Cost Of Living Crisis: Nigerian Farm Labourers Suffer As Food Prices Rocket

People who have spent a decade displaced from their own farms in Nigeria’s North East have been finding work labouring on other people’s land. But now, the crisis in the cost of living has suddenly pushed basic staples out of reach of their wages.

As soon as he woke, Sanda Ali saw it was overcast and rain was coming …at last!

He grabbed his hoe and ran to the side of the road. In the drizzling rain, he joined a group of displaced people, all carrying their tools, as they gathered along the quiet Bama-Maiduguri roadside in Borno, North East Nigeria.

They all hoped a farmer in need of labour would stop and pick them.

But in reality, 51-year-old Ali is at best running to stand still. The current economic situation means however hard he works, he is being outpaced.

That morning, Ali was not able to eat any breakfast. He was not able to leave any money or food for his family either. The early morning cloud that stretched throughout the sky indicated to Ali that there could be a job today, and he must get going.

He had not been able to work for a month, not since the last time it rained.

In that time, the price of maize has leapt up by at least a third. No matter how hard he works, he will not be able to afford enough food to feed his family.

Powerless

While he was out of work and prices climbed, Ali was powerless to do anything. He could only pray for rain so that he might double his commitment to work on the farm to earn more.

But even if he was picked for a day’s work, doubling his commitment will not pay off. The money he will take home is less than half the price of a measure of maize kernels.

The group of men, women, and children anxiously waited. Some sat balanced on their hoes while others strapped them around their necks, in a hopeful display of exuberance and readiness to either plough or weed the fields and get money.

“We inherited farming from our parents and that is what we have been doing before the insurgents terrorised our village. After we fled to the city, we didn’t have access to farmlands and the only thing we did was to work on people’s farms and get paid,” Ali said.

At the beginning of the rainy season, labouring wages can be ₦1,000 ($1.27) per day, but after that farmers usually pay ₦500 ($0.62) per day, for weeding lines of crops. Later, at harvest time, wages increase again.

As soon as Ali is paid the small amount of money he gets from this backbreaking work, it is swallowed by the current hike in food and fuel prices.

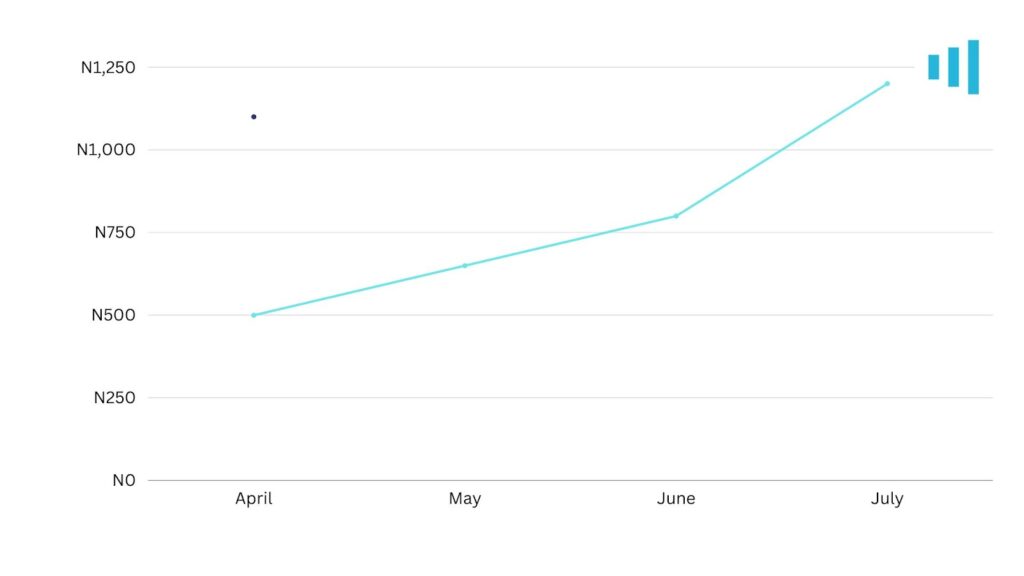

In April, the cost of grain was ₦600 for a mudu (approx 1.5kgs). In July it had all but doubled to ₦1,000. That is for the lower quality grades of grain. Cleaner grades, sifted for small rocks and dirt, cost more.

A family the size of Ali’s could consume more than two mudus every day, in better times. One measure of rice per day is struggling.

“I can’t afford to buy one mudu of maize because it has inflated,” he said.

“What can we do? No one is supporting us and we can’t go back to our villages yet, the insecurity is still there,” Ali told HumAngle.

Sometimes farm owners take pity on them and compliment wages with a few kgs of grain, maize, millet or guinea corn.

In order to make ends meet, Ali’s children beg on the streets. They are dependent on charity from friends or relatives.

‘On our own’

Ali and his family fled their village Kayamla, a remote village in Konduga local government area of Borno, about ten years ago.

Today it is still dangerous and nobody has yet returned there.

Ali currently lives with his wife and five children at an uncompleted building in Dalori community along Bama Road. He moved there last year when the camp they were living in, NYSC IDP camp, was shut down by the Borno State government in an effort to resettle displaced people back to their original communities.

According to Ali, when the NYSC camp was shut down, they were all taken to Auno village, along Damaturu-Maiduguri Road.

“The government carried us to Auno and said they will give us a house but when we went there, me and my family did not get a house and a month later we travelled back to where we are now,” he said.

Ali paid ₦10,000 ($12.71) for rent in Auno for the period of their stay hoping to get the house the government promised them. “The commissioner visited us and gave us money to rent a house before they issued us a house, but we waited and nothing happened so we left,” Ali told HumAngle.

“Since our camp was closed, we did not have anywhere to go and our village is not safe yet so we stayed back,” Ali said.

He added: “We used to have access to food assistance and other forms of humanitarian aid when we were at the camp but, since it was closed, that was the end of it and we have been on our own.”

“Government should restore security and take us back to our villages where we own our own farmlands, cultivate and harvest it,” Ali said.

Many Internally Displaced People have lived in rural areas all their lives. Living in urban areas is difficult for them. In times of humanitarian crises where access to food and shelter has become nearly impossible.

Living conditions for people who have been displaced from their homes, living in camps or makeshift shelters for almost a decade, are changing day by day, he says.

Ali and his family have struggled to find somewhere they can fit in. “There is no work in the city, we find it difficult to accommodate with the system, we don’t know people,” he said.

Alaji Mohammed, a 19-year-old man whose father and mother were killed by Boko Haram, also joined others on a quest to work on the farm to get money that he can use to provide food for his brothers.

He lives with his uncle, who is also displaced. Everyday is managing the little they get. “It is compulsory for me to work hard on the field and get paid. My uncle whom we stay with, cannot satisfy all his children, talk less of me and my three younger brothers. This is why I look for a job here and get money to complement my uncle’s effort” Alaji said.

“Everything is expensive now and we earn little from the farm work. Many times we are not picked by farm owners because of our age and even if they pick us, they underpay us” Alaji said.

Alaji started crying when narrating how his parents were killed, he sobbed in silence for a minute before he summoned the courage to speak to HumAngle.

“Boko Haram killed my father in front of us when they attacked Banki about seven years ago. They beat him to death, we were all seeing how they did it. Our mother too died later because of injury she got as a result of how Boko Haram battered her while attempting to rescue our father.

My brothers and I have fled since then and stayed with our uncle wherever he goes.” Alaji said.

Alaji and his uncle were living at Dalori II IDP camp until the government shut it down last year. It has been tough for Alaji in this time when prices of food continue to hike day by day.

“The maize we were buying before has almost doubled its price this year and hunger is everywhere, we need assistance,” Alaji said.

Race

Falmata Goni, a 60 year old woman, joined the race to find work too.

“We are lacking what to eat and I am excited that I will work and get paid a little. The diligence and perseverance that comes with our age gives us an advantage and we are picked quickly by farm owners, it is good to capitalise on these advantages.,” she said.

“Prices of grains are inflating too much and there is nothing we can do about it,” Falmata added.

Tumber Philip, a food stuff trader for over 30 years in Maiduguri, commented on the frequent rise in food prices like maize and millet. “The sudden rise in prices of food is shocking and we recorded a continuous rise in prices of goods like maize in the past two months. This phenomenon is largely caused by the hike in prices of fuel in recent times,” Tumber said.

A couple of months ago 1.5kg of maize cost ₦700 ($0.88) just a couple of months ago but today it costs ₦1000 and in some places ₦1200 ($1.52), he added.

Life is becoming tougher and tougher day by day for displaced people as the consequences of hike in fuel prices continue unfolding in the country, many of them that don’t have access to humanitarian aids or assistance from family and friends are depending on what fate has for them.

Just life?

On that rainy Sunday, a farmer came and picked up Sanda and four other young men.

But when they reached the farm, Sanda and one of the boys were dropped because the farm owner complained that he could not pay them all.

Sanda returned home with nothing for himself or his family that day.

As he told HumAngle: “The work demands energy but what can I do?”

“I normally go out three times in a week but now I must add more days so that I can earn more. How many days do I need to work to earn money that can feed my family? This is just life,” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter