Children of War, Fathers of Regret

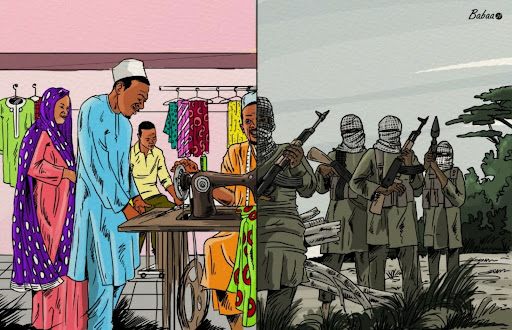

They once carried guns and filled their homes with the language of violence. Now, as “repentant fighters” living in normal society, some carry the weight of regret, the sting of stigma, and the fear that their children may inherit their scars.

On a dusty morning in Nigeria’s northeast, the echoes in camps are no longer the rattle of gunfire or the rumble of motorcycles but the piercing laughter of children. They pour out of makeshift classrooms, books tucked under their arms, chasing one another through narrow lanes of zinc and tarpaulin. For many, school is not just about education but an escape, a first glimpse of a world where survival is not the only lesson.

Among them are the sons and daughters of men who once believed learning was a path to hell and that the surest road to paradise was to kill or be killed by ‘non-believers.’ Their fathers carried rifles under the black banners of Boko Haram, preaching that martyrdom was salvation.

Boko Haram, Nigeria’s deadliest insurgent group, launched a brutal campaign of bombings, kidnappings, and massacres in 2009 to establish a hardline Islamist state. Its splinter faction, ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province), emerged in 2016 under the Islamic State (IS) banner, proving more strategic and deadly by targeting security forces and expanding across the Lake Chad Basin.

Today, some of those same men who went forth to champion the Boko Haram and ISWAP doctrines are learning how to teach something far more delicate to their wards – peace as their only means of survival after abandoning the bush and settling in normal society.

The burden of memory

Baba Kawu sits cross-legged outside his shelter, his youngest child nestled in his lap. At 28, he looks worn beyond his years, his face mapped by exhaustion and survival. He remembers the sermons he once delivered at home and in his neighbourhood about violence against anyone who disagrees with the group’s corrosive doctrine.

“I made my children accept,” he says. “They studied our doctrine, and they prayed for us whenever we left for battle.”

His children grew up where war dictated bedtime and dawn alike. Their lullabies were not fairy tales but fiery exhortations. Now, his tone has shifted: “I tell them to be patient, to live peacefully even when others mock them. Everything passes. History will judge.”

Kawu’s regret is stripped of confession; he does not dwell on lives taken or the violence spread. His sorrow is personal — about years lost and paths not walked. Yet in this fragile second life, he clings fiercely to the hope that his children will chart a gentler future.

A childhood in the bush

For Muhammad Mustafa, the shift is even sharper. He joined Abubakar Shekau’s faction of Boko Haram at 25, took a wife in the bush, and raised five children under the grip of the insurgency they conducted.

“They supported me,” he recalls with a shrug. “Everyone in the Daulah supported the cause. My children prayed for us before we marched.”

When Mustafa surrendered, his eldest child was 11, and the youngest was still a toddler. None had fought, but each inhaled the ideology saturating their world. Their memories are of armed men, whispered warnings and endless movement to escape bombardments.

Now, Mustafa is practising another kind of fatherhood. His children go to school in Maiduguri. He tells them to avoid trouble and to carry themselves with dignity.

The counselling sessions offered by officials and civil society groups helped him find his footing, though he insists his heart carries no guilt. “I only regret the wasted years in the bush,” he says. “Life is more peaceful here,” he adds.

According to Mustafa, in 2007, when Muhammad Yusuf, the late founder of Boko Haram, was preaching and recruiting young people, he was among those who stood with opposing clerics who believed Western education is not bad as long as it is complemented with Islamic education. “But later, as more and more of my friends joined the Boko Haram-led insurgency, I also joined in October 2013.”

Today, four of his five children are in public schools, and when they close in the afternoon, they attend Islamic school, learning about Islam.

“I have returned to my initial belief after wasting 12 years during which I killed scores of people whose only crime was disagreeing with the doctrine propagated by Boko Haram.”

The commander’s contradiction

Ibrahim Abatcha, known as Abu Zara, once commanded more than 80 fighters. His authority was unquestioned; his voice was law in forest settlements under Shekau and later ISWAP. He was both preacher and warrior, teaching his wives and children the same dogma he enforced at gunpoint.

“They saw everything,” he said in a heavy voice. “It was the general belief in Daulah. Everyone supported me.”

His children were too young to fight but old enough to watch, listen, and absorb. They clung to his words, cheered when he left for war, and prayed for his safe return.

Today, he sets different rules: live simply, stay out of trouble. His wives tell stories of defectors rebuilding lives. They weave new bedtime tales, replacing jihad with promises of school, farming, and business.

“I only regret my years in the bush,” he admits. “I don’t regret my decision to walk away.”

Fathers at a crossroads

What binds Baba Kawu, Mohammad Mustafa, and Ibrahim Abatcha is the uneasy balance between past and present. Once warriors and leaders, they now stumble through the uncertain path of fatherhood. Their children once prayed for victory in battle; today, they clutch slates and notebooks in Maiduguri. Their mothers, who once reinforced extremist violent ideas, now push for patience and classroom, the deradicalisation programme at which NGOs and state counsellors teach the language of coexistence.

Yet a contradiction lingers. These men once belonged to a movement that weaponised children. Now, they must raise their own under the gaze of a state desperate to break that cycle.

HumAngle probed them further by asking whether there is a slim chance that they may slip back into violence. All three insisted that they prefer their current life for their children. However, Abatcha said if not for his children, he would have returned to the bush because of broken promises.

“The government never delivered on most of the promises it made to us,” he said, referring to the promises made to coerce them to lay down their arms and surrender. “Now, we live on handouts.” He still awaits a lump sum from the government to start a business after surrendering with dozens of fighters with their AK-47 rifles.

Broken promises in Borno

Maiduguri, the birthplace of Nigeria’s insurgency and the laboratory for its undoing, has absorbed wave after wave of displaced civilians and defectors. The government promised deradicalisation, rehabilitation, and reintegration. In practice, funds are thin, accountability scarce, and programmes patchy.

In camps meant to reshape fighters into civilians, hunger and stigma settle more deeply than hope. Clients –as the defectors are called– say that counselling is irregular, skills training unreliable, and reintegration plans more rhetoric than reality. Families wait for promises that rarely arrive. Hope expires quickly here.

Many people do not regret abandoning a life in which they were expected to live or die each day. Most only regret their inability to reintegrate due to a lack of funds and the stigma they face. “Only those with relatives who are willing to assist them are now doing well,” one defector mentioned.

Vanishing defectors

The cracks are widening. Many defectors no longer report to the state. Instead, they vanish into towns across Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Without paperwork or follow-up, they slip into slums, markets, and borderlands, unmonitored and unaccounted for.

Two defectors (names withheld) who are now living in Kano and Kaduna, respectively, said they sold their belongings, such as livestock, motorcycles, firearms, and everything they had acquired over the years from fish trade, extortions, etc., and escaped to Jigawa from the Lake Chad Basin.

It was in Jigawa that the two partners in crime decided to reach out to friends who had defected earlier, and the decision to settle in two separate cities was made.

“We wouldn’t have made it if we had no money,” they said.

HumAngle learned that many of the fighters who surrendered to the authorities are those who have no resources to resettle on their own. The ones who have the means to settle down on their own sneak into communities and major cities, without any de-radicalisation efforts for them to contemplate leaving extremist tendencies behind.

What happens to them, and more urgently, to their children? Without structure, silence replaces ideology, creating a void that may not secure peace but prolong uncertainty.

Brotherhoods in the cities

In Kano, Abuja, Kaduna, and Lagos, informal brotherhoods of former fighters are taking shape. Once bound by war, they now rally around survival. They share food, contacts, job opportunities, and the faint echo of belonging, where the state has failed to provide.

This fraternity thrives across West and Central Africa, sustained by weak institutions that are unable to track citizens’ identities or movements.

In Maiduguri, one can commit a crime and simply reappear in Lagos or Abuja, shielded not by law enforcement’s vigilance but by its absence. The real threat comes not from the police but from victims who might one day recognise such persons and alert local authorities.

Among these terrorists and armed fighters lie two stark truths: their resilience in seeking to rebuild lives beyond violence and the lurking danger that dormant loyalties may smoulder, ready to ignite when uncertainty offers cover.

The quiet fear

When asked if their children still cling to old doctrines, all three men answer firmly: no. They pointed to classrooms, new routines, and neighbours who are slowly accepting them.

But their insistence is based more on hope than certainty. They celebrate their children’s adjustment but avoid the deeper question: what remains of a child raised in war, even if only for their earliest years? The answer lies decades ahead.

One of the fighters recounted how his child began to share stories of war with the children of their neighbours, and his mother had to intervene quickly, “otherwise we would have been exposed.”

They now shield their children from others in the meantime as they try to settle into their new life in Kaduna.

Another former fighter said the sound of planes always rattles his children seven months after leaving the forest in southern Borno. “My family thinks it is the sound of fighter jets,” he said.

Legacies of insurgency

For now, the deradicalisation camp in Maiduguri is both refuge and cage–a place safe enough to shelter them, yet too fragile to anchor their future. Fathers dream of farmlands, schools, and trade. They imagine children free from stigma and the trauma that both parents and children alike endure daily.

Nigeria’s frontline is no longer Sambisa’s forests but the homes of men like Kawu, Mustafa, and Abatcha in Maiduguri — and in towns across West and Central Africa. The real battle now plays out in conversations between fathers and their families, as they struggle to replace the legacy of violence with the hope of peace.

In northeastern Nigeria, once-terrorists who followed Boko Haram and ISWAP are now transitioning to civilian life, focusing on peace and education for their children.

After years of conflict, former fighters like Baba Kawu, Muhammad Mustafa, and Ibrahim Abatcha grapple with their past deeds and aim to guide their children away from violence, although troubled by broken promises from the government regarding reintegration.

As former fighters attempt to reintegrate, they face unreliable support systems, relying instead on informal networks and battling the legacies of conflict that persist in their children’s minds. The struggle to rewrite their children's futures continues amidst societal stigma and inadequate state intervention.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter