Contagious Skin Disease Plagues Borno’s Displaced Community For Over a Year

For over a year, a displaced community in Nigeria’s Northeast has been plagued by widespread, contagious skin diseases. Despite several attempts to treat the outbreak with traditional and modern medicine, no cure has been found.

There is an alarming health crisis in the Low-Cost displacement camp in Damboa town, Borno state, northeastern Nigeria. The camp was established nearly a decade ago, following the terrorisation of several communities in the region by terrorists. It now shelters about 1,500 households, comprising more than 7,000 displaced people who fled from over four remote communities in the area.

For over a year, the camp has been plagued by a widespread, contagious skin disease. Despite several attempts to treat the outbreak with traditional and modern medicine, no cure has been found.

Residents told HumAngle that the disease has affected more than 500 people, including adults, nursing mothers, children, and infants. Day by day, the epidemic continues to spread across the camp, leaving a trail of suffering in its wake.

Abaku Babagana, 48, once lived peacefully with his two wives and eight children in the camp. However, their lives were upended when the unidentified skin disease began to spread.

In the section of the camp where Abaku and his family reside, hundreds of tarpaulin tents stretch across the area, and only a few households have been spared from the disease.

“You will see almost everyone, young and adults, scratching their bodies while they walk or rest,” Abaku said. “Some experience mild symptoms ranging from itching to severe symptoms that include skin rashes, soreness, fever and lack of sleep at night due to irritation.”

Most of the people affected are infants and children who transmit the disease to their mothers and then to every member of the family, according to Abaku. The skin disease epidemic started about a year ago, and it gets worse and more widespread every month.

“We visited the health centre managed by Medicine du Monde [a humanitarian organisation] for treatment, but it was ineffective,” he said. “When they give us drugs, it only suppresses pain, but it doesn’t stop the spread; the infection will infest all parts of the body. No one has gotten treated for the skin disease since it started.”

Explaining how his family contracted the skin disease, Abaku said it all began in his first wife’s tent after the birth of their youngest child. The newborn is suspected to have contracted the disease through an infected visitor who may have cuddled her.

“In my first wife’s house, we are a family of six, and all of us have contracted and are suffering from the skin disease,” he added. “Typically, it starts from your hands, and then spreads all over your body and eventually begins to sore the skin.”

Abaku explained that finding effective treatment for the disease has been challenging. “The only remedy we employ since hospitals could not solve the problem is to bathe regularly and apply traditional medicine. With all that, the disease has not stopped. We started visiting the NGOs’ health centres for the past five months since my family contracted the skin disease, but not everything has improved.”

Abaku’s second wife is free of the disease, making him take desperate measures by refraining from visiting her and the kids to avoid infecting them, but it is not a long-term solution.

His experience of displacement is unequal to this challenging health crisis affecting his family at a time when they are rebuilding their life after losing so much in the past. According to Abaku, he has never experienced this kind of health crisis before.

From bad to worse

“My story of displacement started when Boko Haram attacked our village about ten years ago. We fled to Sabon Gari and stayed for four years, then eventually fled again to Damboa town, where we settled at the low-cost displacement camp for the past five years.

“I have never seen something like this,” Abaku added. “It is like a wildfire, starting from one point to another. I must say that this health crisis has really disturbed us; we need help.”

Ali Kuloma’s family, residing a few tents away from Abaku, contracted the disease two months ago. While it continues to spread, only three members of his family have contracted the disease at the time of filing this report.

“We cannot stop scratching our itching bodies, and as a result, we peel our skins, leading to blood everywhere on our bodies. We stain our clothes with blood. We cannot sleep at night because of the pain and the urge to scratch our bodies,” Ali said.

Ali, 41, has two wives and eight children. His greatest fear is the relentless spread of the disease at their camp. “We are praying for urgent intervention from government and non-governmental organisations to support us from this epidemic,” he said.

For Aisha Bukar and her family, who fled Sabon Gari five years ago, the situation is equally dire. Only her husband is spared, mainly because he has been away on a business trip for over a year. When the disease infiltrated her family four months ago, it began with one person before quickly spreading to the rest of the household, including Aisha and three children.

Despite her best efforts, Aisha has been unable to find a cure for her family. She sought help multiple times at an NGO-operated medical facility in Damboa town, but the disease has only worsened with time. Each passing day brings more suffering for her and her loved ones.

Aisha doesn’t know how, but she was the first to get infected, followed by her children. “I developed an itchy body four months ago, and now everyone in the family is affected, except my husband, who has been away for a long time,” she said.

No cure, no relief, but hunger

Aisha explained that her family consulted health centres, but they were only given ointments and other drugs that have remained ineffective. For the past year, displaced communities living in makeshift camps and host communities across the region have suffered from various contagious illnesses that remain untreated.

HumAngle’s findings revealed that some of these illnesses have plagued displaced communities for more than a year, coupled with malnutrition.

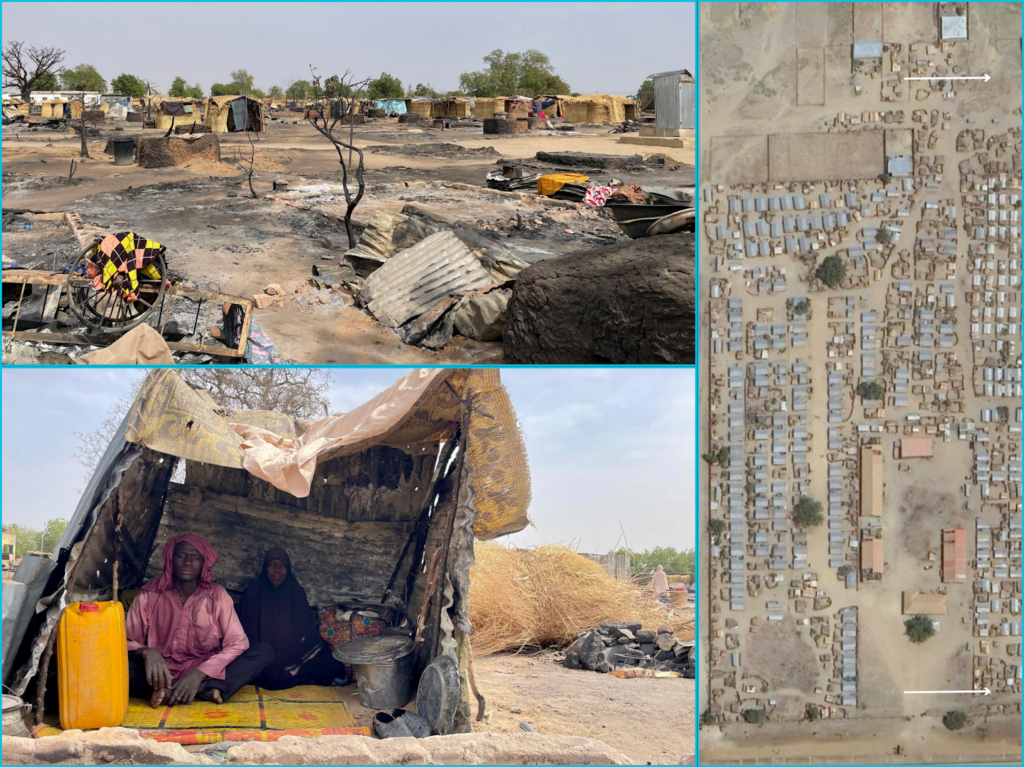

The Muna Kumburi displacement camp in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, shelters over 7,000 individuals. The camp has endured devastating events that have plunged many families into desperation.

In March 2024, a fire outbreak razed the entire camp. Just months later, in September, the great Maiduguri flood destroyed thousands of shelters in the camp.

Malum Yasami, the chairman of the camp, told HumAngle that humanitarian assistance had ceased in the camp long before these devastating events. He noted that it has been nearly a year since the camp last received aid. “Before the humanitarian organisation ceased assisting us, the smallest household with a family size of five used to receive a minimum amount of ₦25,000 every month. But all these have stopped for the past year,” Yasami told HumAngle.

Other residents also noted that a large family typically received an average of ₦70,000 each month, and this humanitarian support was rendered to the camp for about four years until everything eventually ceased.

These events have plunged families and individuals in the camp into a severe food crisis. Malnutrition now affects breastfeeding mothers, children, and even adults.

Yana Falmata, 67, shared with HumAngle what life is like for her, struggling to survive the crisis. Yana said, “Before, my neighbours used to give me food, but now everyone is on his own. They could not feed their family. How could they help me? We sleep and wake up with hunger; begging too is hard because no one will give you something that will be enough,” she lamented.

Yasami painted an even grim picture. “We are in desperate need of food intervention,” he said. “Hunger is killing children and adults. People don’t know where to get food or support. Children and adults who are affected by malnutrition are suffering, and the number of people affected is increasing day by day. It is really alarming.”

During HumAngle’s visit to the camp, the extent of the food crisis was painfully evident. Silence hung heavily in the air, broken only by the cries of hungry children. Inside the tents, mothers and adults appeared emaciated, yawning from exhaustion and hunger.

Children wandered, clutching sachets of Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) distributed at a distant health centre operated by a non-governmental organisation. Meant for children suffering from severe and mild malnutrition, the RUTF was often shared with adults desperate to stave off hunger.

“It is hard to get the RUTF even if your child is suffering from hunger disease,” said a nursing mother. “The process of accessing health services is also very hard, and we must trek a long distance. Several times, I come back empty-handed and unattended.”

‘Feeling marginalised’

With no other options, some camp residents undertake the dangerous task of venturing into the bush to gather firewood to sell for food. However, this activity comes with significant risks. Recently, we reported how members of the camp are frequently abducted or killed during those trips.

Despite the recent efforts of Borno State’s flood relief committee to disburse funds to households affected by the Maiduguri flood in September, camps like Muna Kumburi, which also suffered extensive damage, have been excluded. This omission has left residents feeling abandoned and marginalised.

“The flood has damaged our tents, but no one in the camp was considered for compensation or financial assistance like the others in town,” Yasami lamented. “No one visited us to assess the impact of the flood in our camp, which really made us feel marginalised.”

When HumAngle contacted Abdullahi Umar Ibrahim, the Borno State Emergency Management Agency spokesperson, he said, “[The agency] would reach out to our focal persons in Damboa and proceed to take necessary action.”

He added that the agency will keep HumAngle updated as soon as possible.

The Low-Cost displacement camp in Damboa, northeastern Nigeria, is facing a severe health crisis due to an uncontrollable contagious skin disease affecting over 500 residents.

Despite attempts with both traditional and modern medicine, no effective cure has been found, causing suffering among adults and children, with symptoms like severe itching, rashes, and fever.

This health crisis exacerbates the difficult living conditions of displaced persons already battling malnutrition and a lack of basic needs due to halted humanitarian aid.

Additionally, residents in the Muna Kumburi displacement camp in Maiduguri are suffering from hunger and malnutrition after natural disasters destroyed their homes.

Humanitarian assistance stopped nearly a year ago, causing immense food shortages. People feel marginalized as they have not been included in relief efforts, and survival now often involves risky ventures like collecting firewood.

Calls for urgent aid continue as the crisis worsens.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter