Disappearing Migration Routes Fueling Farmer-Herder Violence in Northern Nigeria

As climate change chokes Nigeria’s grazing lands and water access, herders’ journey across five states reveals the slow collapse of pastoral life and the silence of the systems that once protected it.

Bello Ardo still remembers how they were sent away from Dapchi, a town in Yobe State, North East Nigeria.

It was 2015. He had just arrived with his family and herd, hoping to graze and rest after a long journey from Bauchi State. He approached the District Head, then the Divisional Police Officer, seeking permission to stay. But the community rejected them.

“They said, ‘We don’t want to see cattle here. We also don’t want to see strangers. Take your animals and leave our community,’” he recalled.

He moved southward to Ngamdu in Borno State, only to be met with hostility. “We went three days without water until the community leader intervened,” he said.

Bello is a herder, an occupation he inherited 45 years ago. His parents were originally from Zamfara in the North West, but migrated to Kano, where he was born. He learnt to herd cattle in the once lush Falgore Game Reserve.

By 2011, things had changed. The grass thinned, the rivers shrank, and he began migrating in search of pasture, following designated grazing routes, moving from Kano to Bauchi, then Yobe, Borno, and finally Adamawa. In each state, he made brief stops; sometimes staying just a day, and in some places up to three years. But the pattern remained the same: rejection, scarcity, and tension.

Bello is now the State Chairman of Sullubawa, a Fulbe clan known for cattle herding and spread across northwestern Nigeria. But titles mean little when the land offers no relief and the institutions once meant to support herders no longer function. The grazing routes Bello once followed stretched across the country’s northern region. They protected herders, shielded farmers, and helped maintain order.

Those routes are gone, erased by urbanisation, farmland expansion, and state neglect. In their absence, herders searching for water and grass now stray into cultivated land, fuelling suspicion, resentment, and violence.

What happened to the routes?

There was a time when the routes had names.

Older herders, like Bello, still remember them, not as lines on a map, but as muscle memory. They could list the rivers they crossed, the forests they skirted, and the wells that dotted the way.

“The Falgore Forest was demarcated by the government,” Bello said. “Locally, we call this demarcation ‘centre.’ On the west of this demarcation were farmlands, on the east, wilderness with lush vegetation. To the north, a grazing route for cattle. This leads to states like Bauchi and Benue.”

Leaving Kano, Bello arrived in Burra, Ningi, and then Tulu in Toro, all in Bauchi. Here, he spent three months in the Yuga Forest. Then he moved eastward, circling back to Gadar Maiwa in Ningi until he reached Darazo, still in Bauchi. From here, he spent the next 30 days migrating into Yobe.

He moved through Funai, under Ngelzarma town, and Dogon Kuka under Daura town, both in Fune LGA. He then travelled north of Damaturu to graze in Tarmuwa, south to Buni Yadi, east to Kukareta, and further on to Gashua and Nguru.

He said all these places have pastures but limited water, except during the rainy season.

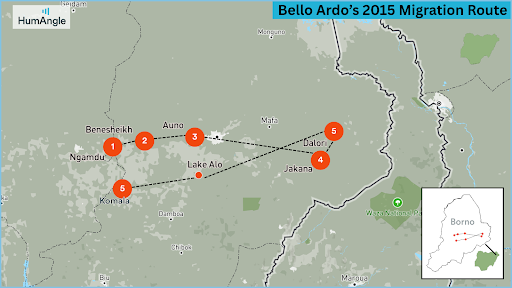

Bello left Yobe in 2015 and arrived in Borno. After initial hostilities, he grazed Ngamdu, Benesheikh, Auno, and Jakana. Then, he entered villages like Dalori around the Alau Lake in Konduga. And then he entered the Komala Forest, still in Konduga. He left Borno in 2017 and migrated to Adamawa.

These were not random movements. They followed established corridors, called burtali, designed to support seasonal migration. Marked by the defunct Northern Regional Government during Nigeria’s First Republic, burtali were official grazing routes, some stretching hundreds of kilometres. They connected water points, grazing reserves, and veterinary posts, and were governed by traditional authorities and state institutions.

Herders knew where to move and when. Farmers knew which areas were off-limits during the season. Communities in between prepared for the passing of cattle and offered rest. There was friction, yes. But it was friction with the structure. Disputes could be mediated. Violations could be punished. Movement was predictable, and conflict was, for the most part, containable.

“The easiest way to identify the route is by cattle footprints,” Bello said. “It is always busy. There are also trees like dashi [hairy corkwood] and cini da zugu [jatropha], planted on both sides. The government planted some. Farmers also plant them to protect their fields.”

“Most of those routes have become farmlands, roads, or houses,” he said. “We now migrate through tarred roads and residential areas.” Even during his migration, Bello recalled that some routes were already blocked. “In some places, I followed the burtali and others tarred roads.”

In Sokoto State, Abdullahi Manuga, another nomadic herder, confirmed that most routes have been encroached upon. “When we reach a blockage, we have no choice but to go through towns or residential areas,” he said.

This, experts say, is where tension begins. “When a route is blocked, the herder will try to find a way around it,” said Malik Samuel, a Senior Researcher at Good Governance Africa. “And in this process, animals stray into farmland or residential areas. This then leads to conflict.”

Abdullahi explained the challenge: “With over 1,000 cattle, you cannot control all of them. One or two will stray into farmlands, often leading to clashes with farmers.”

The scale of the problem is vast. In 2018, desertification degraded more than 580,000 square kilometres of northern Nigeria, affecting about 62 million people. In Yobe, a HumAngle investigation uncovered how the shrinking ecosystem has intensified competition between farmers and herders. In Sokoto’s Goronyo and Gwadabawa, pastoralists have abandoned the Rima Dam, once a key watering point, due to drying reservoirs and farmland encroachment.

The disintegration did not happen overnight. It came in stages: farmlands slowly consumed designated routes. Grazing reserves fell into disuse. And eventually, the state disappeared from the equation altogether.

“Population has grown, while resources, land and water have not,” Malik said.

He stressed that the burtali were designed to prevent this tension. “These are the only routes known to herders. The reason behind the creation of these routes was to avoid tension between farmers and herders.”

Since 2020, more than 1,356 people have been killed in Nigeria due to farmer–herder violence, according to SBM Intelligence, a Lagos-based consultancy. Amnesty International has identified the government’s failure to intervene or prosecute perpetrators as a major driver of the crisis.

Climate migration and desperation

Like Bello, Abdullahi is also on the move.

He is originally from Jangebe in Talata Mafara, Zamfara State, and has followed a path shaped by drought, conflict, and disappearance. His reason is the same.

“Scarcity of pasture, the expansion of farmlands, and continuous rustling of our cattle made us migrate,” he told HumAngle. “Most of our animals have been rustled. The bulls in our herd are barely up to five.”

Seven years ago, when pasture began to vanish in his village, Abdullahi left. He first moved into Niger State. Then, he went from Gezoji to Tudun Biri in Igabi town of Kaduna, then he returned to Kwana Maje in Anka, Zamfara State. He moved again, this time to Mallamawa in Katsina, and then re-entered Niger State. Here, he grazed the Ibbi and Wawa Forest until forest rangers challenged him. This made him move to Gidan Kare, a village in Sokoto State, before settling in nearby Dange Shuni town.

Both Bello and Abdullahi left Zamfara. While the former travelled east, through Kano, Bauchi, and Borno, the latter moved west. Their journeys trace a human map of collapse, one that cuts across nearly half of Nigeria’s landmass.

In both men’s stories, geography is memory. But it is also grief.

Bello said that across Bauchi, Yobe, Borno, and Adamawa, formerly lush plains have turned brittle, while rivers have grown unpredictable. Rain falls heavier, less often, and in bursts that flood lowland routes.

The consequences are not only ecological. They are generational.

Some herders are giving up the trade. Others are sending their children to work in towns. Abdullahi said he now substitutes herding with subsistence farming and being a shop attendant. But even this is a struggle. “he land is already full,” he said. “I have lost interest in grazing. I want to settle in one location and raise cattle on a ranch.”

For Bello, too, something fundamental is shifting.

“The migratory culture is dying,” he said. “It is dying because of the crisis and rejection, limited resources, and sudden realisation of the importance of education.”

He now believes that pastoralists must adapt.

“Many herders now prefer ranching. We want to combine our traditional knowledge and modern ways to raise cattle differently and educate our children.”

What was once passed down as tradition is now being considered for survival. The land is changing. The climate is changing. And slowly, the herders are changing too.

Farmers at the frontline

“There are several farms here that have encroached on grazing routes,” said Sanusi Salihu Goronyo, a 49-year-old farmer from Sokoto. “Owners of these farms have clashed several times with herders when their animals stray. Some farmers got these lands on lease from local government authorities.”

Sanusi has farmed in the Middle Rima Valley, near the Goronyo Dam, for over 15 years. He grows rice, onion, garlic, and wheat, alternating between rainfed and irrigation farming. He started with five hectares. But unpredictable weather has made farming harder.

“Sometimes the dam overflows and destroys our crops,” he said. “One year, we lost everything we planted; rice, onions. More recently, our onion seedlings died because the soil here could not support them.” Sanusi has since expanded his farm to 20 hectares, hoping to improve his harvests.

In Bauchi, the story is the same. “The burtali has existed for as long as I can remember,” said Kamalu Abubakar, a 32-year-old farmer from Nabordo in Toro LGA. “But many of the routes have been encroached on. Even here in Toro, people who were never farmers now farm, out of hardship.”

He said this desperation often leads people to cultivate land along migration routes. “When herders come through with their animals, it leads to clashes.”

There are no longer visible signs of the burtali. The routes have faded, not just physically, but from institutional memory. “Almost everywhere is farmland now,” Kamalu said. “A few spots are left for grazing; sometimes cattle stray into farms. But some herders intentionally drive animals into fields.”

To herders, the land is a path. To farmers, it is a livelihood. What was once shared in the vacuum left by failing institutions is now contested. What was seasonal has become criminalised.

“When this happens, people take action,” Kamalu said. This “action,” sometimes, means reporting to authorities. Other times, they confront the herders directly.

Kamalu farms on five hectares of land inherited from his father, who leased it from the government more than thirty years ago. These are not wealthy farmers. They survive on small plots. A single ruined field can mean food lost, income gone, or a child pulled out of school.

That shared precarity, between farmer and herder, is rarely acknowledged in how the conflict is portrayed. Most reports focus on violence: killings, raids, destruction. But the real story often begins earlier, with broken systems, shrinking trust, and a quiet dread that builds over time.

Nguru-Hadejia wetlands in Yobe, a once critical water source for herders, have become a point of contention as water access shrinks and farmlands expand. In Bauchi’s western agricultural belt, areas like Toro and the Yankari-Katagum corridor are now recognised zones of ecological tension, where water and land are in short supply.

Sanusi said there are no functioning mediation systems anymore. “In the past, we would call the village head. He would speak to both sides. Now, no one comes”

Some communities in Adamawa State have tried to fill that gap. Bello, a community elder, explained: “When animals stray into farmlands, we get reports from the police. First, we identify the culprit. Then, if he has been arrested, we ensure the farmer is compensated. We also discipline the herder to prevent a repeat.”

Experts note that local accountability matters. “In the North East, elders take action when community members rustle cattle. They report to the police. However, in places like the North Central, leaders often stay silent. That is what leads to retaliation,” Malik said.

In the absence of authority, vigilantes have emerged. Some protect farms. Others patrol bush paths. Most are poorly trained and loosely organised. Many are young men with long grievances and short tempers.

The result is tension that simmers without resolution.

Kamalu described his fear. “Maybe one cow enters. Then someone hurls an insult. Then they come back with weapons. Or maybe they don’t. But we don’t know.”

The fear is mutual. Herders move silently, hoping not to be seen, and farmers sleep lightly during the migration season. No one trusts the other or trusts the state to step in.

The deeper costs are not only in lost harvests or stolen cows, but in stalled futures. “Our children don’t get an education,” Bello said. “We don’t have healthcare. No water, no electricity. People stereotype us. It is all because of ignorance. If we were educated, we would have equal opportunities like others.”

Still, some herders are finding alternatives.

“We bought plots of land here in Jimeta,” Bello said. “That is our community now. Our children are in school. We created a ranch to keep our cattle during the dry season. After harvest, we buy stalks from farmers and feed them. Our cattle drink from the River Benue. We use boreholes from nearby communities for our water.”

They hope to buy more land. Build a dam. Dig a borehole. Secure a future.

For now, they adapt, one season at a time.

The security gap

What happens when movement is no longer managed, and survival turns into trespass? That question haunts the herders, who try to pass unseen, and the farmers, who try to protect what little they have. It also points to a more profound crisis that does not begin with herders and farmers but ends with them trapped in the middle of a larger security breakdown.

“The population will keep growing. People will need more land to farm and more space to live,” said Malik. “The government must evolve with these trends.”

The failure to adapt has opened the door for non-state actors. In some cases, herders say the attackers are not even Nigerians. Claims of foreign infiltration, fighters from Niger, Chad, or Mali crossing porous borders, are challenging to verify, but frequently repeated. The risk, Malik warns, is that armed groups now move across the region disguised as herders, exploiting migration routes that span West and Central Africa. Nigeria’s North East, the most significant entry point for cross-border pastoralists, is especially vulnerable.

Malik explained that even internal movement is no longer predictable. Routes once mediated by district heads and grazing committees are now insecure or unmarked. Communities that once welcomed herders have grown hostile. Vigilante groups have stepped in, blocking passage, collecting tolls, or enforcing rules with force.

“We encounter terrorists, especially in Borno,” said Bello. “They rustle our cattle or demand taxes. In 2017, over 100 of our cattle were stolen. Other herders lost more. Through our association, Pulako, we contributed to helping the affected herders, two or three cattle each. But it is part of why we left for Adamawa.”

In northeastern Nigeria, the Boko Haram factions of Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’adati wal-Jihad (JAS) and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) have embedded themselves in areas long abandoned by the state. Movement is no longer just a logistical challenge but a matter of territory and surveillance. Pastoralists must now navigate dry land, blocked paths, with armed groups asserting control.

“JAS rustles cattle and sells them in the south to fund their operations,” said Malik. “ISWAP taxes herders who graze in territories around Lake Chad. When JAS steals cattle from those herders, ISWAP intervenes to retrieve them. They even resolve herder-farmer conflicts, ensuring farmers are compensated when herds destroy crops.”

In the northwestern region, the dynamic is different. Terrorist groups have created informal taxation systems. “They extort herders, like JAS does,” Malik added. “When herders lose everything, they turn to kidnapping or robbery, or are hired by aggrieved herders to retaliate against farmers.”

We extensively documented this pattern across Nigeria’s conflict zones. In one report, Ahmad Salkida, Founder of HumAngle, who is an investigative journalist and one of the most authoritative voices on the Boko Haram insurgency, explained that herders under Boko Haram and ISWAP control are forced to pay taxes based on the size of their herd.

“They must relinquish a portion of their livestock,” he noted. “And due to multiple factions, they occasionally pay double, losing more than they can bargain for.”

In other parts of the region, herding communities are routinely forced to pay protection levies, coerced into supplying armed groups, or punished if they refuse, mirroring the same dynamics of extortion and control seen in the North East.

Mobility, once neutral and even protected, has become political. Herders, no longer shielded by the grazing route system, are exposed on every front.

There seems to be no national framework for managing trans-regional movement. Until July 2024, when the Nigerian government created the Federal Ministry of Livestock Development, no institution had the authority or tools to track who was moving, where, or why.

“Past governments tried to introduce ranching settlements,” Malik said. “The Buhari administration attempted, but the public saw it as a land-grab. The problem was poor communication. People have lost trust in the state, so they misinterpreted everything. However, the deeper issue is that each region has a different conflict. The North East is not the North West. So solutions must also be different.”

The state’s absence is not passive. It produces insecurity.

Farmers form vigilantes. Herders arm themselves. Encounters that once ended with negotiation now end in gunfire.

The National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP), introduced to prevent this scenario, has stalled, sidelined by politics and inconsistent implementation.

“It is a good idea,” Malik said. “If implemented properly, it could resolve many of these issues.”

With each unresolved clash, local trust erodes. With each unmapped corridor, non-state actors tighten their grip. And as the climate continues to dry rivers and strip pasture from the earth, pressure builds slowly, steadily, dangerously.

What must be done

If there is one thing everyone agrees on, it is this: what exists now is not working.

“The solution must begin at the community level,” said Malik. “We need to bring back the conflict resolution systems that once worked, those local processes that helped farmers and herders find common ground.”

However, informal peacebuilding alone would not resolve a structural crisis. The scale of Nigeria’s environmental collapse and mobility breakdown requires coordinated, strategic, and adequately resourced reform.

Malik believes ranching is essential to ending uncontrolled migration and giving herders security, dignity, and economic opportunity.

“Ranching is the most effective alternative. Moving cattle across states will always spark conflict,” he said. “But if ranches are developed properly, with clinics, water, schools, and markets, those are capital incentives. They make settlement viable.”

He insists this will require more than government goodwill.

“The private sector must be involved. Let investors lease land. Let herders produce meat and milk, and let the state earn revenue. With proper management, we wouldn’t need to import beef or dairy.”

Yet trust is fragile. Malik noted how the RUGA initiative failed not because the idea was flawed, but because people were not consulted. The controversial RUGA programme, suspended in 2019, stood for Rural Grazing Area.

“There was no proper engagement. The public saw it as a land grab. The government must learn to communicate. There must be transparency. There must be accountability,” Malik said.

He added that at the heart of the tension is something simple: survival.

“The farmer wants to plant in peace and feed his family,” he says. “The herder wants to graze and feed his cattle. When people are allowed to be heard, they often find solutions independently.”

Bello shares this vision, but with a local, seasonal approach.

“During the rainy season, the government should provide ranches for us to keep our cattle,” he said. “Farmers can let us graze on harvested fields in the dry season. Our cattle will help clear the land and leave dung for manure. Then, farmers can do irrigation farming on the ranches. If we rotate this way, both sides benefit, without conflict.”

Abdullahi agrees, but calls for sincerity: “If the government is honest about the RUGA settlement plan and implements it, this problem will go away. Also, forest rangers should treat us fairly. Don’t deny us access completely.”

From the farmers’ side, the expectations are equally modest.

“Herders should avoid people’s farms. Farmers should avoid blocking the grazing routes,” Sanusi said.

“The government should support us with fertilisers and pesticides, even if through subsidies,” Kamalu added.

The proposed NLTP is meant to address many of these issues. But it remains stalled, caught between politics and poor communication.

“If implemented well, it could solve most of the crisis,” Malik said.

Bello Ardo, a Fulbe herder, shares the challenges faced by nomadic herders in Nigeria as traditional grazing routes, known as burtali, have been erased by urbanization and farmland expansion.

The disappearance of these routes has led to increased conflict between herders and farmers as animals stray into cultivated lands, further exacerbated by environmental collapse and inadequate governmental support. Herders like Bello and Abdullahi are now facing disrupted migratory patterns, increasing resource scarcity, and the tension of armed conflict, pushing them to consider ranching as an alternative to traditional herding practices.

Experts suggest that resolving these conflicts requires a multifaceted approach, including reinstituting successful local conflict resolution systems, promoting ranching as a sustainable alternative, involving private sector investments, and ensuring government transparency. Implementation of the stalled National Livestock Transformation Plan could address some of the underlying issues, while both herders and farmers express a need for clear communication, fair access to resources, and mutual cooperation to avoid conflict. The urgency for a practical and inclusive framework is underscored by the growing insecurity and environmental pressures that threaten livelihoods and regional stability.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter