Displaced Women in Nigeria’s North East Struggle With a Severe Mental Health Support Shortage

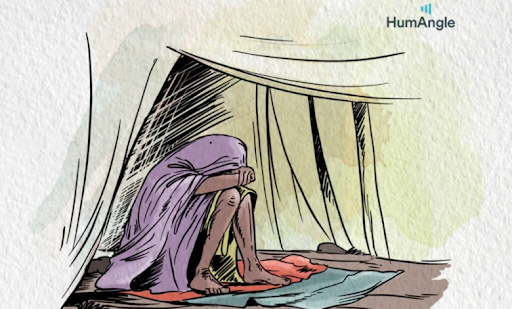

For some women living in displacement camps in northeastern Nigeria, mental health is a luxury out of reach. They carry layers of unresolved missing children, lost spouses, loved ones killed, and memories that resurface without warning.

When the terror reached her village, Maiwa, Amina ran with nothing but her two youngest children. As the gunfire echoed through the trees, they fled towards Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, North East Nigeria. On their way, she lost her 10-year-old son.

Many years later, she still doesn’t know where he is or whether he is still alive.

It has also been three years since she last heard from her husband, a firewood seller who left for work in the nearby bush and never returned.

“Sometimes, I just sit and think about them until my head hurts. I see them in my dreams, and I miss them so much,” she says, staring into the blank space in the camp.

Amina is one of thousands of women in Borno State who survived the Boko Haram insurgency, which started over a decade ago, and now live with its invisible scars: the trauma, anxiety, and despair.

The insurgency, which has resulted in mass displacement and tens of thousands of deaths, may have eased in some communities, but a battle for peace of mind remains.

The unseen effect

One in five people living in conflict-affected communities suffers from some form of mental disorder, such as depression, post-traumatic stress, or psychosis, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

In Borno State, where entire communities have been uprooted and families shattered, those numbers are likely even higher. Between January and December 2022, more than 16,500 patients received specialised mental health care services, and roughly 176,000 people benefited from psychosocial support in Borno alone.

Mental health experts in the region say the scars are deep but largely unacknowledged. Clinics and humanitarian agencies often treat physical injuries and malnutrition, but emotional suffering rarely makes it into any official register.

Another woman bearing these unspoken burdens is Halima Saleh.

Halima, now in her thirties, used to live in Maiwa, the same community in Borno’s Mafa Local Government Area where Amina lived, before she was displaced. Eight months pregnant at the time, she fled with torn clothes and her three children. “We just ran without knowing where our destination was, because there was shooting everywhere,” she said. Her eyes were watery, glazed with fear as she recounted the incident. As they fled, her husband was shot by the terrorists. There was no time to mourn; she and the children had to keep running, leaving his body behind.

The exhaustion, terror, and physical strain of the escape triggered premature labour, and her baby died shortly after birth. “I always think about the child and that horrible experience,” she whispers. “Sometimes I imagine what life would have been like if these [terrorists] had not invaded our residence.”

Just like Amina, Halima’s story mirrors that of many women in Borno, including Fatima Dije, a hard-working elderly woman full of stories and love for children.

Years ago, in Konduga, Fatima’s hometown, terrorists invaded her residence in search of male children. They found her 12-year-old son and shot him right in front of her. “He was my firstborn,” she says with a cracked voice. While fleeing their community in Konduga, she became separated from her husband and has not heard from him since.

“Since that day, I keep having flashes of the incident.”

All three women now live in Sabon Gari Camp, located in Maiduguri.

They share small tents, surviving on irregular food distributions and aid from humanitarian organisations. Beyond that, what they also share is restlessness, sleeplessness, and moments of flashbacks that come without warning.

“Even when I sleep, I’m constantly thinking of how to feed my children,” Halima said.

A lurking crisis

“They have witnessed terrible things no one should ever see: the loss of children, spouses, homes and more. Without sustained psychological care, these symptoms can linger for years,” said Fatima Yusuf, a Maiduguri-based consultant psychiatrist.

“What we notice is that trauma here often shows up as physical pain, such as headaches, heart palpitations, and constant tiredness, and this is because people don’t have the words or cultural language for mental distress.”

The humanitarian crisis in Borno State is among the world’s largest, with approximately 1.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs).

However, mental healthcare remains grossly underfunded and limited. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has provided psychosocial services, including psychological first aid, group therapy, counselling, and psychiatric assessments, to around 10,000 conflict-affected individuals in Borno over several years

In recent times, the WHO and the Borno State Ministry of Health have tried to integrate mental health and psychological services into primary healthcare, training over 200 professionals across Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe, but access remains extremely limited.

A 2019 study by scholars at the University of Maiduguri found that more than half of IDPs in the city showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

Yet only a small number had received any form of counselling or medication so far. Many rely on religious or traditional healers or on silence. “It is all destined to happen; our help only comes from God,” one woman lamented.

In many displacement camps, survivors, especially women, do not see the weight of these illnesses in comparison to the physical pain they feel. Aid workers describe how survivors use phrases like “my heart is heavy” to express mental or emotional distress.

Their grief is compounded by poverty; many have lost husbands to conflict, leaving them as sole providers for children in places with little opportunity.

‘Home reminds us of death’

Two years ago, the Borno State government began closing some displacement camps as part of a resettlement plan meant to encourage returns to ancestral homes. While others returned, some are still reluctant to go back, especially as those who have returned have been killed, and others have been displaced again due to renewed attacks.

“They tell us to go home, but home reminds us of death. My house is there, but my son is not; it only reminds me of the place where he died,” says Fatima.

Halima is also terrified of the thought of going back to her hometown, as it only reminds her of the struggle she passed through while fleeing danger with her children.

Sudden closures, according to the consultant psychiatrist, risk deepening trauma for an already fragile population. Without sustained counselling and support, relocation can reopen wounds rather than heal them.

The emotional toll extends to children who have grown up in displacement camps. UNICEF reports that prolonged exposure to conflict and insecurity can lead to lifelong psychological and behavioural challenges for young people.

In 2021, UNICEF, working with the European Union, provided community-based psychosocial services to at least 5,129 out-of-school, conflict-affected children in Borno, under a safe-spaces and resilience programme. Other institutions, such as Future Prowess Islamic Foundation School, are trying to use play therapy to help children in the region overcome the trauma of experiencing insurgency and have since impacted over 400 children.

Despite these efforts, the scale remains too small compared with the need.

Without early intervention, experts like Dr Fatima Yusuf warn that today’s traumatised children risk becoming tomorrow’s troubled adults. For some of the women and their children, healing remains distant but not impossible; faith and resilience have continued giving them the hope to keep pushing. “We crave inner peace in the chaos within,” some of them said when asked about their hope for the future.

Amina and Halima, women from Borno State, Nigeria, are among thousands affected by the Boko Haram insurgency, leading to family separation, trauma, and mental suffering. Despite surviving physical threats, they, along with others, live with relentless mental scars, facing anxiety and flashbacks without adequate psychological support. The conflict has exacerbated mental health issues in a region where one in five suffers from disorders like depression and PTSD, according to WHO, highlighting the severe shortfall in mental healthcare.

Despite initiatives to integrate mental health services into primary care, support remains sparse due to underfunding. The closure of displacement camps adds stress, with many reluctant to return home due to past traumas and ongoing conflict threats. Children in these camps face additional risks, with agencies like UNICEF providing psychosocial services, though the scale still falls short of the need. The situation underscores the risk of unresolved trauma and its potential long-term impacts on generations.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter