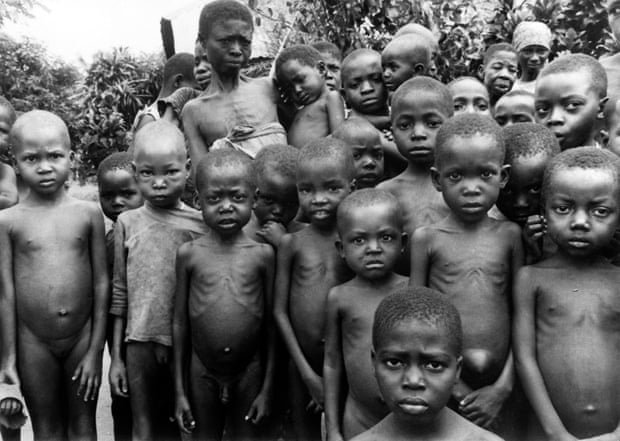

“Destructive shadow of bitterness, we’re shackled by the sins of our fathers”- Nigeria is haunted by the Biafran war

As the world marks the 53rd anniversary of the declaration of the Biafran state which was followed by the Nigerian Civil War, questions have risen as to why the country has failed to heal from the wounds and if any lesson has been learnt in that time.

A report by The World Peace Foundation which is affiliated with The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, USA says “the statistical data quoted for civilian deaths has ranged from a low of 500,000 to a high of 6 million. The ‘true’ estimate may never be known because there is no accurate baseline for comparison with both the 1962-1963 and 1973 suspect data.

“During the height of the crisis, the ICRC cited a number of 8,000 and 10,000 deaths per day. It obtained these figures based on random samples of death rates in villages, refugee camps and hospitals across Biafra, and argued that the estimates were likely to be conservative” the report said.

Despite the war ending 50 years ago, opinions remain divided on what lessons, if any, Nigeria has learned from the civil war. Some analysts have blamed the failure of successive leaders to dispassionately address the crimes committed during the war for most of the dysfunctionality in Nigeria.

The war started on June 6, 1067 and lasted till January 15, 1970. After the war, the ‘No Victor, No Vanquished,’ policy was put in place by Nigerian Head of State Yakubu Gowon, to reabsorb Biafrans, and many have argued that the policy alone, without concerted efforts to right the wrongs done has led to a near-collective amnesia of the civil war in the country as well as other crimes against humanity.

Speaking with NewsWireNGR, Cheta Nwanze, Lead Partner at SBM Intelligence, said one of the reasons Nigeria failed to learn from the war is because it made war criminals national heroes.

According to Nwanze, some of the key actors during the civil war have found their way into the Nigerian government and as a result the history of the civil war is being suppressed to “avoid staining their whites”.

“In many respects Nigeria is afraid of history.

“People who eventually became big in Nigeria’s government structure committed crimes that can only be described as war crimes during in the Biafra war. As a result, there was an interest in beautifying them and making them heroes rather than punishing them for their crimes.

“Essentially, there is a refusal to discuss history because many of these names have been passed into Nigerian folklore and they’re now mythical figures. So we have a situation where discussing history dispassionately will end up staying in their whites”.

He suggested that the failure of Nigeria to address the crimes from the civil war has gone on to normalise killings across the country for several years.

“The truth is that the ghost of Biafra is hunting Nigeria. Now we have a situation where because of that foundation of failing to punish people who have committed what are essentially war crimes, ‘It’s okay to commit mass atrocities and nothing will happen’.

“Since the Biafran war ended, we have had mass killings in Kajuru, Kano, Onitsha, Ugep, Kaduna, Ummuechem, Bakolori, Bauchi Zango Kataf, Udi, Jos, Yelwa, Shengdam, Maiduguri, Potiskum, Wudil, and many more.

“This creates a bitterness and something that essentially seeds more massacres to happen, and until Nigeria develops a culture of discussing what has happened dispassionately, we will not learn lessons” Cheta told NewsWireNGR.

Mr Alkasim Abdulkadir, who is the Head of Media and Communications at the National Commission for Refugees Migrants and Internally Displaced Persons (NCFRMI) noted that efforts were made to address some of the issues surrounding the war. He pointed out efforts at reconciliation and infrastructural development as commendable but agreed that “the hard conversations around why and what happened including alleged atrocities committed by both sides” has been largely ignored.

“Other countries that have suffered from extreme fratricide and Internal strife, crisis and civil war have had a memorial and national tribute. One of the most important aspects of this is the National conversation around closure.

“At the end of the Civil war we had national reconciliation processes like the Abandoned Properties Implementation Committee in the Eastern region in 1976. The Presidential Amnesty for Chief Ojukwu by the Shagari Government amongst several other measures at reintegration and reconciliation.

“However, all these precludes the hard conversations around why and what happened including alleged atrocities committed by both sides.

“It is important that perceived grievances are brought to the fore, discussed and implemented to address infrastructural deficits, human capital deficits and other indices of development.

“Personally, I am happy about the dredging of the River Niger, the building of the second Niger bridge, the international flights from Enugu Airport, the establishment of a port to serve the East and the critical appointments of individuals into key MDAs is a pointer to resting the ghost of the civil war. It is long deserved but slowly being achieved” Alkasim told NewsWireNGR on Saturday.

Alkasim’s cup-half-full view isn’t shared by the Country Director for the Open Society Initiative for Africa (OSIWA), Jude Ilo, who said it is likely that Nigerians are too ashamed to admit what they did to each other or afraid that addressing the wounds of the war could lead to many other wounds being opened.

“There has been a deliberate policy by successive Nigerian governments to suppress the history around the civil war and there could be many reasons for this.

“Perhaps as a country, we are too ashamed of what we did to ourselves that we want to forget, or we are too cowardly to face our reality and deal with it. It could also be that we are worried that we will open old wounds and create more problems.

“But the reality is that there is a wound that has not healed. It doesn’t matter how we cover it up and pretend that it is not there, it will continue to eat away at our essence as a country. And like any bad sore, it can only get worse if left untreated”.

Ilo argues that the refusal to address these issues will continue to keep Nigeria chained to the what he termed unresolved pain. “Without a shared narrative of the ugliness and pains of the war, our relationship with each other will always be chained to the reality of unresolved pain. We will always walk in the dark and destructive shadow of bitterness. Like slaves, we are shackled to the sins of our fathers” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter