Conservationists Push Back Emerging Threats Against Yankari Wildlife

The Wildlife Conservation Society in Nigeria is actively involved in saving one of the last surviving pristine homes of diverse endangered wildlife threatened by poachers, criminal gangs, and oil explorers.

The loud crunching sound of dry leaves beneath boots suddenly went cold as the expedition came to a halt. A group of armed rangers had quickly transitioned into hand signals, communicating quietly before splitting to investigate a potential breach inside the Yankari Game Reserve.

On this sunny day in late January, the expedition team had set out to search for elephants using the geolocation from their satellite collars. The journey began very early from the Wikki camp, which houses staff and visitors — pausing briefly at the Duke wells used for storing water during the slave trade — and winds up at a temporary camping site a few minutes past 7 a.m.

After having a breakfast of tuwo and okra soup, the first pickup truck departed for the main entrance, with the accompanying party following behind in a land cruiser truck suitable for the search terrain. On the way, the rangers noted the elephant footprints and dung, using that to estimate when they passed and their likely direction. Tracking them was an arduous task, partly because they appeared to have been moving.

At one point, the search party decided to ditch the vehicle and walk to Batta, a water spot for animals fed by the overflow of the nearby seasonal river Yashi. The river also flows into Gaji, a major river that cuts through the reserve.

Getting there required navigating thorny vegetation and struggling with stingless black bees buzzing as they hovered around your head. The reserve’s Savannah landscapes, with sandy loams and clayey soils, were unique. Some areas had shrubs like the Aduwa, a desert date plant, and others had giant trees, such as the Baobab.

As we moved, all of a sudden, the ranger in front signalled with his hand and everyone stood still. He was trying to make sense of a sound. Shortly after, the all-clear was given to continue the mission to find Yankari’s elephants.

The team would later come to a halt again. This time, a human intrusion was detected through voices carried by the wind. The senior ranger quickly rallied his colleagues armed with shotguns, and a tactical plan was rolled out. They divided into two-person teams and moved in separate directions to outflank the intruders while another ranger remained behind with the rest of us.

After some time, one of the teams returned, but the chase was unsuccessful. However, they found their footpath and reason for the incursion, which was to collect gum arabic from the Acacia trees. The second team returned much later; a single shot was fired to alert them that it was time to regroup.

It took us over 20 minutes after the incident to arrive at Batta. There were no elephants, just their giant marks in soft sand and plenty of dung. It was not a lucky day. Yankari is estimated to have the most extensive surviving elephant population in Nigeria and one of the largest remaining in West Africa.

A combination of factors, including hot and sunny weather, hindered sighting. It’s possible they may have taken a different course from the trajectory followed, or they got held up chewing food.

“We estimated the population of elephants to be approximately 100. It is quite difficult, as you can see, to see the elephants, and obviously to count them is even more difficult,” the Country Director at Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Andrew Dunn, said in an interview.

The population had declined significantly from its peak due to hunting. Many years ago, when it was still a national park, there were reportedly 300 to 350 elephants. Andrew says the good news now is that poaching has stopped, and they expect recovery.

Even so, he says that “it will be a slow recovery” because of their low reproduction rate.

“As recently as 2006, there were as many as 350 elephants in Yankari, but a period of heavy poaching from 2006 to 2014 reduced their numbers dramatically,” the association mentioned in a 2019 report.

A conservation island in Nigeria’s savannah

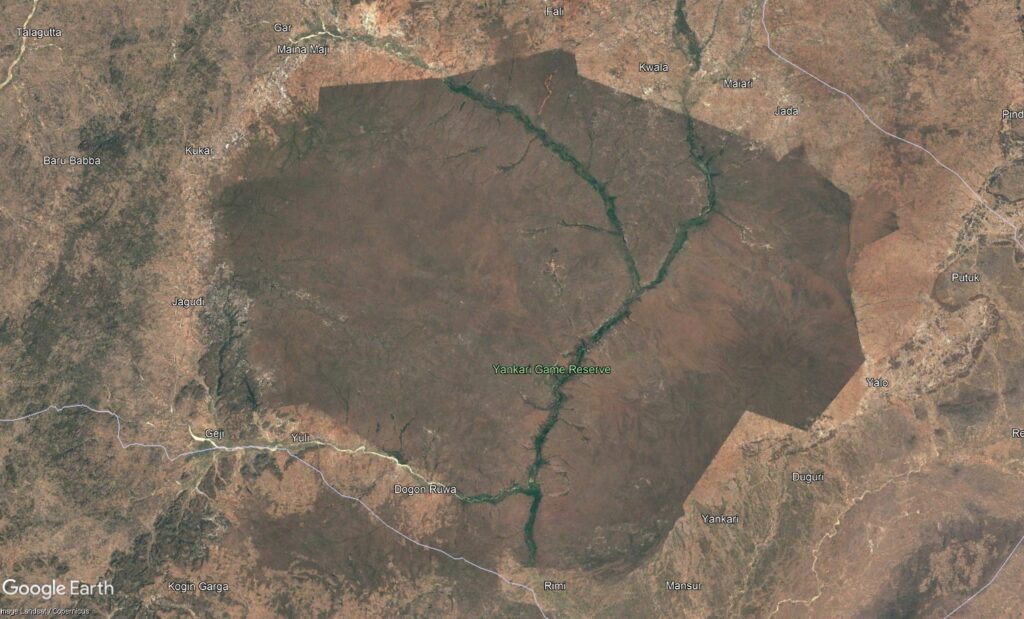

Initially established in the 1950s as a Game Preservation Unit of the Northern region, Yankari stands out as a vegetation island, spanning 2,244 km² in the Alkaleri area of Bauchi.

It was handed over to the federal government and converted into a National Park in the early 1990s. However, it reverted to state control in 2006. The state government in 2014 signed a co-management agreement with the WCS, expanding a relationship that dates back to 2009.

The tarred and sloppy road connecting the entrance gate at Mainamaji village and the second gate at the Wikki camp is over 40 km. It gives a glimpse of the landscape. There are road signs telling drivers when to move at 50 and 30 km/h alongside several animal crossing signposts.

The caution is also to safeguard the animals coming to drink water from the depressions created during the road construction. In the camp, they have facilities to support operations and accommodate guests.

The animals here are easily spotted; a couple of warthogs roamed near the chalets. After a bit of searching, a group of baboons notorious for grabbing food and soft drinks from people were found resting at the Wikki natural warm spring.

There are four warm springs in the reserve; Wikki, Dimil, Gwana and Mawulgo and one cool spring, Tungan Maliki.

The camp also has an airstrip constructed with gravel for the operations of Cessna aircraft used for monitoring.

Not far from the runway, the team with me spotted Hyena footprints on a track that leads into other parts of the reserve and a waterfall. The carnivore hunters are famed for moving around at night and making noises.

The animal population of Yankari includes a delicate and endangered species of wild cats. Recently, a large male lion was sighted at the edge of the reserve. That discovery has sparked renewed interest.

The WCS country director explains that they are rarely seen. “It’s like the lion population is very small. It could be roughly five but certainly less than 10.” The problem, he says, was that in the past, there was a lot of illegal livestock grazing, and combined with a lack of natural prey to eat, it made them rely on feeding on cows.

Because they couldn’t finish a carcass in one sitting, it created a risk of poisoning when they returned. The worry is they have become accustomed to feeding on cows, which is what he was looking for. Andrew also says that hunting levels are down and natural prey species such as antelopes and buffalos have increased, but they haven’t seen a corresponding increase in the lion population.

They plan on bringing a lion expert to conduct an assessment, which could allow collars to be put on them and help in understanding why they are not increasing.

Another wild cat in the area is the leopard. A surprising finding was shared in 2017 after a camera trap recorded one. They were previously assumed to have gone extinct in the reserve, with no record of them for 10 to 20 years.

There are other animals in the sanctuary, including waterbucks, hartebeest, bushbuck, and hippopotamuses. It is also home to diverse species of birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles.

Wildlife security faces a pyramid of threats

The network of dirt roads, sometimes requiring moving through canopies formed by vegetation, gives the rangers access to patrols against intruders. Some tracks enable safari trips for tourists to observe the wildlife and landscapes, providing valuable conservation education and revenue opportunities.

The WCS is currently using a bulldozer to refurbish some of these tracks, which would enhance monitoring.

Yankari is a biodiversity island due to the human buildup and activities around it. However, that unique feature creates a mountain of threats and vulnerabilities that the rangers and management must confront regularly.

The challenges range from the illegal gathering of non-timber forest products and felling trees to hunting to supply the lucrative bushmeat and wildlife parts market.

Rangers equipped with kits, including VHF radio, conduct routine patrols and camp in different locations to counter threats. Between July and Sept. 2022, 35 patrols were completed by rangers covering a total distance of 3,713km.

The capacity-building programmes for personnel have also strengthened their readiness. A senior game guard ranger, Suleiman Saidu, said the training received has made a difference, enhancing firearm handling, patrol and bush camping, in addition to improving engagements between rangers and communities.

“It’s difficult, but because it’s my work and I promised to do it, that has made it easier for me,” said another ranger, Ibrahim Haruna. He described the biggest challenge as the hunters disturbing the animals, “[but] we try our best to catch them”.

Last year, about 44 persons were arrested for unauthorised activities. Twenty-three poachers were arrested in 2020 and 35 poachers in 2019. Those arrested included a gang of seven poachers with an AK assault rifle and other dangerous weapons.

The collars on the elephants help keep personnel in close contact at all times. This is critical to discourage poachers because they spend a bit of time on the edge of the reserve.

It also acts as an early warning mechanism to mitigate the invasion of farms. The encroachment of farmlands into the reserve and elephant routes has increased the risk of crop raiding and conflicts.

Another intervention to de-escalate tension was the formation of elephant guardians, trained to alert authorities. A 35-year-old guardian and farmer, Tanimu Muhammed, explains that they observe their movement and notify the authorities. “Before, we didn’t have the watch tower. After it was built, we stayed on top, watching.”

When the sound of the herd approaching is heard, they call for backup, and a vehicle and personnel are dispatched to push them back.

WCS project manager Nura Nuradeen Ahmed also explained that an ongoing trail project is being used to curb the conflict. Some selected farmers have been supported in setting up a beehive fence to protect their crops, as elephants are afraid of honeybees.

They reckoned that the farmers would also make alternative income from honey and comb.

One reason wildlife and environment crimes have persisted is gaps in the conservation laws, mostly enacted decades ago. They are usually weak and unable to deter violation. Nuradeen Ahmed pointed out that his organisation is trying to work with the authorities in Bauchi to improve the legal framework.

An investigation by Premium Times last year noted the dangerous impact of weak laws and punishment. It highlighted that poachers arrested in the past returned to hunt in the reserve after being “allowed to escape from custody or (are) released after paying a very small fine only”.

The report also reviewed WCS records which showed that between 2013 and 2021, 418 poachers were said to have been arrested, but only 272 were prosecuted. It revealed that “in 2013, after several animals were found dead, including seven elephants with their tusks missing, hunters arrested that year received sentences of between six months to 18 months in jail.”

In another instance, years later, hunters found to have several animals, including hartebeests, hippos, baboons and patas monkeys, were jailed for between two and 18 months. First offenders also got fine alternatives as low as ₦30,000.

The international dimension of trafficking of wildlife products from Nigeria or transiting through Nigeria was evident in March 2022 when a Vietnamese woman was found guilty of importing over 1,000 elephant tusks from Nigeria. The tusks had been disguised as packages of groundnuts.

Traffickers are adopting innovations to keep pace with law enforcement. The Nigerian Postal Service, between 2015 and 2016, intercepted 23 elephant tusks weighing 485kg and worth ₦459 million at the time. The products concealed in parcels were detected and intercepted during screening.

Nigeria’s parliament is working on addressing the legal gap being exploited to cause havoc. A bill seeking to conserve and protect endangered species from extinction and trafficking recently passed its first reading in the House of Representatives.

It’s reported that when signed into law, it would increase penalties to reflect the seriousness of crimes and their impact on endangered species and expand courts’ ability to expedite wildlife cases.

Emerging threats to wildlife security

The threats facing Yankari’s ecosystem have taken on a new dimension in recent years, with a series of attacks in communities around the reserve and the exploration of hydrocarbon resources a couple of kilometres away.

Several incidents of kidnapping for ransom and raiding of communities have been recorded. In early January, the police reported that two AK rifles were recovered during an operation that led to the killing of three kidnappers terrorising Alkaleri and taking cover at the Games Reserve.

At least 20 people were killed in December during an attack in the area. The casualties were recorded in the Rimi community, located about 1.5 km from Yankari. Earlier in the month, twelve members of an armed group were killed in a firefight with security forces in the Alkaleri forest.

The insecurity is an issue that is concerning and could jeopardise efforts to preserve the reserve’s biodiversity. The use of assault rifles by the attackers also creates a major challenge to the rangers equipped with shotguns.

The situation requires decisive government action to prevent the establishment of harbour areas and a fate similar to that of several conservation areas in the northern region.

For instance, the Sambisa Game Reserve, which is the only Gazetted Game Reserve in Borno state, was known to have a diverse population of wildlife, including elephants. However, in the past decade, it became infamous for providing sanctuary to Boko Haram insurgents and the focus of military operations against the group.

In the Northwest, terror groups notorious for targeting villagers and commuters operate in the Kamuku National Park located near the Birnin Gwari area of Kaduna and the adjacent Kwiambana Game Reserve in Zamfara. They share a similar ecosystem and are separated only by a natural boundary – the River Mariga.

The violence has extended into Kainji Lake National Park in the Northcentral. The park near the border with the Benin Republic is the second location known to have a lion population in the country.

Another problem looming around the corner is ongoing oil and gas exploration in the Kolmani river field in the Upper Benue Trough between the northeastern states of Bauchi and Gombe.

The founder of Surge Africa, Nasreen Al-amin, in a previous interview, told HumAngle any extractive activity within the axis of the Yankari Game Reserve threatens a very fragile ecosystem. She further highlighted its importance as a biodiversity hotspot where many endangered species continue to thrive.

At least one of the oil drilling sites in Alkaleri is located about 16 kilometres from Yankari, raising concerns about negative impacts on the local ecosystem.

There is a risk of contamination of the river Gaji because the river that flows near the drilling sites is connected to it. The noises and other activities, such as vehicular movement, can also be a menace for the animals.

The unsustainable depletion of forest cover, a critical carbon sink, and the loss of wildlife safe havens in northern Nigeria increase the importance of Yankari. Protecting the reserve would preserve the ecosystem and provide economic benefits for the communities in the area.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter