#DapchiAbduction: Because They Went To School, They Paid With Their Lives

On this day in March 2018, ISWAP terrorists brought back over 100 schoolgirls they had whisked away from their dormitories in Dapchi, northeastern Nigeria. There were some who did not make it back alive. We spoke to their families.

Alhaji Hassan looks like he could break into tears any moment. Not the kind of weeping that might hint at an intense wave of sadness, perhaps, but the kind that could express his inability to comprehend the injustice he has had to endure.

He moves his hands erratically to gesticulate as he talks. It is evident that the movements are made subconsciously; he is merely consumed by a blend of rage and pain that his plump body does not seem able to contain. Because four years after the horrifying Boko Haram abduction that killed his 14-year-old daughter, he is sitting beside this reporter and speaking for the first time about the circumstances surrounding her death.

“I have never even spoken of it,” he says, his voice thickened by bitterness. “Not even with my brothers who were with me on that day. You can ask them.”

His brothers, sitting with him, nod in agreement.

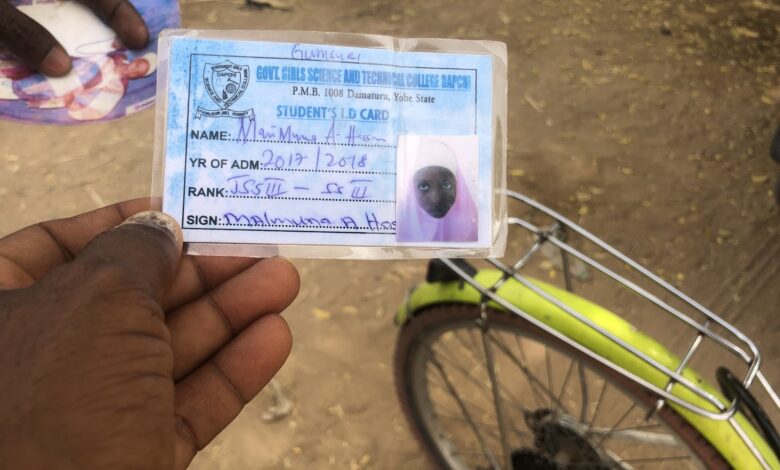

Hassan suspected that his daughter, Maimuna A. Hassan, had died, long before the news came. The news had spread that five of the 115 Dapchi girls had died shortly after their abduction and while being conveyed to the forests where they would be kept, but there had been no mention of their identities. Still, he suspected that she might be one of them.

As he speaks, he is surrounded by friends and brothers, including Alhaji Adamu, another father similarly bereaved. Alhaji Adamu sits quietly during the first few minutes of the conversation. But at some point, he begins to vent out his grief, too.

The Dapchi girls had been in the habit of fasting on Mondays and Thursdays, as are many Muslims. They were abducted on a Monday, and so they had been fasting. They had not had the chance to break their fast when the attack occurred. In addition to the lack of food and extreme thirst, they also trampled on each other and painfully congested the truck brought by the terrorists. These conditions led to the deterioration of the girls’ health.

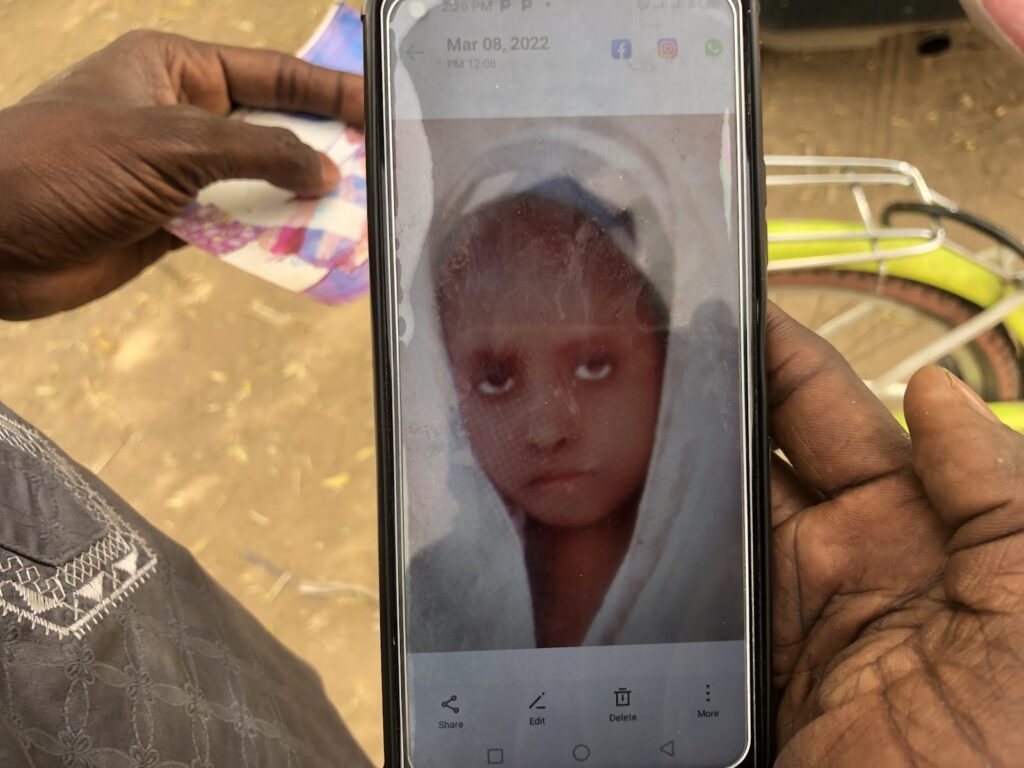

There was also the trauma of the experience, which Alhaji Adamu believes was the principal cause of his daughter’s death.

“See, when Aisha was still alive, whenever she did something bad, and I threatened to punish her, she would be filled with so much fear that she would not even sleep at home. She would run away to her aunty’s house. Imagine that kind of person being subjected to all that trauma? The gunshots and the stampede? I knew she would not be able to survive it.”

School abductions

On the night of April 14, 2014, militants of the Boko Haram terror group arrived at Government Girls Secondary School, Chibok, in Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, in several trucks, wielding dangerous weapons.

That night, they made away with 276 girls who had been students at the school, and who were mostly aged 16-18.

It was an attack that threw the Nigerian populace and even the international community into wide outrage and mourning, creating activists out of citizens who would later coin the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls, demanding that the government secure the release of the girls.

Eight years later, not only would over 100 of the girls still be unaccounted for, but Nigeria would also have witnessed countless more similar attacks and abduction of children from schools, including what would later be known as the Dapchi abduction. The abduction took Aisha Adamu and Maimuna A. Hassan’s lives.

A 2018 UNICEF report estimates that the terror group has abducted over 1,000 children since the beginning of the insurgency. According to the group’s representative in Nigeria, Mohammed Malick Fall, “children in northeastern Nigeria continue to come under attack at a shocking scale … They are consistently targeted and exposed to brutal violence in their homes, schools and public places.”

The Dapchi abduction

At 12:39 p.m. on Feb. 19, 2018, Alhaji Adamu’s phone rang with news that would change life as he knew it.

It was a distress call from a nearby town, and the man on the other end of the phone line was telling him that Boko Haram terrorists had been sighted in several trucks and were rumoured to be on their way to the Government Girls Science and Technical College, Dapchi, where his daughter was a boarding school student. He and his family were not residents of Dapchi. They lived in Jumbam, a town just five kilometres away.

There had never been an abduction like that in Dapchi before. In fact, the small town, 100 km away from the state capital, Damaturu, had been relatively safe even in those days of unending attacks in neighbouring Borno. But Alhaji Adamu knew about the Chibok abduction, as did everyone else, and so he was aware of the possible implications of that news.

“That phone call came in at exactly 12:39 p.m.,” he says.

He knows because he had written it down in his jotter in his attempts at memorialising every detail about his daughter’s death.

The caller was informing him that the terrorists had passed a town called Gumsa and were presumably headed to the school in Dapchi.

About an hour later, he received another call that said they had been sighted again. It was then that Alhaji Adamu called the local government chairman at Dapchi to enquire if any security measures were being taken to ward off the impending yet seemingly preventable attack.

“I called him and told him. I said they are saying these people are drawing nearer to Dapchi fa, and he said he knew, that wallahi he had heard the news too, and that he had called the commander in Geidam and informed him as well. Ten minutes later, I called him again. I said people are saying these people have passed Galimbo. He said, again, that he had informed the commander.”

At a few minutes past 5 p.m. that day, the dreaded news reached Alhaji Adamu: the militants had entered Dapchi.

“Before 6 p.m., they had abducted these children and loaded them onto their trucks like livestock. Our children were wailing and we could hear them from the distance because they passed through the back of this town. We heard them as they were wailing. Yet, the government tried to deny, at some point, that the abduction ever happened. Because we are nobodies. Because it is not their children that were abducted,” he says, his voice rising, breaking.

What Adamu finds most unforgivable after the abduction, he says, is that when he and other parents went to the school the day after, seeking to know what exactly had happened and how it had happened, and what measures were being taken to procure the release of their children, they were brutalised by security forces who had now been stationed at the gates.

“Because we dared to ask after our children. They didn’t even let us enter the school premises. They insulted us and beat us up. They dehumanised us. They made us sit on the bare ground. All because we were asking for our own children. Our own children fa.” The memory seems unbelievable even to him.

He recalls that despite their frantic attempts at warding off the attack by getting the attention of the authorities when they first heard that the militants were on their way, security forces did not arrive at the scene until around 8 p.m. that day.

There are accounts that though the town and the road to it had been immersed in heavy military presence during the preceding month, the military had left merely hours before the attack occurred. However, residents of Jumbam tell HumAngle that the military withdrawal had occurred a week before.

Security analysts say there are exceptional circumstances where troops may be ordered to retreat before an attack, especially where the personnel on the ground are likely to be overpowered by the coming threat. Anything to the contrary would seem a suicide mission that would not benefit the state nor the victims.

Governor of the state at the time, Ibrahim Geidam, had blamed the attack on the military, saying that they had withdrawn their troops without informing state authorities. The Nigerian Army, however, said the officers were only redeployed to the Kanama following attacks on military bases along the border with the Niger Republic. “This is on the premise that Dapchi has been relatively calm and peaceful, and the security of Dapchi was formally handed over to the Nigeria Police Division located in the town,” said Onyeama Nwachukwu, then Deputy Director, Army Public Relations.

During the entire month of the children’s captivity, Alhaji Adamu and Alhaji Hassan recall attending several meetings within themselves, making several trips to the school, and existing in a constant state of dread and uncertainty about their children.

“Today we would hear that they will release them tomorrow. Tomorrow, we will hear that it’s now next tomorrow.”

The release of the Dapchi girls

Finally, on Wednesday, March 21, 2018, while Alhaji Adamu was away in Damaturu, the Dapchi local government chairman whom he had frantically called on the day of the attack, phoned him to say the children were on their way back, escorted by the terrorists themselves.

“He called me and said news just reached him that the girls were on their way back, that one girl had already even been dropped at home in her town, Gumsa. And that we should hurry to the school in Dapchi to receive them.”

Adamu drove like a madman down to Dapchi. He made it there in time to see the terrorists offloading the children from their trucks. He watched as they posed with the children and held dangerous weapons to scare off onlookers. And then they left, as dreadfully as they had come.

It was from there, as he looked into the crowd of girls searching frantically for Aisha yet not seeing her, that he knew for sure that she had died. Her friends would later confirm it to him.

He recalls that government officials swooped in immediately and began to mobilise the children for photos, and for onward transportation to Nigeria’s capital city, Abuja, to meet with the presidency.

“They wouldn’t even let parents interact with their own children at the time,” he remembers. “They kept yelling at us to move back, and asking: did we know what it took for them to secure the release of the girls? Girls that we saw being delivered by the terrorists themselves.”

Alhaji Hassan, on the other hand, arrived home from a nearby village to news of the children having returned. He remembers entering his compound, now swamped with people he would later realise were mourners, he remembers them averting their gaze from him whenever he tried to meet their eyes, he remembers seeing his wife, flanked by her friends, weeping uncontrollably. And he remembers knowing then, without question, that his Maimuna was one of the five who did not make it back alive.

“I wanted someone to attempt to talk to me, so that perhaps I may get to cry,” he admits. “I wanted something to happen to cause me physical pain, I just badly wanted an outlet for the intense grief that was consuming me at that moment. But Allah did not will it to happen,” he says.

One of his brothers begins to weep silently.

But Maimuna did not die alone. She died holding on to her sister’s hand.

“I held on to her hand and she held on to mine. I was stronger because I was not fasting. She was fasting. She had even performed ablution to pray and I had set her dinner for her to break her fast with, in the dormitory. We were just waiting for the call to prayer so that she could eat, when the attack happened. Even when they were loading us onto the truck, we were holding hands.”

Maimuna, trampled underneath other girls, continuously cried out for water. Her sister echoed her cries in the hopes that their abductors might have mercy and extend water to them, she says. But it was not to be. Maimuna died shortly before they reached Gumsa town. All the girls who had died, died before Gumsa. It was then that the terrorists parked, dug a hole by the road, rolled the dead bodies into it, and buried them.

“There was no proper burial for them,” she stresses.

Then, they were grouped into clusters and split to other trucks, to give room for ventilation. They were also given water.

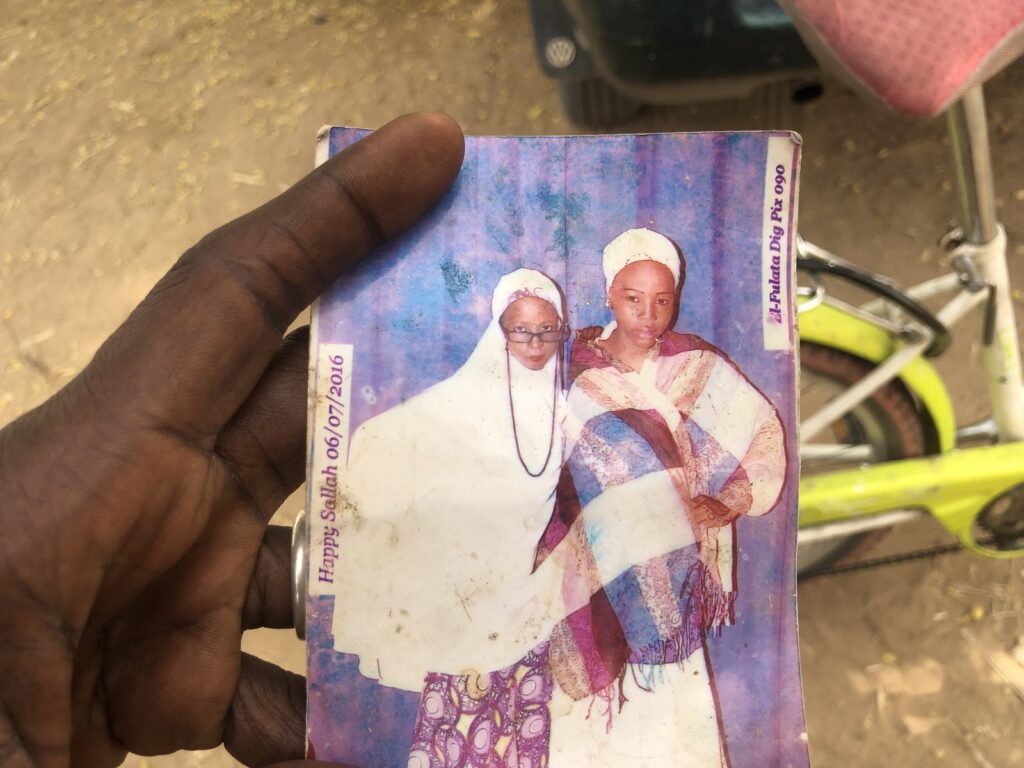

“Maimuna was very sweet. She laughed a lot. She loved people and people loved her too,” her mother tells HumAngle.

“She was so popular. In fact, after they were abducted, this entire village grieved her abduction in a manner that you would think she was the only one that had been abducted.”

“We have been deeply wounded by these people,” she says of the terrorists.

She recalls seeing the joy on the faces of other parents whose children had returned safely. She recalls looking into the crowd, searching for Maimuna. And she recalls the creeping thought taking root in her that perhaps her own child did not make it back alive.

“We were so overjoyed when we learned that the girls had been released. We thought it was all of them that made it back but I did not see my own child. I went everywhere in that crowd, I searched everywhere, I did not see my child. And finally, I asked: where is my Maimuna? And that was when they told me. I fainted immediately.”

She still spends time looking at her pictures and holding tightly to her clothes.

“Maimuna did not even like to go to school. I was the one who had to force her to go. I begged her and convinced her until she agreed. We first took her to a school in Damaturu, then we moved her to the school in Dapchi.”

There is a sense of heavy regret in the woman’s voice.

Reparations

In addition to witnessing the joys of parents whose children returned, Maimuna’s mother also witnessed agencies and even the government sometimes sharing relief materials to them in those early days.

She has never once received as little as a condolence message from any state official, she says. Her deep loss has gone unacknowledged, with neither justice nor reparation.

Alhaji Adamu holds the same grievance. He says nobody had ever come to condole with them from the government, nor made efforts to know whether they were still sending their children to school.

After the abduction, the school was moved to a safer place in another town, Nguru, but no efforts were made to see to the successful transfer of the students, residents say. The only organisation that has given the kind of support that Alhaji Adamu had hoped to get from the government, he says, is the Murtala Muhammad Foundation, which has taken sponsorship of his other daughter’s education.

“They also call from time to time to check on her progress. They have undertaken that they will sponsor her education right up to the university if she chooses to go that far. We talk about the foundation all the time because we are very grateful to them. And it is not just my family they have provided support for. There are other houses too,” he says.

“It’s what the government should be doing. Let us just know that our children did not die for nothing. Let us know that we matter.”

For many Nigerians, justice entails getting the children released, and so after the release, there was no talk of reparations nor restitution for them and their families, for the horrors they have had to endure. For the Nigerian state, their release is reward enough. And so those who died, remain forgotten. But not to their families.

This report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter