Climate and Conflict Are Straining Minds in Nigeria’s North East

Across Borno State, the slow violence of environmental degradation and protracted conflict is leaving farmers, herders, and fishers not just displaced, but mentally broken. Psychiatrists warn of a silent epidemic of trauma and despair.

Kaka Ali once came close to ending his life.

The 27-year-old farmer, displaced by conflict in North East Nigeria, said he lay restless on a thin mat in the ‘Water Board’ displacement camp in Monguno, Borno State, his mind crowded with unpaid debts and hungry mouths. Collectors showed up at his tarpaulin shelter and cornered him in the market, demanding the ₦10,000 he owed, an amount he once considered pocket change.

“It was crazy of me to have thought of that,” he says now with a chuckle. “It was merely ₦10,000. I could have given that as alms during the harvest season in the good old days.”

Across the region, farmers, fishers, and herders are facing a slow, compounding collapse of livelihood, security, and mental stability. Climate shocks drown or dry their lands. Terrorists chase them from their homes. And in the absence of formal psychological support, a silent epidemic of mental distress festers.

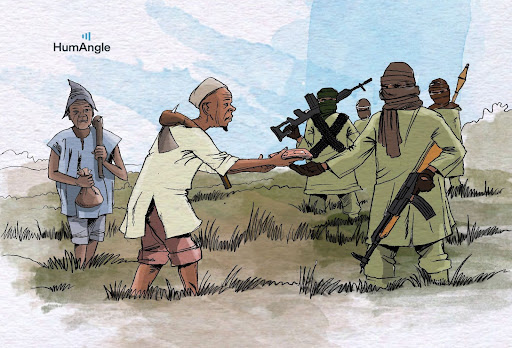

I first spoke to Kaka last December, when he talked about taxes and threats farmers endure from the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) in Northern Borno. Since then, he has called regularly; sometimes at dawn, other times long after the night prayer. So have Aja Bukar, a farmer from Auno, a town on the outskirts of Maiduguri, who spoke to HumAngle in October, a month after the devastating Maiduguri flood turned his life upside down. And Yusuf Usman, a fisherman from Baga who described the routine extortion that fishers face along Lake Chad.

Over months of interrupted call signals and small check-ins, they began to share more than facts. They began to speak as people searching for understanding.

A crisis beyond the visible

In Nigeria’s North East, where climate change impacts intersect with violent conflict, the crisis runs deeper than the surface. Beyond the overwhelming heat, dry spells, and abandoned towns lies an invincible but equally devastating toll: psychological trauma. While policymakers debate arms purchase, dwindling water levels and aid packages, people here are quietly being stripped of peace, dignity, and the will to continue.

Kaka’s struggle is not about money alone. It is about meaning. Once a respected millet and sorghum farmer, he is now stuck in displacement, paying to access his land. He borrows, repays, borrows again. With each cycle, his sense of agency erodes. The land is no longer generous; ‘farming permits’ keep increasing.

Across Borno and the rest of northeastern Nigeria, stories like Kaka’s are common.

Aja remembers when the soil in Auno was fertile and dependable. Now, what remains is sand and loss. “In those days, we had good loamy land,” he says. “The farm was more than ten hectares. I once harvested ten bags of beans. It was the peak.”

Today, the land yields very little. The failed harvests are not just economic failures; they are emotional defeats. These are not just food shortages; they are seeds of depression, anxiety, and grief growing quietly beneath the surface of droughts and raids.

Yusuf remembers when the water was kinder. However, the population of the fish has dwindled. “We could hardly catch a third of what we used to in previous years,” he says. “This has significantly affected our income. Fishing is our core profession. Very few of us complement it with small-scale farming. Flooding also destroyed most of our crops late last year. Someone who could comfortably take care of ten people can hardly cater for two today. We are also frequently disturbed by the terrorists. It is mandatory to pay tax when we go to the shore to fish. Farmers are not left out either.”

Herders, too, are deeply affected. Although none spoke directly for this report, Kaka said he had witnessed the impacts. “Just like they deny us access to our lands, they rustle cattle,” he says. “There is this man, a very good friend of our neighbour, whose cattle were carted away earlier this year. He left in the morning with his herd but returned in the evening empty, devastated. He was so shaken by it. He died a few weeks ago.”

He had seen its impact on another herder. “There is also this man, displaced from Baga, whose herd consisting of over 100 cattle was rustled five years ago,” Kaka explains. “Now, he just sits under a tree in the market, staring into space. He does not speak unless agitated. If there is a quarrel nearby, he gets triggered. People pour water over his head to calm him. His children care for him.”

Responding to trauma

For years, mental health has remained a silent crisis among Nigeria’s displaced communities. HumAngle has uncovered the depth of this suffering in the past, especially among children.

Yet, the problem continues, often unspoken.

Kaka lies awake most nights, his thoughts heavy with worry. He often goes two nights without sleep, haunted by the fear of not being able to feed his family. “Just last week, I did not sleep for two nights,” he says. “I am exhausted after a day’s labour, but I cannot sleep because I keep thinking about providing for my family.”

“Everyone responds to traumatic events or stress differently; individuals might experience the same problem, but the way they react would be different,” says Asmau Mohammed Chubado Dahiru, a Consultant Psychiatrist at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in Maiduguri. She has witnessed these patterns firsthand. “Being displaced [itself] can be depressing,” she explains. When people go through traumatic experiences without receiving help, “they come down with conditions like social isolation, difficulties in sleeping, and difficulties in functioning.” These symptoms, she adds, gradually accumulate and can lead to “full-blown mental health disorders.” Among the most common in the region, she lists depression, anxiety, and insomnia. But very few ever receive a diagnosis, and fewer still receive care.

Kaka constantly fears for his safety and that of his family. “The constant fear alone, especially while on the field, is enough to keep you worried,” he says. “There was a time during harvest, they [terrroists] chased us away. We ran and left our beans.”

Yusuf shares similar fears. “When we are on the shores, we are always anxious, always in fear,” he says. “We may be attacked by the terrorists or mistaken for them by the military. We are not safe in the town either. We are constantly worried. For me, the hunger and fear keep me awake through most of the night. There is no peace of mind.”

He adds, “Some of my friends, who had experienced some form of attack on the shores or those of us who witnessed the massacre 14 years ago, get agitated by the slightest commotion.”

Kaka also worries about his health, especially the possibility of developing hypertension. “I might have already. Who knows? My heartbeat increases when I am deep in thought. It beats faster,” he says. He has seen what it has done to others. “There are two men who died in my area from hypertension,” he says.

“Excessive thinking can also lead to headaches, hypertension, etc.,” Dr Dahiru explains. “These are all interrelated with mental health. The presence of the physical challenge they have experienced can lead to a mental condition,” she adds. “Stressful events stimulate some hormones like cortisol, and this usually affects mental wellbeing. Depression and other conditions are a result of neurotransmitter imbalance. This, in most cases, is caused by stress.”

Yusuf, too, fears what these issues might cause. He has already seen the cost. “One of our colleagues got paralysed three years ago. He died two weeks ago,” he says.

Yet, despite the mounting psychological toll, few speak openly about their pain. In many communities across the region, suffering is endured quietly, masked by cultural expectations of strength and resilience. Mental health remains shrouded in silence, viewed by some as weakness, by others as a spiritual problem best left to clerics or traditional healers. The result is a landscape not just of displaced people, but of invisible battles waged alone. What lies ahead is not just a crisis of care, but one of recognition.

Struggling in silence

Mental health is an unfamiliar concept in many displacement-affected communities across the region. The silence around it is not merely cultural; it is also structural. Across displacement camps and rural settlements, few understand what mental health means, fewer have access to care, and stigma continues to cloud the little awareness that exists.

One in five people in conflict-affected zones may experience a mental disorder, according to the World Health Organisation. In sub-Saharan Africa, research has shown that PTSD prevalence ranges from 12 per cent to 88 per cent, with many studies reporting rates exceeding 50 per cent, according to the Joint Data Centre on Forced Displacement. The WHO also estimates that in 2017, 20 per cent of Nigerians, or around 40 million people, were affected by mental illness.

Dr Dahiru explains that there is a serious gap in awareness. “Because of little manpower, especially in the field of mental health, and the non-functioning of some primary healthcare centres, most cases are missed,” she says. As a result, not many people, like Kaka, are aware of their conditions or where to seek help. “The few specialist centres and the tertiary centre are overstretched, not able to meet the needs of everyone at a time,” she noted.

A study by the Silver Lining for the Needy Initiative (SLNI) also shows that stigma surrounding mental health remains widespread, further hindering access to care. Nigeria also faces a shortage of mental health professionals and facilities. Among outpatient services, WHO reports that schizophrenia (52 per cent) and mood disorders (31 per cent) are the most common diagnoses. Yet, the report suggests that less than 20 per cent of these facilities offer specific psychosocial interventions.

Even where services exist, accessing them is another challenge. “Another challenge is the cost of transportation,” Dr Dahiru says. “Some people cannot afford the cost of transportation from their home to the hospital. For others, it is the consulting or even medication fees they cannot afford.”

But perhaps the biggest barrier is stigma. “Many people are unwilling to admit they have mental health conditions or even seek help,” she adds, “because society superstitiously believes anyone seeking psychological or psychiatric help is not normal. This results from ignorance.”

This ignorance often feeds into cultural and religious misconceptions. “One major challenge we have in this region is that people believe mental conditions are spiritual,” she continues. “So, instead of seeking professional help, they would rather seek divine and spiritual help. This is, unfortunately, even encouraged by some supposedly trained professionals, who are aware of the situations.”

Kaka is one of those caught in this gap. When asked if he had ever spoken to someone about what he was going through, he replied, “I have never consulted anyone.” He paused, then added, “Other than you and Kyari, nobody else knows what I am going through.”

To Kaka, mental health is not just misunderstood; it is alien. He has never heard of it, does not know what it is, and has no idea how it might be treated. When asked if anyone had ever spoken to him about the state of his mind, thoughts, or emotional responses, he said, “No.” What he had heard, however, was a distorted version: “The NGOs catch people with mental conditions in the camp. My friends say that they inject them in the head, where they said the problem is,” he recounts.

Yusuf, too, had never considered mental health as something that might relate to him. When asked what he thought about seeing a psychologist, he chuckled. “I am not mad,” he said. “Nothing is wrong with my brain.” He did note, however, that there is a primary healthcare centre in the community where they go for general health needs, but not for the mind.

Not just victims, but survivors

Amid the wreckage, some refuse to be defined by what they have lost. In the face of climate shocks and insurgency, many in the region are quietly building resilience, drawing strength from faith, kinship, and the stubborn will to continue.

“We discuss some of our problems when we sit in front of our homes in the evenings,” Yusuf says. “We get to relieve ourselves.”

For Kaka, that relief sometimes comes from visiting his friend, Kyari. More often, however, it is from chewing kolanut or sniffing snuff. “The snuff is the most effective,” he says. “It is cheap and it lets you forget your worries for a while. Goro [kolanut] is also cheap and has a refreshing taste. I cannot go a day without chewing it or sniffing snuff.”

“In order to tackle their problems, many men externalise. They discuss [them] with friends,” the psychiatrist said. “This serves as a form of support. Having some form of support helps some people.” Other men like Kaka, however, turn to substances, like snuff, as a form of escape.

In areas like Borno State and most parts of northern Nigeria, snuff (locally known as matala in Kanuri communities) is common among men, young and old. Research from Nigeria’s northwestern states supports this pattern. A study in Kano, for instance, found that secondary school students used tobacco products, including snuff, to cope with stress. Though it provided short-term relief, it masked deeper trauma and carried long-term health risks.

Similarly, a study focusing on internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Kaduna revealed a high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among those exposed to conflict-related trauma. The study suggested that such psychological distress could lead individuals to seek solace in substance use, including tobacco products, as a form of self-medication.

But the health consequences are far-reaching. Another study in Gusau, Zamfara State, found that chronic snuff users showed signs of liver and kidney damage. Snuff contains nicotine, a highly addictive substance that can lead to dependency and worsen physical and mental health over time.

Not all victims turn to substance, however. Some men become violent, taking it out on their spouses. This, however, depends on previous exposures, Dr Dahiru says. “Individuals who grew up in abusive homes tend to be abusers themselves. Violence becomes their outlet. But this is a negative coping mechanism.”

In more extreme cases, the consequences can be fatal. Some men attempt suicide, just as Kaka once considered. “[When there is] the presence of a mental health disorder, there is an increased chance of victims harming themselves or attempting suicide, especially if they have epilepsy,” Dr Dahiru says.

“Sometimes, the extent of the mental health challenge, like depression, when there is rational thinking loss, victims may want to kill themselves. However, depression is more common in females than in males,” she observed. “The difference, however, is that when it occurs in men, it gets to an extent where rational thinking is lost, making them think of suicide and kill their family as well. This is the extreme of it.”

In 2019, a man was found hanging at the government house in Maiduguri. No one knew exactly why he did it, but his colleagues noted he had been unusually withdrawn in the days leading up to his death.

The mind needs healing too

While humanitarian efforts in the region often focus on food, shelter, and physical security, a quieter crisis festers, one that bags of rice and makeshift tents cannot fix. Across communities battered by insurgency and climate shocks, people carry wounds that are not visible: grief, fear, trauma, and a loss of self.

“As long as we are alive, we will continue to survive,” Kaka says quietly. Yet survival, for many, has come at a steep mental cost.

Like others in his community, Yusuf hopes the government will support their recovery not just with food or shelter, but with the means to rebuild their livelihoods. “The rainy season is fast approaching. Farming is the only sustainable thing at the moment. We would like the government to provide farming aids,” he says.

But even as families prepare to plant seeds again, healing the land alone will not be enough. The mind, too, needs tending.

Organisations like the World Health Organisation and the International Organisation for Migration have taken steps to address this gap. According to Dr Dahiru, they have trained and deployed community volunteers to educate people in both host communities and IDP camps about mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS), teaching them how to recognise when something is wrong, how to cope, and where to seek help. “People are coming forward,” she says. “But there’s still a long way to go.”

To truly make a difference, Dr Dahiru adds, more must be done. “We need more awareness, more advocacy. People should be sensitised about healthy coping mechanisms and educated about the dangers of substance abuse. The government must also recognise that mental health is as important as physical health. Care should be accessible, affordable—if not free.”

Because without healing the mind, recovery remains incomplete.

Kaka Ali, a displaced farmer in Nigeria's North East, struggled with thoughts of suicide due to mounting debts and hunger, reflecting a wider mental health crisis exacerbated by conflict and environmental challenges in the region. Farmers, fishers, and herders face not only economic hardships but also psychological distress caused by climate change and extremist threats, with little mental health support available. Mental disorders, including depression and PTSD, are prevalent due to stress from displacement and violence, yet stigma, lack of awareness, and limited resources hinder access to care. While organizations are beginning to address mental health needs, more comprehensive efforts, including awareness and affordable care, are crucial for complete recovery and rebuilding lives.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter