.

The ongoing conflict has led to rampant sexual violence, disrupted education, and critical shortages of essentials like food and healthcare. Humanitarian organizations, although striving to provide aid, face challenges due to funding shortages and safety risks.

They emphasize the need for peace and long-term solutions to address the conflict's root causes and promote stability and development in the region.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter