Conflict And Period Poverty: Rags, Leaves For Menstruation In Benue IDP Camp

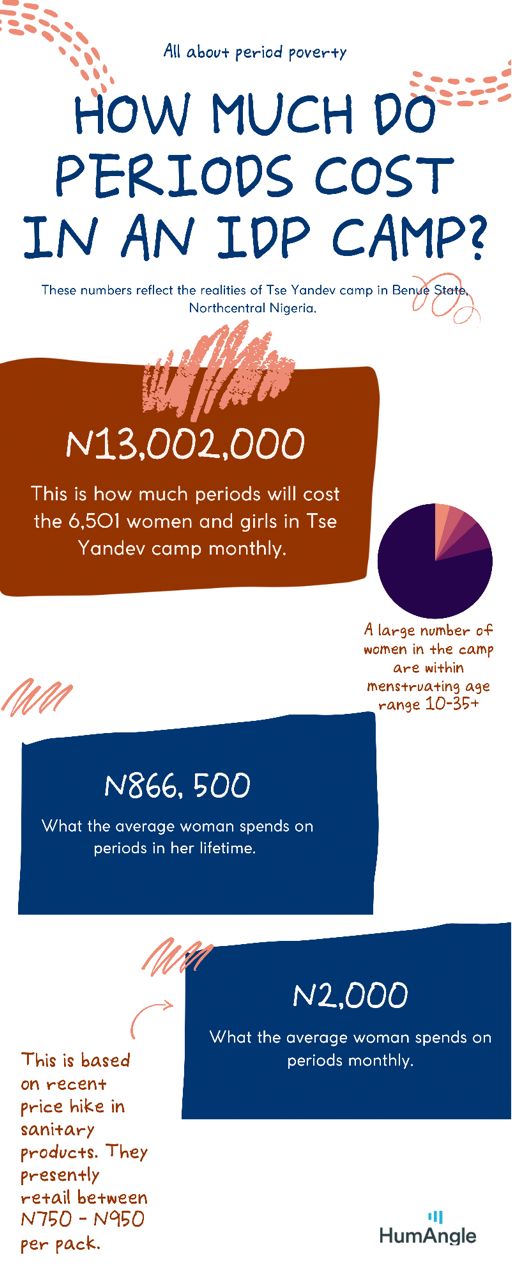

The women at Tse Yandev camp, Benue in North-central Nigeria, need at least ₦13 million monthly to buy sanitary products for hygienic menstrual periods. But the conflict-induced period poverty is heightened by their lack of basic needs — food, shelter, clothing and safety.

Like most girls, 21-year-old Priscilla Mtswenem started menstruating as a pre-teen and soon learned the basics of keeping personal hygiene during the period. Her parents provided her needs from their proceeds as farmers. She had money for sanitary products and access to get them. Priscilla’s biggest problem during her period was managing light cramps as she went on with her schoolwork.

Soon, Priscilla, her family, and others from her village, Mbaguen, in Benue State, North-central Nigeria, had to run for their lives. When conflict happens, victims are focused on surviving, forgetting everything else.

Since 2013, attacks by criminal herders and farmers over land and grazing areas have escalated in Benue. The state has an economy that is driven by agriculture, and in the wake of the conflict, a lot of these farmers have been displaced from their hometowns, where they controlled large farmlands.

Most of these people are assembled in a makeshift shelter along the North Bank area in Makurdi, the state capital. In the camp, Tse Yandev, women like Priscilla have to improvise monthly, using rags and large leaves in extreme cases to hold blood during their monthly periods.

A new monthly reality

“I use rags. There are women here who use leaves,” Priscilla says in the Tiv language, rolling the hem of her wrapper with her head down. Before answering this question, she had talked calmly but confidently about her experience during the attacks and how her family fled. But exploring the issue of periods suddenly made her shy as it is considered too private in several cultures.

For her, life was much easier when she just collected money, without exactly saying that she was going to buy sanitary products with it. This is one of the prices conflict survivors pay.

“I was in my village with my family and one day, we were on the farm and heard that there was an attack somewhere where some people close to our place were killed. Some houses were burnt, so my family decided to leave. They were killing and came close to our farm. They killed many women and I can’t mention them because there are many. I was in secondary school but due to the crisis, I stopped. I have not done my WAEC exam due to this crisis.”

Not only did she lose the resources for the inevitable monthly expense, she and other women in the camp also lost their privacy, which is crucial for women during menstruation for several reasons.

In the University of Oxford’s Sanitary Pad Accessibility and Sustainability Study, the importance of using pads and sanitary products for the sake of privacy is emphasised. “Privacy is what pads promise.”

“In places where a girl who has menstruated is seen as ready for marriage or fair game for sexual attack, the ability to keep the community from knowing if and when it has occurred can make all the difference. Maintaining the secret means not only helping the girl from avoiding ‘accidents’ but keeping the world from knowing when she washes, changes, dries or disposes of whatever menstrual method she uses,” the report adds.

Girls like Priscilla cannot maintain privacy during that time of the month in the camp. Displaced people at Tse Yandev camp sleep in small makeshift shelters made with mosquito nets and tarpaulin. The huts are built with sticks, bents and laid on top in rows. Then the nets are cast over them. The spaces are cramped and very small, even for one person. Yet, when HumAngle visited, families were camped inside at night, looking forward to sun-up so they could finally stretch their legs.

At 6 a.m., the camp was bustling and filled with life, with the women already dressed for the day having had their baths shortly before dawn, under the cover of darkness. They began their daily struggle of looking for what to feed their families with.

Priscilla came to the camp with 11 other family members. “We are 12 that escaped in my family and we live in three huts. Everybody sees everybody,” she said.

In arrangements like this, it is difficult for girls and women to maintain privacy during periods. They have to keep looking over their shoulders and reduce the vigour of physical activities in fear that the rags might shift and properly announce to the other members of the camp that they are on their periods. But there is more to worry about.

Choosing life, maybe…

The Oxford study took note of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa where girls use cloth scraps for periods, like in Tse Yandev camp, and noted the medical risks.

It says, “As a practical matter, weather conditions — especially in humid equatorial countries prevent cloth from dying completely even if left in a sunny spot. As a result, the rags are often damp and may have debris clinging to them when returned to use. After a while, dirty menstrual cloth gives off a distinctive smell and the personal hygiene poses a health risk.”

Like Priscilla, Beauty Deior, from Torkula village has to weigh between getting food for her three children and buying sanitary products for her periods. She chose the former as do the other mothers in the camp.

Beauty looked tired and out of breath when HumAngle interviewed her. She was preparing to go to the rice mill to gather chaffs to feed her children. When she ran from the village with her husband and children, there was no time to pack anything. They were running for their lives. She is still having to pick life over menstrual hygiene.

When asked about the products she uses for her periods, she was initially startled over the question. Then she stared straight at the HumAngle reporter, as though squaring for a confrontation over her choice to feed her children first. Hearing no rebuttal, she relaxed her shoulders and explained further.

“Getting money is difficult. When we go outside to work, some people treat us badly. So the little money I get, I use it for feeding and then use rags for my monthly periods.”

How much do periods cost?

The prices of sanitary pads in Nigeria have moved from ₦350-₦400 in 2019 to ₦700-₦950 in 2021.

The monthly cost of periods depends on the brand of sanitary towels, tampons and/or menstrual cup that the woman is most comfortable with if she is in a position to choose. There is also the cost of new underwear and another for pain relief, for women who have painful periods and still need to go about their day.

The average woman menstruates from age 13 until age 51, about once a month, with each period lasting from three to seven days. This equals at least 456 periods over a span of 38 years, which amounts to roughly 6.25 years or 2,280 days of her life spent bleeding.

Conservatively, a woman would spend at least ₦2,000 on periods monthly and ₦866,500 in her lifetime supposing she just has to manage two packs of sanitary products every month and not spend on anything else for the period.

For displaced women and girls, this amount would be prioritised towards food and sustenance, rather than sanitary products.

According to data made available by the camp officials, in Tse Yandev camp, there are 6,501 women and girls between the ages of 10 and 35+, the age range for active menstruation.

The above cost for periods per woman, when multiplied by this population, rounds up to ₦13,002,000 monthly. A camp that lacks basic housing and food for displaced people is most unlikely to have access to this much for periods.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter