Globally, the outbreak of COVID-19 was a defining moment. Governments, individuals and institutions have had to find and adapt to new ways of living. It was one unexpected experience, yet the world had to find a way around it and move on.

Like many other human endeavours, journalism experienced one of its most trying and dramatic moments with the outbreak.

There has never been a time that many professions – journalism inclusive – have come under such a threat, putting practitioners on edge. Many jobs were lost, and a lot is still being lost. Many newsrooms are currently struggling to continue as finances dwindle.

“Newsrooms worldwide are under intense financial, physical and psychological pressure during this pandemic,” said Emily Bell, Founding Director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, in a report.

There is no denying that the pandemic has transformed the daily business of news gathering and publishing.

News-gathering during the pandemic, journalists’ experience

News-gathering and reporting under the pandemic are as difficult as reporting the pandemic itself, which the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) says is arguably one of the most important and complex stories of our time.

As nations were forced to impose lockdown to contain the spread of the virus, journalists could not afford to move around, even when there were issues to cover, deadlines to meet, and new grounds to break. Reporting under COVID-19, according to Onyedinefu Godsgift, a Nigerian journalist with Business Day newspaper, was tedious.

“Reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic was initially tedious for me because everything went virtual,” says Gift, whose daily beats include reporting on health. “I was used to the physical reporting method, so adapting was initially difficult.”

Many journalists across newsrooms agree there has been no time they have been on edge in the course of discharging their duties than in the months following the outbreak of COVID-19. News-gathering and reporting and the need to protect themselves were critical and competing needs.

“There were difficulties accessing sources for interviews face-to-face because some wouldn’t want close contact with reporters”, laments Chukwu Chidinma, a journalist with an online newspaper, Platinum Times.

“Ministries, departments and government agencies now invite just a few persons for briefings/events to adhere to social distance principles,” she adds.

With the new realities, newsrooms, event organisers and newsmakers evolved new approaches to organising events, including press conferences. Technologies intervened. Virtual meetings became vogue. Telephone interviews, calls on Skype, Zoom, and Google Meet became the new world order for journalists and, of course, governments and the private sector.

“Most events are now virtual,” Chidinma says, before quipping: “You must have money for data to sign in. So it is cost-consuming.”

The COVID-19 pandemic comes with a barrage of challenges for journalists across Africa, says Abiodun Jamiu, a student reporter. As a greenhorn in the business of reporting, he describes the health crisis as overwhelming.

“As a student journalist, I was not exempted. It was overwhelming, especially due to an inadequate support system for journalists of my ilks,” Jamiu says.

“Apart from working remotely, which comes with its ordeal, especially for those that could hardly work without supervision, there was no personal protective equipment which constantly exposed me to risk of contracting the virus.”

Impediment to reporters travelling

The lockdown and movement restriction impeded journalists’ access to sources for their reports, and investigative journalists were more affected.

“Personally, it was challenging for me because the restriction in movement limited my movement in gathering sources for my stories, considering I travel mostly out of my area of residence to meet sources for my stories,” says Amos Abba, an investigative journalist at the International Centre for Investigative Reporting.

“This affected my input as an investigative reporter because I had to resort to more feature stories and analysis reports in a bid to keep my writing quota on my beat.”

Jamiu, who is also into investigative reporting, corroborates this. At the peak of the pandemic, when government ministries and departments were closed as part of the measures to contain the spread of the virus, journalists complain they had difficulty getting other angles to balance their reports.

“As a U-monitor with PTICJ, which required that I visited these ministries to access information, getting information to balance my reports was a journey from heaven to hell as most of them hardly responded to letters sent to their ministries, citing COVID-19 restrictions. And when they replied, it would be too late for the report,” the young journalist recalls.

But all was not gloomy for the profession and practitioners as, according to Abah, the pandemic has also changed the face of digital journalism.

“It made me more critical about presenting data in useful and relevant ways that audiences can connect to more easily.”

“My approach to investigative reporting at the height of the COVID-19 restriction involved sifting publicly available government records to track down government spending on COVID-19,” he says.

This also comes with its challenges too, though temporary, says Godsgift. “I was not conversant with these virtual platforms. I experienced several hitches like poor network, power supply, and not to mention the high data needs.”

Generating contents in a pandemic

The pandemic led to a decline in filing daily news, especially as it limited reportage to health, education and economic issues. But journalists have since adapted to the new realities.

Christain Baars, a journalist with NDR, a state-owned radio in Hamburg, Germany, says he has been working “almost exclusively from home for a year now.”

“The positive thing is that many things are now possible that were previously considered difficult. For example, many press conferences or background discussions now take place online via video conferences.”

“That makes it possible for us to follow all this flexibly,” says Oda Lambrecht, who works with the television station of the NDR. Like many others in Nigeria and across the globe, they can now conduct interviews for radio and television almost exclusively via video calls at the moment.

“The technical quality is not very good, but acceptable. Sometimes you even save time and money because you don’t have to travel,” Baars notes.

The duo, however, laments that the direct contact with colleagues and the personal conversations with other people, which journalists otherwise often had during events or, for example, before and after interviews, is, of course, missing. “And that is, of course, a very important factor,” Lambrecht says.

Angela Atabo, a reporter with the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN), believes that the COVID-19 pandemic shook the foundation of everything in the world and the various sectors of the economy. The media sector is not left out; she observes.

“For instance, before the pandemic, I was covering daily news events almost every day, but during the lockdown, such events were shut down and even after the lockdown was eased, most organisations could not continue with the events,” Atabo says.

But she says the pandemic has led to the increased publication of special reports, features, opinion writings and community reports.

“Nevertheless, the pandemic brought some positive technological changes to the media space; for instance, it fostered the use of social media in reportage and news coverage as many organisations took to social media like Skype meetings, Zoom, Microsoft Teams, among others to hold meetings,” she concludes.

Godsgift believes the pandemic has, in the end, made the work easier for journalists. She remarks that the lesson learnt is that the world is going digital and “we reporters have to adapt.”

Difficulty in funding

Many newsrooms struggled to stay afloat as revenue dropped due to the economic meltdown occasioned by the pandemic.

The pandemic further led to the loss of jobs for a lot of private-sector media practitioners because of the decline in stories and advertisement, which crippled income. Newspapers print runs were reduced, pages slashed, salaries cut, and workers were told to go.

It has been such a precarious situation for the media industry as it is for other sectors.

By the turn of 2020, major media outfits in Nigeria such as The Punch Newspaper, The Nation, Daily Trust and AIM group (owners of Nigeria Info., Cool FM, Wazobia, and Arewa) had implemented one policy or the other that led to the loss of jobs for their staff or conversion from permanent staff to freelancers.

Non-profit newsrooms whose operations are supported by funders are also experiencing dwindling funding as the pandemic continues. Funders are reviewing their spending globally, affecting their beneficiaries due to the economic recession that the COVID-19 unleashed on the world.

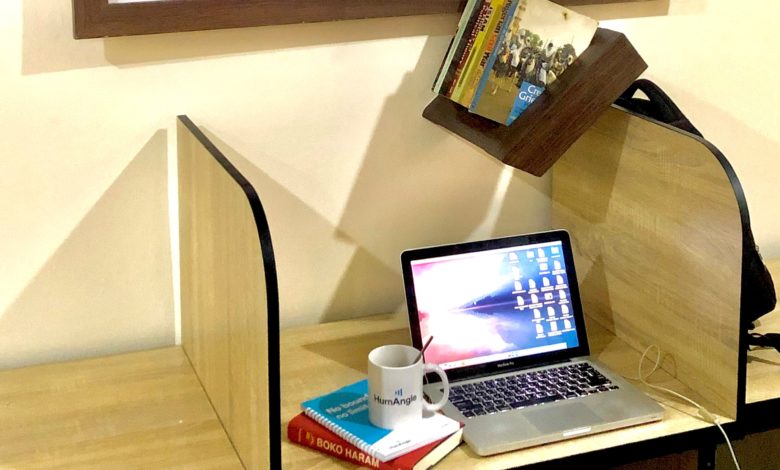

The HumAngle experience

HumAngle was just born when the pandemic struck. The impacts are better imagined than experienced, but we survived the shocks, despite the vulnerability of being a newcomer.

The journey was bumpy and smooth. And looking back after one year as a newsroom working amidst a debilitating pandemic that threatens human existence, and succeeding at the same time means a lot to us.

Everything came under threat − newsgathering, reporting, physical meeting in the office and of course funding − and against all odds, we are, one year after, moving on with the ‘new normal’.

The credit goes to the editorial team that rose to the occasion when newsgathering and reporting seemed impossible.

Like many newsrooms across the world, we resorted to remote work − the safety of our reporters was necessary as much as our desire to be the first in conflict-reporting in Nigeria and indeed in Africa.

Continue reading…

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter