Displaced Children From Anglophone Cameroon Being Exploited Not Educated

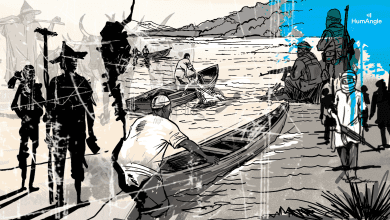

Seven years into the crisis in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon, internally displaced children are providing cheap labour in host cities and watching their educational dreams being crushed.

Instead of going to school, Claudette hawks locally prepared yoghurt and puff-puff rolls on the streets of Douala, Cameroon’s largest city.

The only reason the 13-year-old is in the city, hundreds of kilometres away from her home in Cameroon’s Northwest Region, is because she was promised she could continue her education which had been brought to an abrupt halt.

Claudette’s home village of Tatum has been wrecked by a seven-year-long crisis initiated by separatists, terrorists who want two majority-English-speaking regions to break away from the rest of the French-speaking country.

Six years ago, Anglophone militias ordered schools close across the regions near Cameroon’s eastern border, or they would face violent reprisals.

When she was only 9, a relative convinced her parents she should be sent to Douala. Claudette could attend school there and not miss any more of her education, they hoped.

But the family she stays with had other ideas. They sent her out to work.

School boycotts

The United Nations says more than 700,000 children from the two English-speaking regions were forced out of education in 2017 when the separatists made their school boycott demand.

The UN’s humanitarian arm, OCHA, says over 200,000 children who left the Northwest and Southwest regions in order to continue their education are now not in school.

A study conducted in Douala by the charity Street Child found only 31 per cent of internally displaced children were attending school regularly.

The study also revealed most children surveyed were living on the street, in abandoned houses, under bridges, and some were in orphanages.

Promises broken

At first, Claudette and her family couldn’t afford to move from their home when the crisis worsened in 2017. A distant relative negotiated a deal between her parents and a friend in the Deido area of Douala, they would send her to the economic capital of Cameroon.

It was agreed she would continue school.

“I want to become a nurse. I want to help my mother and heal her…that’s why I want to go to school,” said Claudette.

But her hopes of beginning secondary school were crushed when her host kept sending her into the street to hawk food. She hasn’t been to school in all the time she has been in Douala.

“My uncle said I will go to school but my auntie says I should sell yaourt and gateau, so that we can make money. I want to go to school but auntie says that I should wait,” she said.

Taking advantage

Regina Etaka has been working with internally displaced women and girls in the Mabanda neighbourhood in Douala. Her organisation, Bringing Hearts Together (BHeT), has assembled some of these young girls who came from homes where they were exploited and provided them with a start-off capital for petty trades to empower them.

“Most of these children, when they come, they are attached to some of these people in order to have their daily bread. They are desperate hence they find themselves in these homes,” she explained.

“Their hosts take advantage of the fact that they are desperate and take them for granted. After exploiting them for years, some were sent away and had to sleep on the street. We had a case where this young girl was sent away at an ungodly hour and she was sexually assaulted,” Regina says.

Social worker Josephine Nsono said the situation is made worse by the fact that most of the exploited children she sees have lost contact with their families.

They do not have a contact number for them, and in many cases, after the children left, their families were forced out of their homes by the conflict. The children do not know where their parents or older siblings are.

This allows the exploitation to continue, and the hosts go unpunished.

Vulnerable

“For the ones I have been working with, they barely know the contacts of their primary caregivers. They only have contacts of families they are living with, which means they can’t even report to their primary caregivers.

Once these cases are reported, we handle them. It is unfortunate that many do not report and don’t seek help,” she said.

Nsono also lays blame on parents who enter undocumented negotiations with their relatives over the future of their children. Claudette’s case is one amongst several where children were taken to cities without official agreement or documentation recording the commitment and promises between parents and the children’s hosts.

This leaves children vulnerable to abuse.

“We have this case at hand where this girl has been raped twice. These children are exposed to different ills and forms of violation. This is not acceptable, the law doesn’t permit that,” Nsono said.

Claudette herself has not been able to reach her parents back home to explain what she is going through. She heard they were forced from their home by a military raid, and she doesn’t have any way of contacting them.

“I want to go back to my village and stay with my parents,” she said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter