Civilians Bear the Brunt of Military Air Raid on Lakurawa Terrorists in Nigeria

With over $1.8 billion in military spending over the last decade, civilians continue to bear the brunt of Nigeria’s military misfired air strikes targeting terrorists in the northwestern region.

Ibrahim Aliyu, 40, is still torn between a mix of anger and disbelief as he stands at the entrance of his charred hut, looking pale and quiet. He had a dried tear streak as his reddened eyes scurried between the debris and the huge crater in front of the hut. In a corner, where he had once stored his family’s harvest, were blackened sacks of millet littering the ashy floor. Ibrahim took a step into the room and pointed at his wife’s burnt iron bed frame, but before he could say a word, a fresh wave of tears streamed down his face.

“That was her room,” Ibrahim muttered. “Mantu, that’s her name.”

In the early hours of Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, Mantu woke up to perform her ablution and observe morning prayers when she saw a fighter jet hovering over the area. At first, she was unbothered, and like other residents of the Gidan Bisa area of Silame, Sokoto, North West Nigeria, she glanced at the jet and beamed softly as it passed over the village. The fighter jet was providing air support for the ground troops to expel the Lakurawa terror group from the country. The village lies just a stone’s throw from the Surame Forest, a known hideout for the terror group.

The sight of the fighter jet gave the villagers a shot at hope that the security of their lives and property was being given the deserved attention. Mantu was about to enter her room when an earth-shattering sound enveloped the area, followed by a thick dust that swirled around the village before the explosion that eventually felled her at the entrance of the hut. Mantu clutched onto the wood that held the door, signalling to whoever cared that her five children were stuck inside as she fought the fire. But no help came. The fighter jet dropped another bomb. And another.

Later that day, Abdullahi Abubakar, the spokesperson of the Joint Task Force Operation Fansan Yamma, which conducted the strike, said those that were killed “have been positively identified as associated with the Lakurawa group”, dismissing that the air raids hit civilian settlements.

Meanwhile, Major-General Edward Buba, the Nigerian Army spokesperson, confirmed the incident but attributed the death of civilians to secondary explosions. He explained that the strike on the terrorists’ logistics and arms cache led to the explosion, causing hoarded munitions to explode in different directions.

Ten civilians, including Mantu and her five children, were killed and 14 others injured. HumAngle visited the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, where the lives of four of the injured victims are currently hanging by a thread.

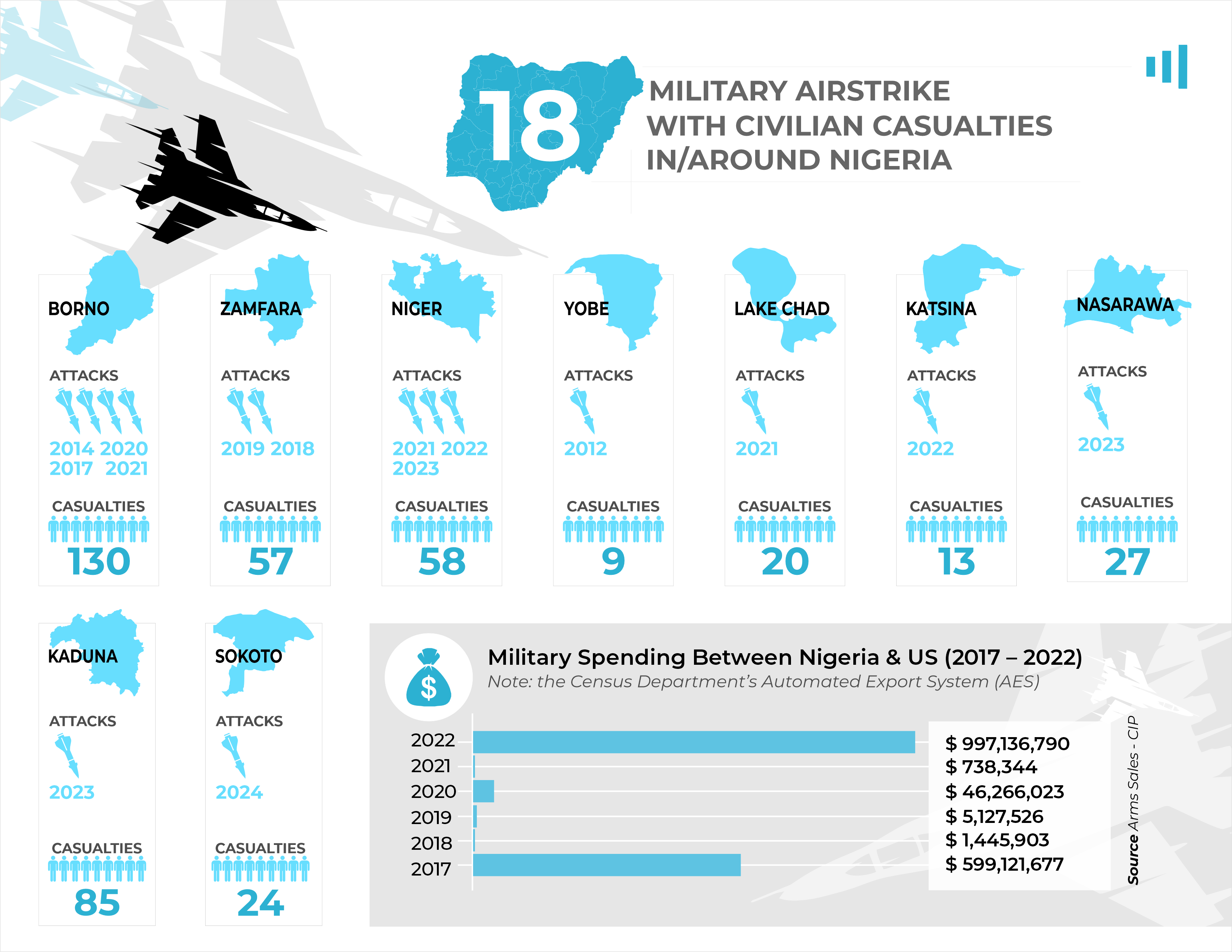

This is not the first time military air raids targeting terrorists have struck civilian settlements. At least 18 similar incidents have occurred, resulting in the deaths of over 400 civilians and injuries to hundreds more, in clear violation of humanitarian laws that mandate minimal harm to civilians during conflict. Yet, the military rarely acknowledges these casualties and often deflects responsibility, like this one.

In the few instances where responsibility has been admitted, such as the Tundun Biri incident in Kaduna, there has been little follow-up regarding support for victims or measures to prevent future tragedies.

Ibrahim, Mantu’s husband, was in Gande, a neighbouring village, where he had gone three months earlier to work as a porter with his camel. He said he was preparing to head out for his daily routine when his brother Chika called to inform him about the incident.

“I got home to see my wife and five children completely burnt. It’s a sore sight. No lives should ever be lost like that,” Ibrahim said amid sobs. He walked towards a small hut, nudging his head in response to greetings from sympathisers who had come to condole with the village. He entered the small hut, brought out a threadbare raffia mat, and spread it under a tree, a few walks from the hut. It was one of the few possessions left that he could lay his hands on.

“I never expected to come back and see my family in such a situation,” Ibrahim suddenly welled up. The father of nine said he returned home briefly a week before the incident, and “they (the children) were following me around. I even gave them bread, but they wouldn’t leave me” because they had missed him. He had to give them ₦500 before they finally went back to their mother. “I returned to Gande, expecting to see my family again, not knowing it would be the last time I’d see them,” he snorted.

A deadly pattern

The northwestern region has been a stronghold for terror groups for over a decade now. The terrorists have relentlessly attacked and raided rural villages across the region. They impose levies on communities and force residents to work on farmlands confiscated from them. More than 20,000 people have been killed, and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes in what started as a face-off between farmers and herders over scarce resources, amongst other factors. Recently, the Lakurawa terror group, once called harmless herders, joined the fray, posing an even graver threat in the troubled region.

Authorities recently launched a renewed offensive, code-named Operation Fansan Yamma, to invade terrorists’ hideouts in the North West. Other measures have also been rolled out, including the presidential directives requesting the service chiefs to relocate to the region for proper operations coordination.

The situation is not any different in the North East, where jihadi groups have held sway for years, prompting the Nigerian government to inject millions of dollars in budgetary allocations to support the military in its efforts toward ridding the country of terrorism.

Within the last decade, foreign military sales between the U.S. government and Nigeria have amounted to $1.8 billion, in addition to $650 million in security aid, cementing the U.S. as Nigeria’s key strategic partner. In 2021, Nigeria received 12 Super Tucano warplanes as part of a $593 million package approved three years earlier. The following April, the U.S. approved nearly $1 billion in arms deals, leading to the purchase of 12 AH-1Z attack helicopters and supporting munitions, despite concerns raised by American lawmakers regarding possible human rights violations.

Other military hardware and equipment purchased within the same period include aircraft, bombs, rockets, and mines. The Nigerian government has also heavily invested in procuring laser, imaging, and guidance equipment, unmanned aircraft, military vehicles, and tanks, as well as funding training and capacity development. In 2021, for instance, Nigeria spent $177 million on aircraft and supporting munitions, 12 military fighter aircraft, guns, dynamites, and ground vehicles in direct commercial sales by U.S. companies. Data shows that between 2018 and 2022, the U.S. government licensed the sales of defence articles valued at $53 million to Nigeria via direct commercial sales (DCS).

In the proposed 2025 budget submitted by Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu, defence took the lion’s share of ₦47.90 trillion. While the Defence Headquarters wants to spend about ₦2 billion on procuring arms and ammunition, the Nigerian Army earmarked ₦110 billion for defence equipment, including ₦19 billion on unmanned aerial systems with additional ground stations. The Airforce intends to spend ₦70 billion on defence equipment. The boost in military firepower has helped to decimate terrorist strongholds, especially in the Northeast. Unfortunately, it has also put civilians at greater risk — a situation analysts attribute to Nigeria’s longstanding security sector governance challenges.

The fact that ‘accidental’ airstrikes have resulted in civilian casualties on “too many occasions show that something is wrong with our counterinsurgency approaches, especially when it comes to the deployment of technology, such as drones or fighter jets,” Samuel Malik, a Senior Researcher at Pan-African think tank Good Governance Africa, told HumAngle.

“Based on how recurring the incidents have become, it seems the military doesn’t care about proportionality. When the likely harm to civilians outweighs the expected military gain, such attack should be reconsidered, but in Nigeria, it appears that the military does not bother about proportionality,” he added.

The villagers killed by military air raiders fighting the Lakuwara terrorists are the latest victims of recurring airstrikes.

Bube Danladi, 30, for instance, returned to Gidan Bisa about two months ago to prepare for his wedding. Fresh from his Islamiyya studies in the Kura town of Silame, his room was filled with carefully curated Islamic texts he had brought with him. These texts were meant to be a stepping stone toward his ambition of becoming a scholar until the fighter jet attacked the village and turned everything, including him, to ashes.

That morning, as Bube stood at the doorway, preparing to leave his room, the military struck and caught him in the neck.

“What haunts me most are the everyday moments; how he’d spring to action whenever I needed help, insisting I rest while he took on my tasks. His respect and care shown in these small gestures made his absence feel deeper with each passing day,” said Magaji Danladi, Bube’s father and the community village head.

Back in his little hut, Bube’s father is still stricken with fear. At every given opportunity, he would exonerate the village of wrongdoings.

“Do we resemble Lakurawa?” Danladi exclaimed. “We have been here for generations, but they came and opened fire on us just like that. With my own eyes, I have never seen Lakurawa. But they came and killed people here. They killed my Bube; They killed him.”

Shooting spree

On Dec. 26, 2024, a day after the strike, the air over the villages of Gidan Bisa and Rumtuwa hung thick with grief and despair as villagers nursed the stings inflicted by Operation Fansan Yamma forces. Four military vehicles stood sentinel at the village entrance, while others entered the village to conduct an impact assessment of the destruction they had caused just hours before.

The soldiers moved through the ruins with cameras and notes, documenting the aftermath. While the shutters capturing the ruins wrecked on the village were as clear as a whistle, the villagers could only watch silently, some murmuring, others feeling helpless.

The same men had come to open fire on them after the fighter jet whirred off in the smoky air. Residents told HumAngle that the ground forces descended immediately, blocking local rescuers from assisting the villagers and preventing them from gaining access to the area in an apparent sweeping operation.

In the dirt paths between damaged homes and dead livestock, HumAngle found spent bullet casings that corroborated the residents’ accounts. Three locals sustained gunshot injuries. At Usmanu Danfodiyo Teaching Hospital in Sokoto, where the survivors are being treated, many are still in critical condition and can barely lift a finger.

“As we ran into the bush for cover, the military arrived and opened fire everywhere,” the village head recalled. “The neighbouring communities coming to help were chased out by the military. In the process of chasing people out, they shot three people among those who came to help.”

The clear disregard for civilians’ lives has consequences, Malik warned, noting that human rights abuses by government forces “present one of the easiest recruitment opportunities for terror organisations, especially in the Northeast and the Northwest. Terrorists have used legitimate grievances communities have against the military to recruit fighters”.

A father’s last rite

Bello Danladi saw to his family’s safety until his last breath.

Over in Rumtuwa village, located among a rise of rocky terrain in the Silame area, the morning was still cold. Fatima Bello, 25, stood outside her family’s hut to perform ablution for her morning prayer. She was still praying when her husband, Bello, busted in following the earth-shattering noise from the neighbouring Gidan Bisa. They knew something was wrong but didn’t quite get the full grasp. The fighter jet pierced into the dawn silence and rained fire on the hamlet.

“My prayer was rushed and scattered,” she said. “I barely remember completing it when my husband rushed in to fetch us.”

As they gathered nearby, watching stealthily as their village was being reduced to rubble, Bello noticed that her youngest daughter, Aisha, was missing. “When I told him she was still sleeping inside, he quickly gathered our youngest in his arms and urged me to fetch Aisha. I hurried back into the house with my heart pounding.”

When Fatima returned with Aisha, Bello gently held her hijab, drawing his entire family of six close to himself, like a shepherd looking after his herds, and took them out of harm’s way. But then, he looked back at the house; there were cows and other livestock. Bello told Fatima to go on with the kids and went back, “I clutched his arm, trying to hold him back. “Please,” Fatima begged. “Leave it.” But Bello was a man who cared for all under his protection. He gently pulled away, promising to return quickly.

That was the last time she saw her husband. The jet’s missile found his home just as he reached the cows. The explosion burnt him to death. There’s nothing left of him. “When we came back, we didn’t even see his body as the fire burnt him into ashes,” Fatima broke down in tears. Now left with five daughters, one soon to be married, the future stretched before her like an empty road. No food in the store. No father to guide them.

Danladi’s final act was one rooted in his strong conviction to protect all that was under him, including his sheep. Caring for what’s his to protect. Now that he is no more, Fatima could only carry him in her heavy and scarred heart. “He has done everything for me during his life as he provided all l needed. I will never forget him in my life because he has been very kind and supportive to us,” she said, praying for her husband.

A tragic airstrike on Christmas Day 2024 targeted civilians in the Gidan Bisa and Rumtuwa areas of Silame, Nigeria, leaving ten people dead, including Mantu and her six children. The military claimed the operation aimed at the Lakurawa terror group, denying civilian targets were hit.

However, the incident is part of a pattern where over 400 civilians have died in military attempts to counter terrorism, often without responsibility acknowledged by the military.

The northwestern region of Nigeria faces ongoing violence from terror groups like Lakurawa, resulting in thousands of deaths and widespread displacement.

The military's response, supported by significant defense spending and international arms deals, has inadvertently caused civilian casualties due to governance challenges in the security sector. Analysts have expressed concerns that such actions undermine local trust and inadvertently aid terrorist recruitment efforts.

In Gidan Bisa and Rumtuwa, survivors recounted further violence from ground military forces following the airstrike, which obstructed rescue operations and resulted in additional injuries. The repeated airstrikes and ground assaults reflect a dire need to reassess counterinsurgency tactics to prevent such tragedies.

The personal stories of loss, like that of Bello Danladi, highlight the human toll and the challenge facing communities already vulnerable to terror attacks.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter