Displaced Families in Benue Risk Everything to Bury Their Loved Ones

One often overlooked consequence of conflict and displacement is how it erodes cultures and traditions like burial rites. Mourners in Benue State, North-central Nigeria, are defying danger to return to ancestral villages and lay their dead to rest, honouring tradition in the face of terror.

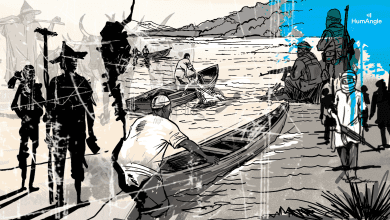

At dawn, a small convoy snakes through Kwande, Benue State’s dusty backroads in North-central Nigeria. A police siren pierces the stillness, clearing the way for mourners escorting a coffin to a place they once called home. Some ride motorcycles; others squeeze into two cars. They are not heading to a cemetery, but to a ghost village abandoned to violence.

It is the final journey of Ordue Terfa*, a 52-year-old farmer and civil servant who died in February of a heart attack. “He was going through tough times; his displacement worsened it,” Ya Adi, a close family friend, tells HumAngle.

Ordue had been struggling since losing his wife to a prolonged illness five years earlier. Left alone to raise their seven children, the widower leaned heavily on farming to support their education and welfare. His job at the state’s Ministry of Education provided a modest income, but it was far from enough to meet the family’s growing needs.

Three children attended boarding schools in Gboko and Adikpo, major towns in Benue State; the others were enrolled in primary schools. One had just completed secondary school.

But life became even tougher in March 2024 after suspected armed herders attacked and displaced residents of his village, Mbaav, in Kwande Local Government Area (LGA) — the very land where he farmed. Several people were killed in a series of such attacks on the community. His work station in Sankera, Ukum LGA, was also experiencing waves of violence, and with the growing insecurity, he eventually stopped going to work altogether.

Ordue was displaced to Jato-Aka, a remote town in Kwande, about 48 kilometres from the Cameroon border. There, he struggled to rebuild a semblance of life. He visited Gboko once in a while to check on the children.

On a Tuesday evening in February, he returned from a local market, where he had gone to buy goats in hopes of starting a new livelihood. With no access to his farmland and meagre salaries, livestock trading seemed like an alternative.

“He slumped and died in the bathroom while trying to freshen up that day,” Ya recounts.

Until his death, Ordue was assisting HumAngle as a fixer, providing invaluable access to sources and insights on the armed attacks devastating farming communities in his region. We met face-to-face in December 2024 and maintained contact through an intermediary in January, underscoring his commitment to shedding light on the crisis.

The dead must return home

In Benue, where violence has uprooted tens of thousands, the living may flee. But for many, the dead must still return home.

Traditionally, burials are never hurried in Mbaav and several other parts of the state. They are not merely rituals but communal farewells, rich with songs, storytelling, and sacred customs. It is not uncommon for weeks, even months, to pass before a body is finally laid to rest.

Overnight vigils, known as ku tsan, are central to Tiv mourning practices. The Tiv, the majority in Benue and who inhabit 14 of its 23 local government areas, gather around grieving families to keep vigil through the night. Visitors come and go, sharing food, stories, and silence. Hymns and traditional songs hum in the background, weaving a rhythm into the mourning.

“The vigils usually feel like a market square sometimes,” says Aondowase, a local who preferred to give only his first name. “People come, some to mourn, some to reconnect, some to sell or share food. It’s about being present.”

But this tradition is increasingly challenging to maintain. Armed groups have laid siege to rural communities in Benue for decades, killing thousands and displacing many more, who now live in over 41 displacement camps and host communities, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Entire villages, like Mbaav, now lie in ruin.

“Some people don’t even have graves; they died during the attacks, and their bodies were never recovered. Some are buried in mass graves,” says Aondowase, who is from Guma, the hardest hit local government area in the state, according to IOM.

Between 2024 and 2025 alone, more than 6,896 people were killed in such attacks across Benue, according to Amnesty International. The state now hosts over half a million displaced people, many living in overcrowded camps under harsh conditions. The numbers have only risen since.

For Ordue, only one vigil was held, the night before the burial in March, a month after his death.

According to Ya, who attended the funeral, the turnout was significant. But the vigil was not held in his village. It occurred at a deserted local government primary school compound, about an hour from Mbaav. “We chose the location because there’s a security checkpoint nearby,” she explains. “Even then, we were still afraid.”

The following morning, after a short service led by his local pastor, Ordue’s body was transported in an ambulance, accompanied by two cars, a few motorcycles, and a security escort. Only two of his teenage children, the eldest daughter and son, made the final trip.

“Most of us stayed back,” Ya recounts. “The interment was brief. They returned very quickly.” Ordue was buried next to his wife; his family took the risk to keep that tradition. His family members and some youths, accompanied by security forces, had gone days before to prepare the grave.

Aondowase experienced something similar when his grandfather died in 2021. The 75-year-old, a respected farmer in Atsen Yev, Guma Local Government Area, had fled the village in 2019 after armed men razed his home and several others. He resettled in Gbajimba, the local government headquarters, about 40 minutes from the state capital, where life felt safer, though uncertain.

“Many people in Atsen Yev and other villages in Guma have relatives or homes in Gbajimba, so they run there when attacks worsen,” Aondowase explains.

His grandfather stayed there with his wife and extended family until his passing.

“He was the eldest man in our family,” Aondowase tells HumAngle. He declined to share his grandfather’s name. “It is culturally wrong to bury anyone away from their ancestral home, especially an orya [the head of a household]. So we couldn’t bury him in Gbajimba.”

This is because, among the Tiv, the burial site is more than a final resting place; it is a vital marker of identity and lineage. According to studies by Andrew Adega and Franca Jando from the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, Benue State University, Makurdi, a Tiv person’s grave in their ancestral village confirms their indigeneity and ancestral ties.

“This attitude explains why the Tiv go an extra mile to ensure the graves are marked for easy identification and remembrance,” the researchers state.

This belief is slightly common among other ethnic groups in Benue, like the Idomas, Igedes, and the Etulos, who live mostly among the Tivs in Buruku and Kastina Ala LGAs.

“Anybody who dies will be buried within the family compound,” Dennis Olofu, an Idoma cultural scholar, states. “Furthermore, any Idoma person who dies anywhere in the world must not be buried outside unless someone who is a teenager or a soldier killed in the warfront.”

Returning to Aondowase’s village was no easy feat. Atsen Yev remained deserted, with sporadic ambushes still reported in the area. “We couldn’t hold the vigil there, so we held it in Gbajimba instead,” he recounts.

This adaptation, relocating vigils to safer towns, has become the new normal for many displaced families. Though stripped of their full traditional expression, these ceremonies still carry deep emotional and cultural weight.

What is unfolding in these Benue communities mirrors a broader pattern across Africa, where conflict disrupts local customs, including funeral rites. During the two-decade Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency in northern Uganda, communities were forced to abandon traditions — no body washing, no overnight vigils, no proper grave orientation. Only after peace returned did families exhume and rebury their loved ones to restore spiritual order and communal identity.

Studies and interviews that HumAngle has conducted show that similar customs in other conflict-affected regions, especially in southeastern Nigeria, have been affected, underscoring that this cultural rupture is not isolated but part of a wider, continent-wide crisis of community and memory.

Because of Aondowase’s grandfather’s influence in the area, the family could secure a police escort. “That’s how we managed to bury our father,” he says, adding that not everyone travelled along. Several other families who spoke to HumAngle noted the same: as with Ordue and Aondowase’s grandfather, not all mourners accompany the deceased to their ancestral resting places.

However, not every family can afford to hire security, so they rely on local youths for protection. They are armed only with farm tools like machetes for self-defence.

Traditionally, after the burial, the family gathers in the compound — sometimes near the grave — for a reflective conversation, ku oron, akin to a post-mortem, though without the body present. Now, many displaced families hold these gatherings in their host communities or within IDP camps after they’ve returned.

“It’s a difficult experience,” said a native of Katsina-Ala LGA, who asked to remain anonymous due to the issue’s sensitivity. When his mother died, the family had to pay both police and vigilante groups to serve as an escort so they could “bury her beside her husband in the village.”

The elite are not spared. When Mike Utsaha, a prominent legal scholar and civil society official, died in March 2023, it took the “deployment of well-armed soldiers along the route and in surrounding bushes” to convey his remains to Mbabai, his ancestral village in Guma, according to Chidi Odinkalu, a Nigerian human rights activist and Mike’s friend, who attended the funeral.

Even then, not all mourners made the journey. Some stayed behind after the funeral Mass in Makurdi.

“A capacious country home belonging to Mike’s dad, a retired judge, had been burnt twice over in attacks reportedly perpetrated, the villagers said, by armed herders. All the mourners could do was linger in the village long enough for the body to be laid into the ground before everyone scampered, grateful that there were no atrocity incidents,” Odinkalu recounts.

Similarly, when former Nigerian senator Joseph Waku died in 2019, his funeral Mass was held at a church in Makurdi, the Benue State capital. Only a few mourners, escorted by security forces, accompanied his remains to his village, Uvir in Guma. A family friend familiar with the arrangements said the then-Governor Samuel Ortom, himself from a conflict-ridden community, played a key role in providing security for the burial.

Aondowase, whose hometown, Asten Yev, lies near Mba Begha, the former governor’s village, says travelling there without security is unthinkable. “It is risky,” he says.

While many of those HumAngle spoke with could not recall specific attacks targeting funerals in their areas, the fear lingers. In the region’s volatile context, such violence is never far. On March 27, suspected armed herders stormed a funeral in Ruwi, Plateau State, killing more than ten mourners.

Since returning from Ordue’s funeral, Yav admits she struggles to sleep some nights.

“Where I live is relatively safe; we’ve never experienced an attack. But the stories I heard on the trip still scare me,” she says. “People are attacked and killed in their sleep.”

‘We can’t seem to catch a break’

Meanwhile, attacks in Benue State continue to escalate.

Recently, a group of missionaries serving in Aondona, a village in Gwer West LGA, were forced to shut down the two schools, hospital, and parish they operated. They have since relocated out of the state following a series of attacks between May 22 and 25. “Some of them [the missionaries] spent their nights in the bush alongside patients and students,” reported The Catholic Star, a local newspaper. Over 23 people were killed in the attacks, according to the state government.

Several residents who spoke to HumAngle said at least one community in the state experiences an attack nearly every day. “We can’t seem to catch a breath. Communities are constantly on the run; some are unable to plant this rainy season,” says Antipas Shomwua, the Kwande LGA coordinator of Stefanos Foundation, a humanitarian organisation.

“These killings are unacceptable. I will not sit idle while our communities are turned into killing fields,” Governor Hyacinth Alia said in a statement on June 2. “I have ordered joint security forces to immediately move into the affected areas and beyond […] and restore peace.”

Olufemi Oluyede, Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff, visited Benue State on June 3, meeting with the governor and troops. He also visited some affected communities and ordered the deployment of additional forces. “The [army chief] has come not only to assess the situation personally but to take decisive action,” Alia said after the meeting.

Although the resettlement of displaced persons from camps back to their ancestral homes within 100 days of his tenure was a key pledge during Governor Alia’s 2023 campaign, the promise remains unfulfilled due to the unrelenting violence. In November 2024, HumAngle spoke with some displaced people who have lived in IDP camps for over a decade. They expressed a strong desire to return home but voiced uncertainty about the government’s plans, especially following the launch of a new “mega IDP camp”.

Shomwua, who is also a local security analyst, warns that the continued failure to resettle displaced persons could fuel future communal conflict between IDPs and host communities, as growing populations and limited resources might increase tensions. Many camps are seeing a surge in numbers, with more displaced people and hundreds of births recorded.

“These people need to return to their homes; they need to get their lives back,” Shomwua says.

But home is not safe for them. For now, only the dead can stay at home.

*The asterisked name is a pseudonym we have used at the request of the deceased’s family to protect his identity.

At dawn in Kwande, Benue State, Nigeria, a convoy carries Ordue Terfa's coffin to his abandoned home, marking the end of a life marred by displacement and violence. Once a farmer and civil servant, Ordue was forced from his village by armed herders, exacerbating his struggles until his untimely death. Mourners face dangers to honor burial traditions, as violence in Benue disrupts funeral rites. Displaced communities adapt by relocating vigils to safer towns, reflecting a broader trend of disrupted traditions across Africa due to conflict.

Despite efforts to restore peace and resettle displaced persons, the violence persists, leaving many in IDP camps and underlying tensions unaddressed.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter