Displaced By ‘Bandits’ (1): Nigerian Refugees In Niger Are Not Eager To Return

The situation in Nigeria is so bad, tens of thousands of its people are travelling long distances to find solace in another increasingly unsafe country.

When Nigeria became too distressing for Abdullahi, he gathered what remained of his valuables, travelled hundreds of kilometres towards the north, and sought refuge in the neighbouring Niger Republic. He has since not looked back.

One Thursday evening in June, Nigerian refugees at the Chadakori displacement camp gather under a large Neem tree to receive visitors from their home country. The crowd, consisting almost entirely of men, grows bigger as introductions are made. Eventually, children assemble nearby. Wives and mothers watch the proceedings from a distance, not straying too far from their shelters. The curiosity on their faces suggests they do not host delegations like this one often, and it is easy to see why.

Though both Sabon Birni in Sokoto, Nigeria, and Maradi in the Niger Republic are considered border communities, crossing from the former to the displacement camp takes not less than two hours of bumping through dusty roads. It also requires stops at numerous security checkpoints where travel permits are verified.

After the camp administrator’s speech, the men rise one after another and volunteer to share how they have come to settle here, miles away from home. Abdullahi, wearing an oversized, short-sleeved blazer and a black net cap, is the sixth to speak. Terrorists, often described locally as bandits, had attacked his home community of Dansadau, Zamfara State, last August. He remembers it was a week after the annual Islamic festival, Eid-ul-Adha.

“They previously assured us that they were not after us. What we didn’t realise was that they had raided one town and killed 15 people before coming to us,” he narrates.

“We fled to Dan Gulbi, where the village chief lives, as soon as we learned of this. We went back after about a week. They inquired as to our purpose for visiting, and we replied that we had come to cultivate the land. They said we couldn’t reside there unless we paid a tax of N200,000. We searched everywhere but couldn’t raise the money. That’s how we spent a year without farming … without food.”

Luckily, Abdullahi has relatives in Danga-Zouani, a village in the Maradi region of western Niger, who informed him about a camp where Nigerians were welcome. He travelled to Garin-Kaka, a Nigerien town which itself hosts a refugee settlement, before he was moved by the authorities to his present location in Chadakori, another community in Maradi.

The trouble with Nigeria

The violence in Northwest Nigeria has many faces. On the one hand, we have the conflict between herders and farming communities over limited resources. Then there is organised crime which features kidnapping for ransom, cattle rustling, community raids, gender-based violence, and extortion. Recently, we have also seen signatures of various Boko Haram factions in the region, though most of their operations had previously been restricted to the Northeast.

The problem is worsened by widespread poverty, weak governance, illiteracy, inadequate policing, and the proliferation of small arms. Between 2011 and mid-2020, the violence had killed over 8,000 people and displaced over 200,000 others. The situation has since degenerated, giving rise to an alarming humanitarian mess.

Attacks against Abdullahi’s community, Dansadau, have not ceased since he left. There have been at least four major incidents this year, according to data gathered by the Nigeria Security Tracker. In May, nine people were killed, 18 were abducted, and hundreds of cows were rustled. Farmers have continued to receive threats. Many have abandoned their farmlands while others either hire vigilantes to protect themselves or hope fortune will continue to smile on them.

Those seeking new beginnings board a cab, bus, or truck going to the Niger Republic — ironically the least developed country globally, 28 steps behind Nigeria on the Human Development Index ranking. It is also an increasingly unsafe country. Security in the Niger Republic is deteriorating according to the 2021 Global Peace Index, which ranks it 137th out of 163 countries.

Nigeria shares land borders with four countries — Benin Republic to the West, Niger to the North, Chad to the Northeast, and Cameroon to the East. The 1,608-kilometres-long border with Niger is second in size only to that shared with Cameroon. It is touched by five of the seven states in Northwest Nigeria — Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, and Zamfara.

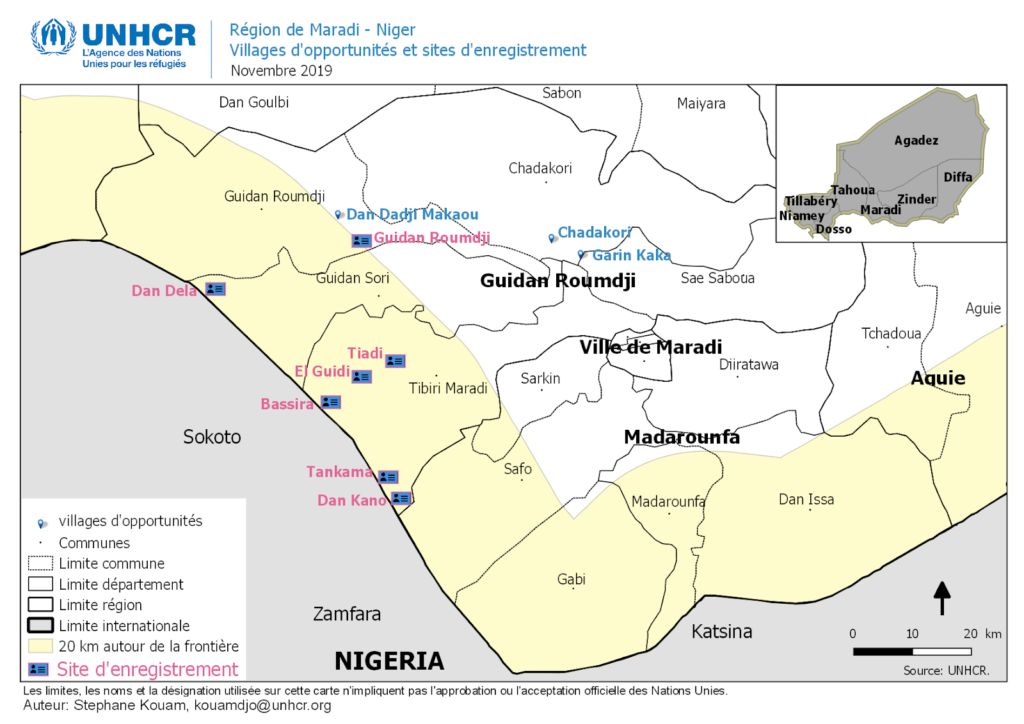

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that, as of June, at least 80,000 Nigerians, mostly children and women, had fled to Maradi, one of Niger’s several regions and its second-largest city. The movements which started in late 2018 forced the UN agency to open a regional sub-office two years ago to coordinate humanitarian services. While the UNHCR has registration points closer to the border with Nigeria, aid is provided in areas designated as Villages of Opportunity such as Chadakori, Dan Dadji Makaou, and Garin Kaka. Refugees are often relocated from the border towns to these camps, which are situated further into the region to ensure their safety.

Migration between Nigeria and the Niger Republic is easy because, aside from geographical proximity, the communities share a lot in common. Over half of Nigeriens are Hausa and the country has significant Fulani and Kanuri populations, all of which are ethnic groups spread across Nigeria as well. So even though the country’s official language is French, as against Nigeria’s English, nationals on both sides speak at least four similar languages.

“Most of these communities see each other as one,” says security consultant Dr Kabir Adamu. “They are essentially the same communities divided by colonial demarcations and so moving from one part to the other is not seen as any big deal.”

Chadakori, where Abdullahi’s refugee camp is located, is inhabited by the Gobirawa, citizens of Gobir — one of seven city-states that made up the 14th century Hausa Kingdom. While Kano and Rano were known for cotton production and Daura and Katsina were renowned for trading, the people of Gobir were warlords who protected the kingdom from invasions. They have a long history that dates back many centuries and today have roots in the Niger Republic as well as many parts of Nigeria, including Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, and Zamfara. The Nigerian seat is located in Sabon-Birni, a Local Government Area in Sokoto that shares boundaries with the Niger Republic.

Though Nigerians are moving in droves to Maradi, the Niger Republic itself has a share of the conflict situation in the Sahel as it battles extremist violence, organised banditry, and communal clashes. As Nigerians are pouring in, Nigeriens themselves are fleeing their country in the thousands. More are becoming internally displaced. Attacks by bandits in Maradi have especially spiked this year just as on the other side of the border in Nigeria.

No longer at ease

The Chadakori settlement, which hosts the largest number of refugees in Maradi, was opened in July 2020, starting with 505 displaced people. It is a vast land housing 1,114 symmetrically lined and well-spaced tents. While the plan is for the site to host as many as 10,000 people, it had 5,698 refugees as of May this year and 5,745 when HumAngle visited a month later. Ishaq Salihu is one of them.

Salihu is from Nasarawa, a village in Sabon Birni. In one incident, two people from his community, including his brother, were shot dead by terrorists. Another young man, who was visiting for work, was shot in the legs and had to have them amputated. The criminals parade the area for valuables such as phones and cash, and when their victims have none of these, they beat them.

“The town has become their gateway to other destinations. They attack every day. Even yesterday, they went to the Imam of the town and took away his motorcycle. There used to be a lot of riches in the town, but today you can’t even find a single hen,” says Salihu. “When they couldn’t locate anything, they resorted to killing people.”

“Nothing is easy there, and all we can do is hope for the best. We hope that peace will return so that we can return because it is now time to start farming,” he adds.

He had just returned from a visit to Nigeria to see his family members and saw that the terrorists were still on the prowl. He himself fell victim. “I was struck in the head and my hands with a stick because they wanted to take my phone,” he says, removing his kufi cap and pointing to the back of his left hand to show where he sustained injuries.

All of the refugees who spoke, whether from Katsina, Sokoto, or Zamfara, had similar stories of loss and tragedy.

The father of Salihu Idrisa, who is from Tafkin Hili in Sokoto, was murdered. Idrisa was an IDP in Nigeria for a year before arriving at the Chadakori camp in Sept. 2020.

Abubakar Buda Maigari, the village chief of Dan Chigidau, fled a year and eight months ago. They had been hearing about the terrorists’ presence in surrounding communities. Then one day they struck and kidnapped four people. “We visited them late at night to hand over the ransom they demanded. But, as we approached, they shot the victim and vowed to return,” he says. “That was when we realised we could not remain there.”

Someone talks about a son of the village head in Magira, Sokoto State, who had been married for a month when the terrorists paid them a visit. They threatened to rape his wife. He resisted and was shot in the leg. He is said to be receiving treatment at the Orthopaedic Hospital in Wamakko.

Exiles at home

In contrast to what they experienced in Nigeria, the refugees find life in the Niger Republic peaceful and relatively comfortable. Mutari Saleh, who wears a brown jacket branded Commission Nationale d’Eligibilité au Statut des Réfugiés (CNE; National Commission of Eligibility for the Status of Refugees) and represents the government at the camp, explains why.

The Chadakori settlement is divided into six sections, each one assigned to a ward chief. There are committees set up to manage issues such as maintaining good hygiene. The refugees receive free meals every month. Everyone who is ill has access to free medical care that is said to include surgeries, and pregnant women can equally access maternity services. Sick people who cannot be treated in Chadakori are taken to the Gwaramawa Dispensary in Yamai.

“Apart from that, the Niger government has worked with the UN Refugee Agency and enlisted the help of non-governmental organisations to care for the refugees,” says Saleh. “We’ve been invited to come here and observe if they’re abusing their rights. Many organisations, notably the Danish Refugee Council, are supporting us. If there is a conflict between the organisations and the refugees, we as government representatives will intervene to resolve the situation.”

“Here, we’re like brothers,” he adds, to the nod of nearby refugees.

The displaced people say they get along well with the “kind” citizens of the host country and are having a great time here.

“These people embraced us in ways we could never have imagined. They dug a borehole for us and power was installed. Tents have been erected and food is distributed. If your child is ill, medication is free; costs, even up to 10 million dollars, will not be levied against you or your wife. This is why we thank them. May God bless them,” says Iliyasu Abdullahi.

Muhammad Musa, who hails from Dan Cigidau, a community in Katsina, describes his later days in Nigeria as full of horror. Before Dan Cigidau was attacked, the terrorists sent a letter daring them to prepare if they thought they were bold. When they came in Dec. 2019, they killed a young husband by chopping off his head. Only the rest of his body was found. Scared to death, the people deserted their homes. At first, they jogged to Kanwa in Zamfara State. Then they moved to Malamai, then Gidan Rigu, where they spent a year, before arriving in Chadakori seven months ago. Those who remain in Dan Cigidau are still under siege — Musa learnt that, sometime in March, all the cattle in the community were rustled by bandits. But life in the Niger Republic is much different.

“Because of our relationship with the people here, it has become more peaceful for us. Even if you have N10 million, you can now sleep soundly without fear,” he acknowledges.

One other thing the refugees are grateful for is the enrolment of their children — over 800 of them — into school. Those who are not old enough to attend have access to a playground. According to Abdullahi, “it has gotten so good that even youngsters don’t want to return home.”

Nigerian govts’ hostility to IDPs

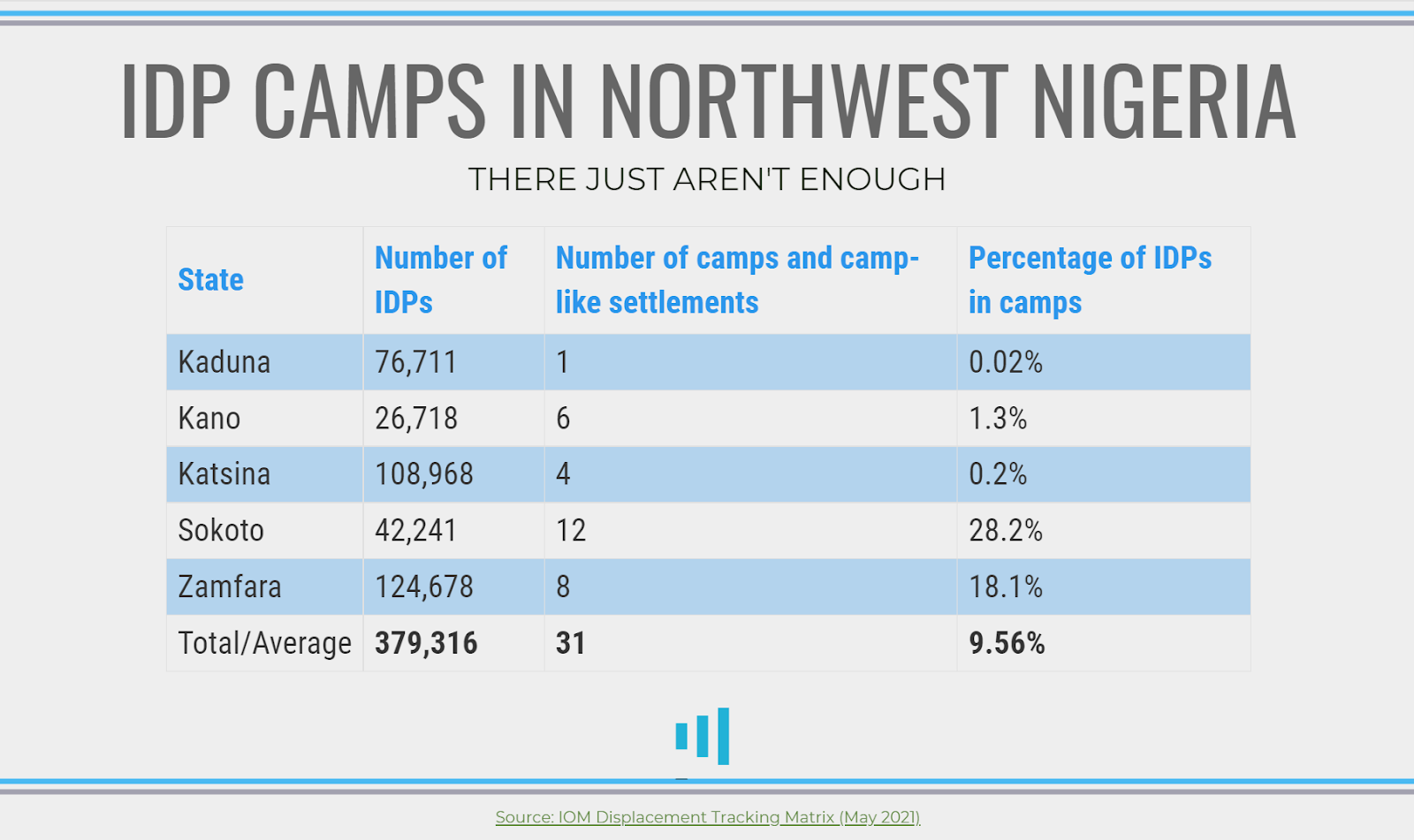

Last February, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) identified over 379,000 Internally Displaced People (IDPs) across five states in Northwest Nigeria: Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Sokoto, and Zamfara. But there are only 31 camps or camp-like settings in all the states — most of which are not formally recognised. As a result, a meagre 9.2 per cent of the IDPs live in camps compared to 45 per cent in the northeastern state of Borno and 27.4 per cent in the north-central state of Benue. The remaining people seek out shelters in different host communities.

So, why aren’t there enough displacement camps in the region to accommodate victims of terrorism? One reason is that the state governments are not very accommodating. Zamfara governor Bello Matawalle boasted in 2019 that his state had no “single IDP camp” in reaction to criticisms about growing insecurity. The following year, the government in Katsina closed down seven camps and similarly bragged that there was “no single person” in its displacement camps. The governor, Aminu Masari, warned non-governmental organisations not to visit any of the settlements, claiming that the continued stay of displaced people in camps “is what is giving [an] opening for those wanting to prolong banditry”.

Dr Adamu, who is also the Managing Director of Beacon Consulting, explains that some of the state governments avoid setting up formal displacement camps because they see them as embarrassing and “a slap on their face”. But other issues are at play as well. One, the establishment of camps is guided by frameworks used by humanitarian organisations such as IOM and UNHCR. And then, these organisations sometimes have their resources stretched thin or are bogged down by politics in the communities they operate.

Preventing humanitarian organisations from offering assistance “is not in any way helping anyone, including the government,” Dr Adamu says. “Of course, we all know that there are other third parties that capitalise on conflict to achieve their objectives. So the onus is on the government to ensure that these third parties are not allowed to gain access to the sector, that only genuine humanitarian and development workers do.”

‘We demand peace’

It is not only the refugees who believe the Nigerian government can do more to address insecurity in regions being terrorised by bandits.

Baraya Dan-Musa, an aide to the Sarkin Arewa Gobir Chadakori, for example, urges the country’s leaders to “take a position and demonstrate their strength.” Unable to understand how Nigerien soldiers are perceived to be more proactive even among Nigerian locals, Saleh, the camp administrator, thinks perhaps Nigeria’s president is not giving military personnel enough freedom to act.

“We are hopeful that the Nigerian government will take significant security measures and dispatch troops,” he says. “If there is an attack here, or if they pursue refugees to their camps, Nigerien forces will go and face them. But, as a commander, how will soldiers wait for your orders while an attack is underway? We need the Nigerian government to put a stop to this. We urge Nigeria’s President, General Muhammadu Buhari, to allow soldiers to carry out their duties.”

But while they wait for the government of their country to step in, Nigerians in the Niger Republic are going out of their way to fully integrate into the new environment. What they currently have are cards provided by the Ministry of Interior that identify them as refugees, but the Nigerien government gives them hope they could one day become more.

“If you spend some time in the country and want to register as a citizen, you must apply to the president’s office,” says Saleh. “Also, if a person is discovered to be adding to knowledge and is a hard worker, the president has the authority to declare that this Nigerian has now become a Nigerien citizen.”

Nigerien citizenship can, in essence, be acquired through a presidential decree. Also, since it was amended in 2014, Niger’s nationality code has made room for dual citizenship. And since Nigerian laws do not prohibit it either for people who are citizens by birth, refugees can become citizens of both places if they meet the host country’s requirements.

It is almost 6 p.m. and the Nigerian delegation, determined to be back in Sokoto that evening, prepares to leave. More women have gathered and when I approach they become particularly vocal, struggling to outshout each other as they pray for the violence to cease.

“We hope that peace will return to our nation so that we can go back. The country’s leaders must lead us well. We demand that peace be restored. It is not good if you are well but not peaceful. Everything revolves around peace,” says a middle-aged woman with a transparent black scarf draped across her chest. Like everyone else, she still has relatives in Nigeria.

This is part of a series of reports supported by the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) to unmask the impact of rising insecurity in Northwest Nigeria.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter