Disappearing Wetlands Making Lagos More Vulnerable To Flood—A Geospatial Analysis

Lagos needs to rethink its approach towards mitigating the impact of environmental disasters such as flooding and sea-level rise. This will require protecting wetlands from further depletion and restoring lost areas.

The rainy season in Nigeria’s economic capital, Lagos state, has become synonymous with submerged cars, homes, and commuters wading through knee-high floodwaters as the coastal city wrestles with the impact of flooding and the depletion of wetlands paving way for urbanisation as well as an appetite for affluent neighbourhoods.

Lagos’s persistent vulnerability to intense rainfall and overflowing of water onto streets is associated with numerous factors including a low lying coastal geographical feature and weak flood control infrastructure. The inability of the city’s wetland systems and Lagoon to serve as a sponge for runoff water are also contributing to the perennial flood crisis that disrupts social-economic activities.

The continuous sand filling of wetlands and conversion for housing units has impacted the ability of the natural systems to provide storage capacity and reduce the severity or frequency of flooding. Last year, the Lagos Council of the Trade Union Congress drew attention to the importance of protecting wetlands, complaining that a significant portion of the natural system had been converted to high density, unplanned residential housing spaces.

The state government also noted the dangers posed by wetlands destruction while cautioning property owners and developers in the Magodo Residential Schemes to halt development on the wetlands or face sanctions. According to a state official, the “indiscriminate development of wetlands would not be encouraged anywhere in the state as it is potentially dangerous and harmful to the environment.”

A 2013 report found that many of the wetlands in Lagos have undergone severe spatial changes from rapid urbanisation in the past decades. Although the depletion is visible on the ground, airborne sensors from geospatial platforms such as satellites provide unique data and broader perspectives on the catastrophic effects of unsustainable urbanisation.

Another vital natural flood management system in Lagos is the lagoon, a body of water close to the Atlantic Ocean. In 2017, a surge in the lagoon’s water level was linked to the flood that ravaged parts of the states including Victoria Island, Lekki, Oniru, Ajah, and Epe. The high tide was said to have slowed down the flow of rainfall water from drainage channels.

Wetlands loss and risk of flooding

Urban development alone is a contributing factor to floods. However, development in flood-prone areas such as where Lagos sits is almost like looking for trouble. Construction projects on wetlands and vegetated areas would naturally increase the vulnerability of this floodplain area to flood.

It also sets the area on the path of recurring environmental disasters that threaten public safety. Over the years, incidents of submerged communities in Lagos State have been shared online by individuals calling the attention of the authorities to the impact of flooding.

HumAngle has examined some of the highly flooded areas reported in Lagos and cross-matched these areas to geospatial data on the disappearance of wetland and vegetative surfaces.

In July 2017, the Ikate Elegushi area of southern Lagos was submerged in water after a heavy downpour. The streets were filled with runoff flowing or stagnating water lasting hours long after it had stopped raining. A closer examination of the community shows that over the last 10 years there has been an outward pattern of development that continued to replace the wetlands in the area.

Chevy View, Lekki, is another infamous hotspot for floods. The area is close to the Lekki conservation wetland resource centre. In 2016, the environment became a pond after a rain event and satellites show that parts of this could be attributed to the loss of the natural flood control wetlands in the area over the years.

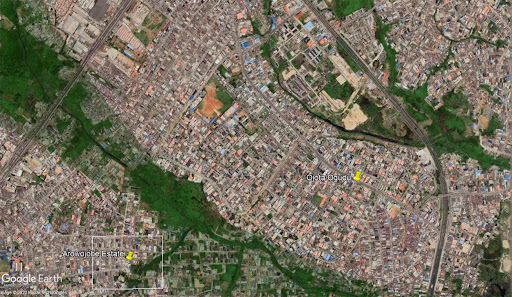

In 2019, reacting to flooding around Arowojobe Estate, Twitter user Dr Ødegaard (@fimiletoks) used Google satellite imagery to highlight his concern with developers and landowners squeezing up the wetlands in Lagos and replacing them with impervious surfaces which create runoff problems. He was reacting after seeing the video of a flooded house around.

“The land grabbers and ‘developers’ on the mainland have shifted their focus now to the plains in Ogudu and Ojota axis,” he said, adding that they were sand-filling the wetlands that drain into the Lagoon and Ogun river and urging the authorities to address the problem.

The Arowojobe estate area is yet another example of urban development heavily replacing the natural wetland.

In 2020, a video circulated on Twitter showing the surface area of the Ijora community submerged and pedestrians navigating through the flooded street.

The landscape of Ijora provides another glimpse into the pace of urbanisation. The area consists of a road network, bridges over water bodies, and a few gardens situated between buildings and other constructed surfaces mostly on the eastern extremes of the town.

The landscape has changed over the years. Satellite imagery from a decade ago shows that the vegetative reserves have been replaced by roads, the wetlands by buildings, and parts of the surrounding water bodies have shrunk due to filling to give way for construction.

Trajectory of flood risk in Lagos

HumAngle’s assessment of satellite data on wetland systems and vegetative resources depletion indicated a disturbing trend. Satellite data dating back three decades (the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s) suggests that if the trend continues, Lagos may lose, on average, 32 per cent of its wetlands and vegetative resources every 10 years.

The risks of disappearing wetland areas are even more troubling because Lagos is near the Atlantic ocean and is barely a few metres above sea level. With no natural buffers and support infrastructure, the threat of submerging could intensify due to inland and coastal extreme events.

This danger is further aggravated by the latest rainfall projections, as studies suggest that there would be increased flooding in the southern extremes of Nigeria due to the trend of increased rainfall frequency and intensity.

Strengthening resilience in Lagos

Sako Kato, a climatologist and lecturer at the University of Abuja, says protected areas are supposed to be established on wetland systems with the intent to preserve the integrity of the landscape against the risk of flood and submergence. He points out that these wetlands serve as a medium between the Atlantic ocean and land, and thus removing the wetland only invites a direct interaction between the two.

“Wetlands serve as transitional zones between the city area and the nearby water bodies. They are to be protected just like conservative green areas and the government and local authorities must restrict most forms of interference that might alter the state of the wetlands,” Sako told HumAngle.

He added that the foundation of environmental protection is to cause no harm in the first place. “Identify it for what it is [as a natural defence against flood] and protect it as it is because it is difficult to replicate its functions through artificial methods.”

The loss of wetlands also impacts the local ecosystem. Sako explained that wetlands support biodiversity and serve as home to a wide range of species.

“Once the biodiversity is gone, even if artificial methods are used to inundate the place to restore the wetland, it will not have the characteristics that made it the wetland it was before,” he stressed. “Human efforts cannot restore natural landscape conditions to the way they were and even partial restoration may only be possible after a long time and still may not be achieved in time to prevent damage caused by wetland loss.”

Building sustainable communities, robust flood management infrastructure, and strengthening the implementation of environmental laws are therefore essential to curb the indiscriminate destruction of natural systems.

Another important part of mitigating and adapting to the increasing risks of coastal and inland flooding is putting in place more proactive measures to conserve the surviving wetlands and investing in wetland restoration and preservation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter