Chased By Terrorists, Caught By The Military: Two Sides Of An Ugly War

Adam ran to the military expecting help. Instead, he was condemned and put away.

Boko Haram wanted Adam Lawan dead.

As a politician and vigilante, he represented everything they detested: allegiance to democratic rule and brazen defiance of the group’s armed insurgency. So they went after him each time they raided Uta, a village in Bama, northeastern Nigeria. But Adam was lucky to escape the attempts on his life.

The second time terrorists stormed his home one night in 2015, he was not inside. Hearing what happened and encouraged by his family, he dashed out of town with a friend and sought help from the military base in Darajamal, asking them to escort people to the safety of the capital city. He could not have expected what happened next. The soldiers insisted they themselves were suspected Boko Haram members and immediately arrested them.

Adam’s friend, Ali, was able to share what happened after his release the following year. Adam, on the other hand, remains in detention.

One reason the arrest was all the more shocking was Adam’s reputation in the area. He was ward chairman of that political party “with the sign of a broom”, says his wife, Kellu Lawan Eli, as she makes a sweeping motion with her right hand. She is referring to the All Progressives Congress (APC), a merger of three opposition parties which came to power at the federal government level only two years after its birth.

Adam, 54, was a man of many hats. As a member of the APC, he was active at the ward level and often visited other communities, such as Bama town, to mobilise people for voting. He was one of the party delegates who participated in the primaries of Dec. 2014. He was a distinguished voice and leader in the area even before his involvement in politics.

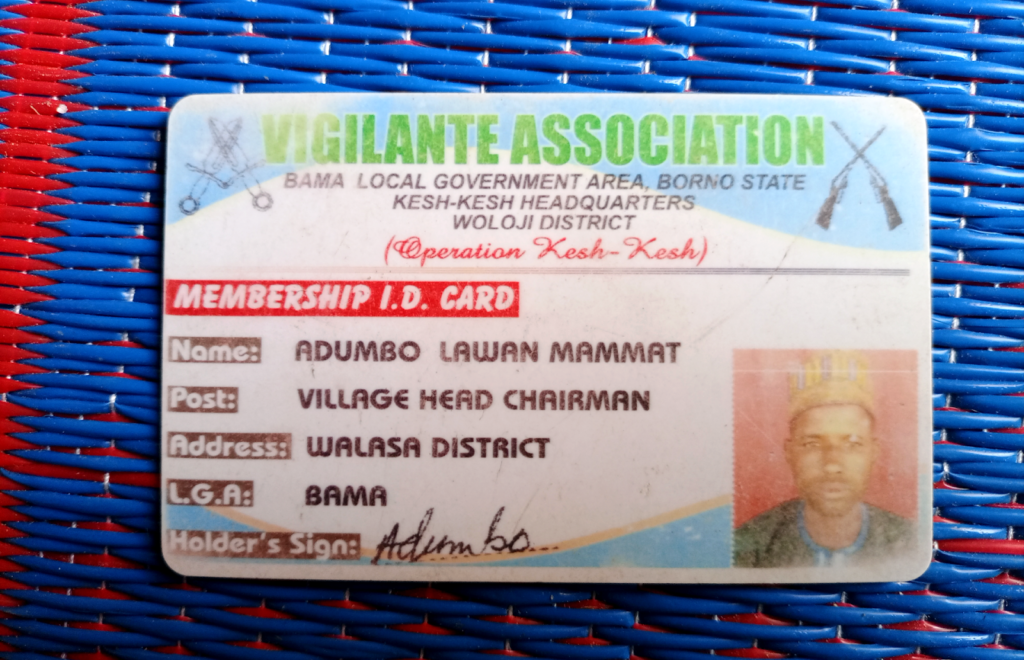

Adam was also chairman of the Kesh-Kesh, a vigilante group found in Shuwa communities. If the target on his back was initially passive, his role in the security outfit was enough to place him at the top of Boko Haram’s wanted list.

In many communities in Borno, which has been rocked by violent extremism since 2009, volunteer security outfits fill a gap left by state forces. They enjoy a wider presence and are more trusted by the locals. The Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) emerged in 2013, supporting military personnel in identifying suspected Boko Haram members and conducting joint patrols with soldiers. There are also less structured self-defence outfits like the Kesh-Kesh, vigilante groups formed in Shuwa communities.

The Kesh-Kesh’s origins have been traced back to the 1980s, which saw Nigeria plunge into a recession and then a period of increased crime. Just as they fought back thieves then, they again took up arms against Boko Haram insurgents, repelling some of the group’s terror attacks and protecting the people.

‘His life was in danger and that was why he went to the military to seek help. But they ended up arresting him.’

— Abba Lawan

Given Adam’s position, he had expected the military personnel in Darajamal to lend their support or, at least, their ears. But even after he was picked up, his wife says the military did not pay them a visit to investigate Adam’s alleged crimes or inform the family of what happened.

She only found out the reason for his absence from Ali, Adam’s companion. She had gone to visit him in Bama and he narrated how he spent nine months in detention, most of it at the notorious Giwa barracks in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital. Adam was still at the detention facility when he was released.

Ali, too, has seen the worst of both clashing sides of the war. He had gone to the forest to fetch firewood last September and was killed by Boko Haram terrorists.

In northeastern Nigeria, it is common to hear stories of people getting picked up by the military on suspicion of supporting Boko Haram — the same group that tormented and forced them out of their homes.

Another victim, Mallam Jime Ganama, 40, was arrested in 2016 after he moved to the Jiddari bus stop area of Maiduguri with his family. He was displaced from Chachiri, Bama, by the conflict and had relocated with his family. One Friday night after they had retired to bed, soldiers knocked on their door, invited Jime out, and whisked him off to the barracks. His offence? He taught women at a Qur’anic school in the village. But his wife, Kellu Quais, says Boko Haram had appointed him as a teacher and they would have killed him if he refused.

“The last I heard about him was about a year ago.”

At first, Boko Haram’s base was in Maiduguri after its emergence in 2002. The founder, Mohammed Yusuf, gave regular sermons at the Ibn Taymiyyah Mosque. But following a period of increased confrontation with law enforcement agents that climaxed with the death of Yusuf in 2009, the terror group became more brutal in its campaign. Its members camped in the Sambisa forest area and conducted attacks as far as Kogi in north-central Nigeria and Sokoto in the Northwest. At its peak, it captured and maintained control over a sizeable chunk of the Northeast, including 14 local government areas in Borno.

Before the crisis escalated, the insurgents would visit Uta during the day as they moved to other places. They would instruct the residents to adopt their lifestyle and religious codes. Sometimes, they raided at night in search of people like Adam. They never stayed for long. But that changed after the people became displaced. “When we left, they took over the village,” Kellu says.

Even the strong resolve of the Kesh-Kesh could not hold up against the insurgents’ increasingly advanced firepower.

Abba Lawan, 50, Adam’s older brother, lost five family members to the bloodbath, including an older brother, cousin, and uncle. He remembers a time when the terror group came with armoured vehicles. “They lay the vigilantes on the road and crushed them,” he says. “So we saw that this was more than our power.”

Everyone had to leave.

Abba says Boko Haram took most of their livestock and they escaped on foot, trekking for five days before finally arriving in Maiduguri. The men travelled alone because they feared the insurgents would harm them if they saw them with their wives and children, realising that they were trying to escape. Abba himself waited to be escorted by the night sky before sneaking out.

The Lawans left Uta two weeks after the terror attack. Kellu and her four children first moved to Kolofata in Cameroon, then Mubi in Adamawa, before settling in Maiduguri. She did not realise it at first but, like her husband, she had also escaped death by the whiskers. “The people who came after me said the Boko Haram fighters traced my footsteps and I was lucky they couldn’t get me,” she explains.

The mass displacement had prevented her from asking other party officials for help. Since everyone was badly shaken, she imagined there was nothing they could do.

Adam is tall and, as of the time he was arrested, ‘a bit fat’. Kellu believes it was his concern for others that pushed him into politics and civic engagement. His loud voice helped as he mobilised the people to action.

“You know he was a politician … so he considered himself wise,” she says, laughing as if to hint that she has seen the silly side of him not obvious to most people. “We are proud of him; he was good and generous to people and people liked him a lot.”

Like everyone else in Uta, Adam farmed across seasons and reared livestock. He was a hardworking man who took care of his family.

“When he was around, he did everything for us,” Kellu confirms. “But now I have to do it. I have to go gather firewood and work in people’s houses and farms to feed the family. I have become old. If it were the village, I would go to the farm and get something at the end of the season. But here, there are no farms. People have to work on other people’s farms and I can’t leave the children to go.”

When the family first arrived at the Garki Block IDP camp in Maiduguri, they didn’t receive any humanitarian aid. Later and for the next six or so years, the international NGO, Action Against Hunger, supported with donated food. They recently received aid from Save the Children, but the organisation warned that the intervention would soon be ended.

“I feel very sad about his continued detention. This is his daughter, who was breastfed at that time and she is seven years old now,” Abba says as he points in the direction of little Fanne, his voice getting louder with frustration.

“But the same people who chased us with guns, we see that they have now been released. We left the village because of them, but they have come back. Nothing happened to them. This is injustice.”

He thinks the Shuwa Arabs in detention are being discriminated against by the authorities, considering how a disproportionate number of them have not been released. About 10 people from his village are still imagined to be in military custody after many years.

“But,” he adds, “many Kanuris and Gamergus have been released, and there are many Boko Haram members among them. The Shuwa Arabs are not Boko Haram and they are releasing the real Boko Haram. So let them release our people.”

Ali, Adam’s friend, who was released much earlier, is believed to, in fact, be Kanuri. Experts think this perceived discrimination could be due to the language barrier. Kanuri was the lingua franca in the old Kanem-Bornu empire and, in the last century, has competed with Hausa as the dominant means of communication among different people. Shuwa Arabic, however, remained almost exclusively spoken by the ethnic group. While native speakers living in Maiduguri have also learnt to speak Kanuri, Hausa, and, if educated, English, many rural dwellers still speak only their native tongue.

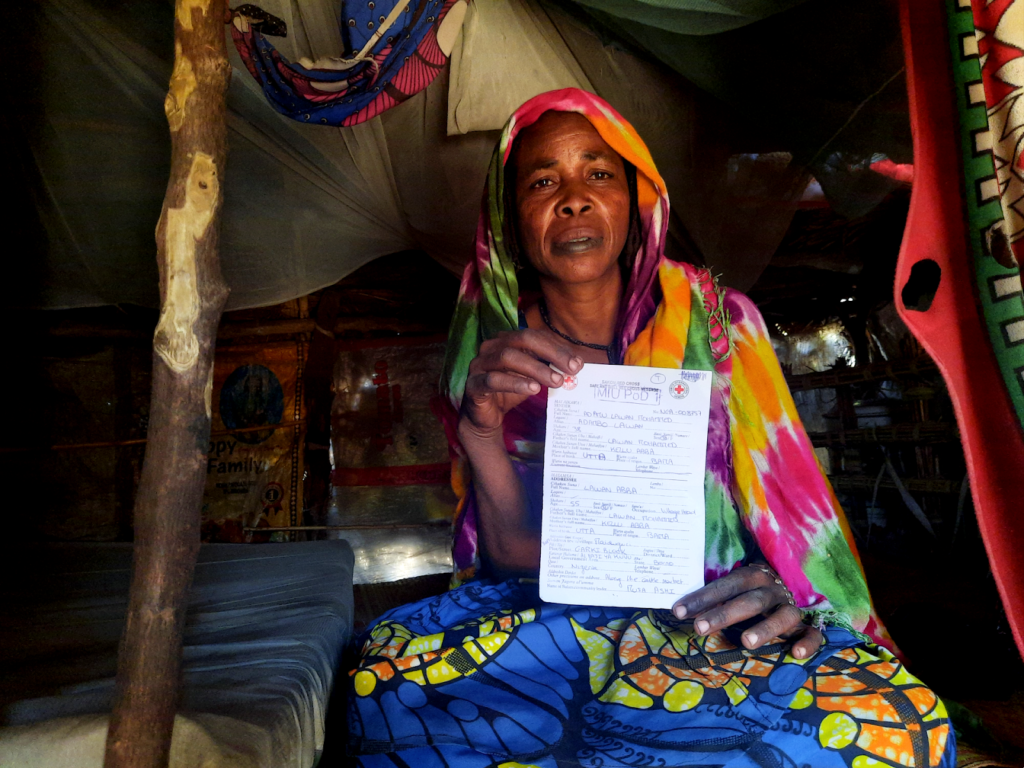

Kellu is full of smiles as she retrieves a small parcel from a rack in her room. She carefully unwraps the plastic bag to reveal a thick, shiny A4 sheet with logos of the Nigerian Red Cross and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The document has Adam’s details to confirm his identity, and is written as a letter to his brother, Abba. At the back is a general message in both Hausa and English:

Gaisuwa gareku. Ina da rai da kuma lafiya. Don Allah aika mani labarin da iyalina.

Greetings to you. I am alive and well. Please send me news about my family.

Through its restoring family links project, the ICRC reconnects separated loved ones and informs people about the status of their missing families. It hopes this will help people to cope better with the disappearance of their families. In Nigeria, the humanitarian group says it has documented over 25,000 active cases of people reported missing — the highest number across Africa.

“It was brought by Red Cross five months ago, 15 days after Eid-ul-Kabir,” Kellu, still smiling, says about the letter. “We are very happy to hear from him and hope he will come home one day.”

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter