Delta–Edo’s Deadly Highway: Between Kidnappers and Vigilantes

The Delta–Edo Federal Highway in South-South Nigeria is a vital artery for trade and travel. Lately, however, it has acquired a darker meaning: each trip along the Onitsha–Asaba–Benin–Lokoja axis has become a life-threatening gamble.

An invitation to a wedding ceremony in Lokoja set one traveller on a perilous road. He had been asked to represent the father of the bride, his maternal uncle, who was too ill to travel. The traditional rites had already been concluded in Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria, but the church ceremony in Lokoja in the North Central region required family presence.

The request came with both anticipation and dread. The irony was not lost on him: he had long resolved to write about the incessant kidnappings along the Delta–Abuja axis. Now, to fulfill a family duty, he would have to experience the very corridor of terror himself, the Onitsha–Asaba–Benin–Lokoja highway.

Before departing, he spoke with his editor at HumAngle, who agreed that the real story lay not in the ceremony but in the journey itself. And so, on a humid Thursday morning, he stood in Onitsha’s crowded motor park, a knot of anxiety tightening in his stomach. The destination board on the 14-seater bus read simply: ONITSHA — LOKOJA.

Inside the bus, anxiety was palpable, an atmosphere shared among strangers bound by a common fear.

Grace, a market woman travelling to Abuja for Omugwo—the traditional care of a daughter and newborn by the grandmother—admitted: “I prayed all night. My husband advised us to put our trust in God, yet my heart is pounding uncontrollably.”

Beside her sat Mr Osa, a civil servant returning to his post in Lokoja. He carefully noted the registration numbers of buses in their convoy, mentally mapping each checkpoint. “You can’t be careless,” he said, eyes sweeping the roadside forests. “They struck near Okene last week. Two buses. Nobody has heard from them since.”

Their driver, Ekene, a veteran of the highway, wore the calm mask of one long familiar with danger. Before departure, he offered a chilling briefing: “If we see anything suspicious, I will not stop. I will speed. Hold on tight. Do not shout. Everyone, please, pray.”

Mile by anxious mile

Crossing the River Niger into Delta State, the mood in the bus shifted, and conversation thinned. The lush vegetation became ominous, its density a perfect cloak for ambush.

Every slowdown was a small terror. Even police checkpoints offered little comfort as passengers wondered if the uniforms were real, as armed men have been known to mount illegal checkpoints as a disguise to launch attacks on unsuspecting motorists. Ekene would approach cautiously, rolling down his window just a crack, observing every gesture before halting fully.

Passengers became lookouts. A rustle in the bush could draw gasps from several commuters at once. Warnings and survival stories circulated not as casual talk but as grim caution. One woman recounted how her sister’s bus was stopped weeks earlier. “They took three people. The rest were left with a message: ‘Tell your people to pay fast, or we will kill them.’”

The question of who the kidnappers were surfaced, heavy with pain. “The ones who attacked my cousin’s bus spoke Fulani,” Mr Osa said. “When you’re in that bush and hear men with guns speaking, it’s hard not to profile. It is a poison they have introduced into our society.”

His words captured the tragic cycle: real violence feeding fear, and fear deepening ethnic suspicion.

Reaching Lokoja was like surfacing from underwater. The sight of the famous Confluence, where the River Niger and the River Benue merge into one, represented survival for them.

The wedding ceremony itself brimmed with joy and conviviality, but beneath the music and feasting, the shadow of the highway lingered. Everyone knew the return trip loomed just days away.

The return trip

Days later, they embarked on a return trip in a smaller Sienna bus carrying seven passengers. It was quieter but no less tense. The unknown haunted the journey out, but the return carried the weight of having already defied the odds once.

When the bus finally pulled into Onitsha Motor Park, the relief was physical. Shoulders slumped, smiles spread, hands clasped warmly. “Happy survival,” one passenger greeted. Another responded, “Same to you.”

They were no longer just co-travellers but survivors of a shared ordeal.

The story of this bus mirrors thousands of others. It echoes the trauma of drivers like Emmanuel Okafor, who says he prays constantly behind the wheel; of families drained by ransom demands; and of vigilantes rising in Delta and Edo in response to the vacuum of protection.

The experience also reveals how trauma fuels ethnic profiling and social fracture that linger long after the ambushes. It is within this fragile context that vigilante groups now operate, their presence offering both reassurance and new risks.

Emmanuel Okafor, 42, has plied these roads for 15 years. His faded blue minibus, scarred by countless journeys, is both his livelihood and his constant risk.

“Before, we worried about bad roads and breakdowns,” he said. “Now, I pray constantly, not just for accidents but for the men who come out of the bush with AK-47s.”

Drivers, he explained, have built informal survival strategies: headlight signals, coded radio messages, and alternative routes. But kidnappers adapt too, posing as stranded motorists or manning fake checkpoints. “We are always adapting,” he said grimly. “But so are they.”

Delta’s crackdown: Technology turns the tide

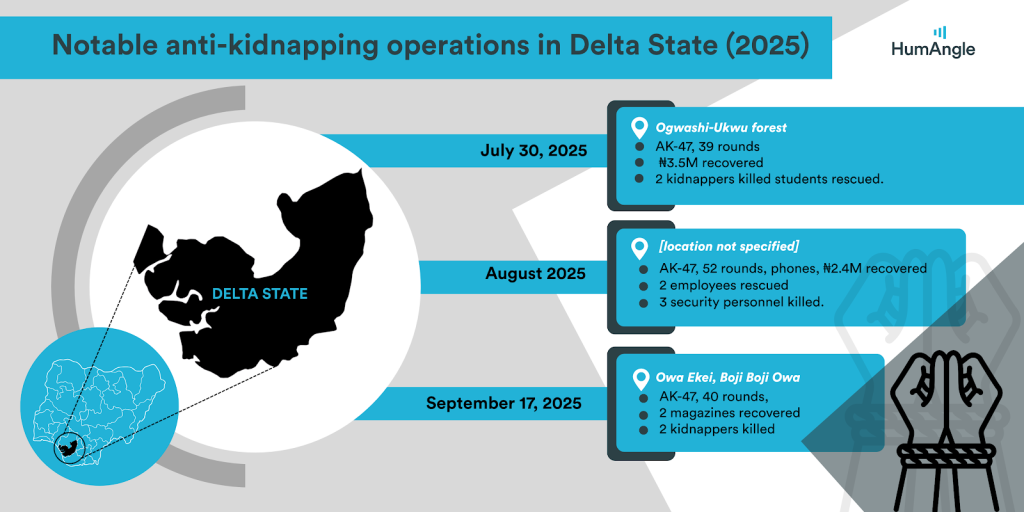

In response, Delta State has launched a “data-driven, technology-enhanced anti-kidnapping strategy.” On July 30, security forces stormed a kidnapper’s camp in Ogwashi-Ukwu forest, recovering weapons, ammunition, and cash proceeds from ransom. The operation resulted in the rescue of several students.

Officials say kidnappings have reduced. Residents cautiously agree, though some note that pressure in Delta has displaced gangs into Edo State, shifting the danger rather than eliminating it.

As kidnappers regroup in Edo, the violence worsens. A local politician in Akoko-Edo has remained in captivity for over 140 days despite ransom payments. Two seminarians abducted in July were forced on video to hold a human skull while ransom demands were made.

The toll is economic as much as personal. Farmers abandon their fields, traders steer clear of roads, and even major companies operating in the region face deadly consequences for their workers and security guards.

The vigilante response

Vigilante groups have proliferated both states. Some communities credit them with reducing street crime, while others recount abuses and killings. Across Nigeria, vigilantes have been implicated in at least 68 deaths within three months.

Commander Jude Ikpoaku, of the Delta State Vigilante Group in Asaba, defended his men as citizens first, protectors second. “We know our communities,” he said. “That is why we can protect them where formal security struggles.”

Still, he admitted challenges: not everyone with a stick is a vigilante, and without a statutory framework, abuses are possible. Critics caution that in the absence of regulation, these groups run the risk of exacerbating the crisis they aim to resolve.

Governors and state assemblies have pressed for more patrols, better use of security vehicles, and the deployment of thermal drones capable of detecting human presence under thick forests. Security agencies stress the importance of citizen intelligence, urging communities to share information.

But inconsistency remains. Military checkpoints appear and vanish. Road conditions remain dire, often forcing vehicles into vulnerable slowdowns—perfect opportunities for ambush.

Beneath the policy debates lie deeply human costs—families shattered by ransom demands, drivers living in constant fear, and communities fraying under suspicion. Yet resilience persists. Communities are organising, neighbours watching out for one another, and ordinary people are finding extraordinary courage.

As Commander Jude reminded, “This is our home. These are our people. We have nowhere else to go. So we will stand, we will fight, and we will take back our communities—no matter how long it takes.”

For now, the Delta–Edo highway remains a nightmare. Every trip is a test of faith. Every safe arrival is, in itself, a survival story.

A traveller was assigned to attend a wedding in Lokoja and had to navigate the perilous Delta–Abuja road, notorious for kidnappings. This journey highlighted the shared anxiety among passengers, who leaned on prayer and vigilance for safety as checkpoints offered no real comfort. The return trip was equally tense but ended in relief upon arrival, underscoring a tale of endurance shared by many on this dangerous route.

Delta State's anti-kidnapping initiatives, incorporating technology, have shown some success in reducing crime, yet displaced gangs have migrated to Edo State, continuing the threat. In response, vigilante groups have emerged to fill security gaps, sparking debates over their methods and potential abuses. Despite this, communities remain resilient, led by figures like Delta State's Jude Ikpoaku, committed to reclaiming safety through coordinated efforts and improved intelligence sharing amidst ongoing challenges and distrust in formal security measures.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter