Could The Dangwal Put An End To Nigeria’s Farmer-Herder Clashes?

An old pastoralist custom of placing a curse on lawbreakers is, to an extent, still respected today. Residents of Guri in northwestern Nigeria checked if it would end over a decade of violence.

In April 2022, residents of Guri gathered in the Model Boarding Primary School premises to witness a ceremony they hoped would restore peace to the area. The community leaders had arranged for a Dangwal-Pulako ritual to mend relations between the local herders and farmers.

This happened about two weeks after a clash erupted between the two groups in the Guri market of Jigawa State, Northwest Nigeria. The clash was brutal and the market square was filled with blood and cries of pain as the herders and farmers fought fiercely. In the end, the market was left in shambles and five herders lay dead on the ground, with many others injured.

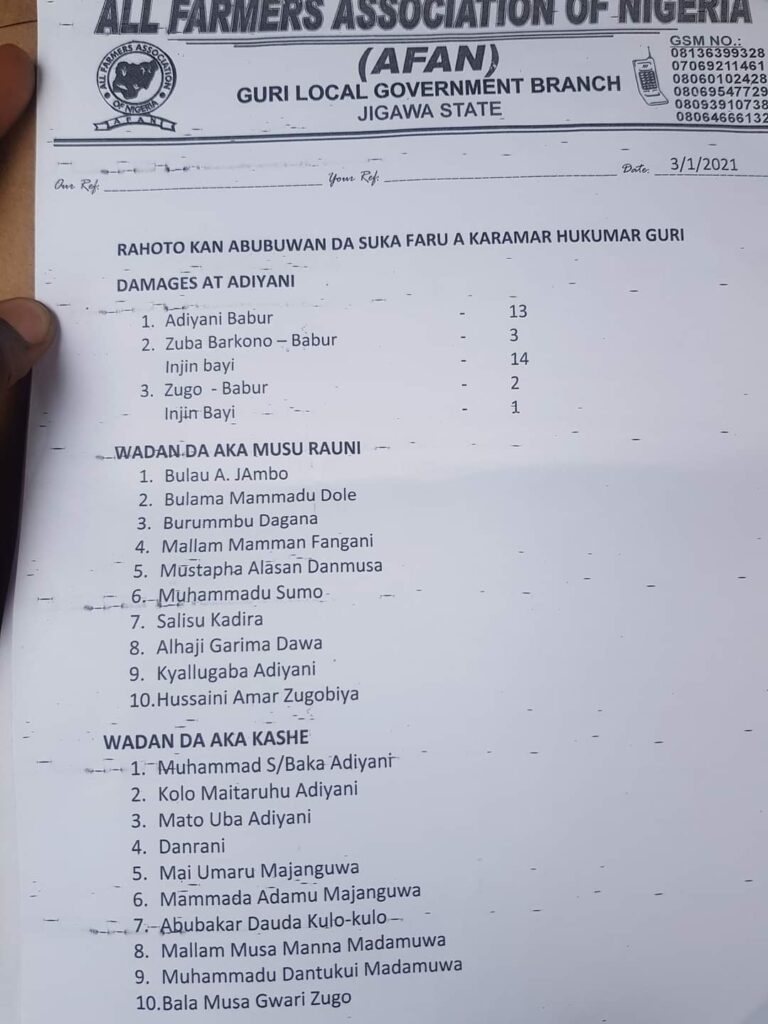

The clash itself erupted after two people were killed in Guri in March 2022 as a result of a fight between crop farmers and cattle herders. A situation report by the All Farmers Association of Nigeria said some herders had moved onto a crop farmer’s land and killed him with a bow and arrow.

Farmers, who make up most of the population of Guri, fought back by randomly attacking herders at the weekly market. “Farmer-herder clashes have been worrying Guri for more than a decade,” said Baballo Mato, chairman of Muryar Jama’ar Guri (literally, The Voice of Guri People). According to him, several efforts aimed at solving the situation were unsuccessful.

And then the idea of Dangwal came.

Dangwal is meant as a traditional and spiritual approach to peacebuilding and restoring the brotherhood between farmers and herders.

The ritual involves placing a curse on anyone who tries to start a fight or break a community rule. It is an integral part of the pastoralist culture.

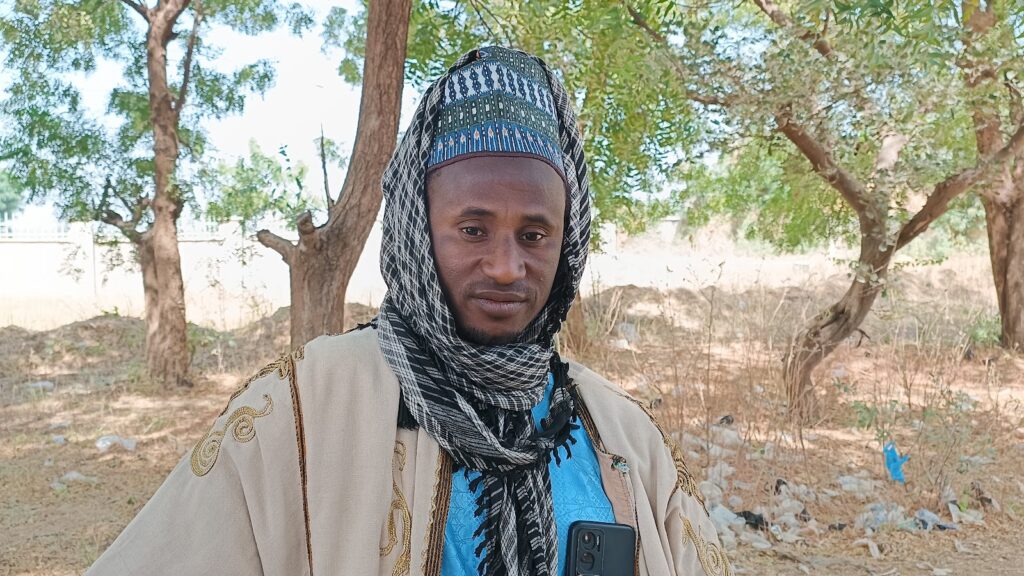

“[They] respect the tradition and believe that if anyone breaks the Dangwal, his animals and other property will be cursed,” said Ado Musa Bodala, secretary of Miyetti Allah (association of cattle breeders) in Guri, who helped make the process happen.

The ritual was a grand occasion, with community leaders and police present to witness it. The atmosphere was tense as Bodala stood at the centre of a circle formed by the participants; beside him was a symbolic leaf and a pack of kola nuts to be distributed to communities to indicate that the ritual had been held.

As the ritual began, Bodala stood, his voice resonating through the crowd. He warned that anyone who dared to incite violence between the farmers and herders would face the wrath of Dangwal. The people listened attentively, knowing the gravity of the ritual and the importance of maintaining peace.

“Anybody who destroys farms, kills an animal, or engages in any form of illegal transaction through buying or transporting stolen items will be cursed by Dangwal,” Bodala said, repeating to HumAngle what he had told the crowd.

Bodala then turned to the farmers and reminded them that all of them were Muslims. He said they were also seeking intercession through the Holy Qur’an for God to curse anyone, whether a farmer or a herder, who violates the peace pact.

“This was done so that anybody who may say he doesn’t believe in the Dangwal will fear the Qur’an and do the right thing,” Abdullahi Gaji, the Murshid of Tijjaniyya Sufi Order and an Imam in Guri who was present during the Dangwal, told HumAngle.

Gaji remembered it was the Chief Imam who took the Qur’an to the event and made the prohibited activities clear: robbery, buying stolen goods, destroying farms, and so on.

As the ritual came to an end, the community leader declared that peace would be maintained and that anyone who dared to break it would face the curse of Dangwal and the Qur’an. The ceremony ended on a peaceful note, and the people dispersed, leaving the powerful energy of the ritual still lingering in the air.

“We’ve had some days of peace,” Mato remembered. “Crimes dropped and activities continued peacefully.”

But then, a few months later, the problems returned.

Just a few metres from the road connecting his farm to the herders’ hamlets, Garba Muhammad was intercepted by two lanky men he suspected were herders, one wearing a mask and the other wielding a knife and stick.

The incident happened one afternoon in Oct. 2022 as Muhammad returned from his farm.

His initial instinct was to run for his life, but he quickly realised this could prove a fatal mistake. Running away wouldn’t protect him from the attackers’ arrows. He, therefore, made the decision to stop.

They immediately demanded that he take off his shirt and hand over his possessions. Muhammad refused to comply because he was afraid that if he did so, they might pounce on him and kidnap him. But his refusal led to a severe beating.

He was unable to defend himself and started screaming to attract passers-by.

“They tried to stab me, but the blade didn’t penetrate, so they used a large stone to bring me down,” he told HumAngle as he sat next to his hospital bed, receiving care for his injuries.

Fortunately, someone heard him screaming and intervened. But both the victim and his helper were not prepared enough for the violence. So, the rescuer also became a victim. Then, suddenly, as if suspecting there could be more people around to intervene, the assaulters ran off.

Muhammad’s story spread, prompting many farmers to prepare for the worst. More attacks have since been recorded.

In Jan. 2023, Alhaji Pullo was on his farm with his boys when he and herders passing through his property got into an argument. The misunderstanding escalated into a full-blown fight that led to him being stabbed in different parts of his body and having one of his hands amputated.

“He is currently in the hospital in Guru, Yobe State, receiving medications,” Mato said.

They used to live in peace

Farmers and herders in Guri used to live peacefully. They were neighbours, and over time, they formed close relationships with one another. They would often intermarry, and their children would grow up together as friends.

But as time passed, the population grew and land became scarce. The farmers and herders competed for resources and tensions began to rise. The farmers wanted to expand their fields, but the herders wanted to keep their grazing land.

“Farming land is not sold in Guri. The local authorities provide land to anybody who comes and says he will engage in farming activities, especially companies and security men,” Bodala told HumAngle. “Occasionally, a government official transferred here to work would ask for a farm to start farming. He typically receives a grazing route that has served as an animal passage for years.”

According to Abdullahi Guri, a young resident, most killings in Jigawa occur along the routes cattle herders use to transport their animals to neighbouring states and countries like Chad and Cameroon. They are usually blamed on “strange herders.”

He said there hasn’t been a year in the last decade without reports of killings along at least one of these routes. “That violence resulted in farmers and herders in Guri frequently fighting each other.”

Other local government areas in Jigawa with a similar situation include Hadejia, Kirikassama, Kafin Hausa, Birniwa, Auyo, Ringima, Miga, Sule Tankarkar, Babura, Maigatari, Birnin Kudu, Kiyawa, and Gwaram.

On these routes, herders frequently engage in violent clashes with farmers during the harvest season as they get ready to move from northern to southern Nigeria and, in some cases, Cameroon. This also occurs when they return to northern Nigeria during the rainy season.

Studies show that the government and farmers’ encroachment on grazing reserves and stock routes, population growth, climate change, and the spread of deserts made things worse between farmers and herders in Jigawa. All these factors combine to make solving the issue a herculean task.

In 2021, ten residents of Guri were killed and another ten injured in an attack that was attributed to herders. That led to a counterattack which saw numerous buildings razed. Before that, two Guri farmers from the village of Madamuwa were killed between September and October of the previous year.

Abdullahi, who is connected to the Fulani community in Guri but is also a local farmer, blamed recent attacks in Jigawa communities—including Guri—on herders who had fled conflicted areas of Zamfara. According to him, most people detained in the wake of the attacks were unfamiliar faces with no connection to the Fulani people who had lived nearby for years.

Why is Dangwal not effective?

2022 was not the first time Dangwal was done in Guri. In 2020, there was the implementation of Dangwal in the Kadira village by a group of locals who had grown tired of the ongoing hostilities in their towns and villages.

Even though the prescribed Dangwal rituals were followed, there was still some bloodshed, though on a small scale.

But why?

A security officer who spoke to HumAngle and requested anonymity said several factors blocked the full success of Dangwal in some areas of Guri.

He explained that the tradition is important to the older Fulani people, but the younger generation no longer respects it and does not perceive any reason to be afraid of the consequences of breaking it.

He explained that this occurs due to Fulani youths visiting various regions of the nation and returning with no regard for long-standing customs.

“Some of them are immersed in drug abuse in addition to having youths travel to the South and neighbouring nations like the Niger Republic.”

Some of these young people use drugs and commit crimes, not realising the seriousness of their actions until they are sober, he said.

The drug abuse issue among the youth in the herders’ community was mentioned by all the sources that spoke to HumAngle, including Bodala.

“They don’t go to a school that can teach them the differences between right and wrong. There used to be nomadic schools, but they are no more, and youth have been abandoned to drug abuse that makes them criminals,” he explained.

Same problem, endless fights

Thanks to the fertile lands, farmers in the agricultural region of Guri can work their fields all year long. Since the Hadejia river flows through Guri on its way to Yobe, it is possible to do dry season farming even when it doesn’t rain.

However, to care for their livestock, herders must travel from arid areas to places like Guri because not all of Northern Nigeria benefits from this abundant climate.

When herders are travelling, their livestock frequently stray into the farms they come across, which leads to clashes between them and the herders. Until the state government, led by Sule Lamido, established grazing routes for the herders and outlawed farmer land encroachment, there was conflict and even violence between farmers and herders.

Ibn Aliyu, a farmer in Guri, said that the issue had been momentarily resolved. He explained that the past government used to redesign the grazing routes every year and forbade farmers from encroaching on the herders’ lands.

The programme, according to Aliyu, was stopped by the new administration. “No redesigning was done for years, and that changed many things for the worse.”

People were compelled to convert the grazing routes into farmlands without considering the potential repercussions of the increasing demand for farmland brought on by a growing population. “When a herder who is familiar with his route takes it further and comes to a farm, problems result. He can’t control his livestock, so they’ll trample everything in their path,” Aliyu said.

Another aspect of the problem is that some farmers are selling their leftover produce to herders. “You’ll often find the farm in the middle of other farms, and the animals will have to pass through them to get to where the wasted produce was sold, and on their way, they destroy the other farms,” he explained.

Nevertheless, Aliyu asserted that this wasn’t always the case. He claimed that even though there is a route to some farms where the wasted produce is sold, the herders frequently decide to enter through other people’s farms and destroy them.

“Since they have been taught, even cattle are aware of right and wrong. They frequently follow their herders, who sometimes watch as the animals trample through farms,” Aliyu told HumAngle.

He said recent happenings have made farming harder for him. On rare occasions, he had to spend the whole day guarding the farm by himself, always worried about his safety. “Even this Friday, I spent my whole day there.”

Government not doing enough

The state government has come under fire from many Guri residents for not treating the conflict seriously. Hamisu Gumel, a resident of Jigawa, accuses the government of waiting for a tragedy to occur before rushing to implement short-term solutions.

“If the government is serious about solving the problem, it should prioritise it,” he said.

Farmers in Guri have also complained that the authorities don’t take serious action when violations are reported to them. They say police ask them for difficult-to-produce or real-time evidence when they report incidents, even when there is obvious evidence of destruction.

“There is no rule of law here,” Bodala said. “When a farmer and a herdsman engage in a disagreement, it is sometimes difficult to know what kind of legal procedure the local authorities used to deal with the infringers.” He explained that the absence of justice makes the situation worse.

According to Aliyu, this is why some farmers choose to take matters into their own hands. “Your farm was destroyed, but when you report to the police, they’ll ask you to provide video coverage of the attack even though you can physically show them the effect of the attack.”

The security officer who spoke to HumAngle, believes the government is doing what it can, but the problem is sometimes worse than it appears. He claimed that the few security personnel sent to Guri are not enough to handle the situation.

In Oct. 2022, a Nigerian soldier who had been sent to Guri to mediate a dispute between farmers and herders was killed. He was one of the soldiers who responded to a distress call from the Gagiya community, where it was claimed that herders had encroached on farmland.

Local journalist Abubakar Tahir Hadejia said the state government had attempted some reconciliation measures, but they had failed. He claimed that some of the government’s actions only serve to fuel the issue while appearing to be the solution.

“Politicians go out and give residents motorcycles, some of which are used to stage another attack,” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter