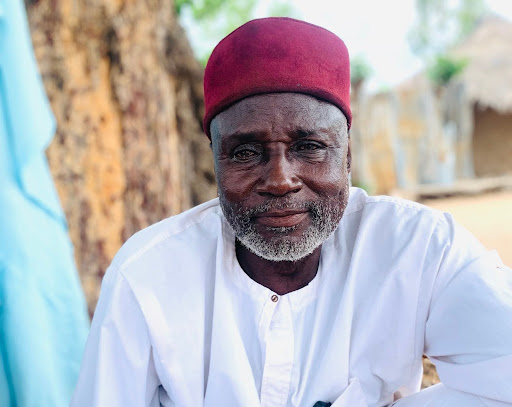

When 55-year-old Muhammad Buba, a teacher at Boshkiri Primary School, left home on July 2, family and friends had no idea they would not see him again.

On his farmland at Garin Mallam Isah, a vast land within the Lafiya district where he lived in Adamawa State in northeastern Nigeria, he was hacked with a machete by a group of armed young men and left to bleed out.

“It was a brutal incident,” Ado Mohammed, an eyewitness, told HumAngle. With repeated sighs, he recounted how he and other men had been drawn to the scene by piercing screams. When they arrived there, they saw young men fleeing with machetes in hand and Muhammad lying in a pool of his blood.

“There was a deep cut on his forehead, which caused him to bleed profusely,” Ado said. “He was also struck on different parts of his body.”

They placed Muhammad on a motorcycle and rushed back to Lafiya Town, where they tried to stop the bleeding. Realising the primary healthcare centre there could not handle the emergency, they drove him for over an hour to Numan General Hospital in the Numan Local Government Area (LGA) of the state. But shortly after arrival, Muhammad died from the severity of his injuries. His remains were taken back to Lafiya and buried that same evening according to Islamic rites.

“Muhammad was the breadwinner, and now that he is gone, I don’t know what will become of his wives and children,” Ado sighed.

Like his younger brother and many others killed on their farms in the Lafiya district, Muhammad became yet another casualty of the Waja–Lunguda conflict, now in the early days of its seventh year.

Locals told HumAngle that in recent months, bodies of both Waja and Lunguda people had been found along roadsides and farms. One such case occurred on June 16, when a body was found lying by the roadside in Lafiya town. The victim, a member of the community, died from multiple machete wounds.

Before the conflict drove them apart, the two communities shared a long history of interdependence. They used the same road networks, traded in the same markets, farmed the same land, and even intermarried.

Divided by land

The Lungunda people are predominantly based in Guyuk LGA, Adamawa State, with some residing in Boshkiri, a town in Lafiya District, which falls within Lamurde LGA, where the Waja people form a majority.

Boshkiri and Laifya towns are only minutes apart. Due to their proximity and shared cultural ties, Waja and Lunguda are often referred to as the cousin tribes.

Jonathan Alfred, the village head of Kubte, a Lunguda community affected by attacks in Lafiya District, told HumAngle that the Lunguda and Waja tribes had been coexisting for centuries.

“We [referring to both tribes] came from the same ancestral home, and then our ancestors settled in Wanda, Balanga LGA of Gombe State, before we migrated here,” the village head said. “We’ve been living together.” The communities still share a boundary with Gombe.

But things changed in 2018.

On June 9 of that year, two Waja men went to their farm in Garin Mallam Isah, a vast area cultivated by hundreds of local farmers from both communities, and never returned, Jonathan recounted. The following day, search parties found one of them dead, his body concealed beneath soya bean leaves. The other was discovered nearby, barely alive and struggling to breathe, his body marked by severe injuries.

“The one who survived was taken to the hospital, and later, he explained that they were working on the farm when a group of Lunguda people showed up and asked them to leave the land, claiming it belonged to their ancestors. They objected, and before they knew it, the confronters started beating them,” Jonathan told HumAngle.

The attack sparked outrage within the Waja community, particularly among the youth, who demanded retaliation. Within days, houses were torn down and set ablaze in the Lunguda regions of Mere, Kubte, and Mamsirme, and what began as a land dispute quickly escalated into a full-blown violent clash between the groups.

Jonathan said that the Lunguda community also retaliated, and the clashes carried on for months despite reconciliation efforts, including one initiated by Jibrilla Bindow, the then Governor of Adamawa State, who set up a committee in 2018 following the first attack. The violence only ceased with the onset of the dry season. In 2019, it sprang up around June and has recurred every farming season since.

HumAngle learnt that during these attacks, the areas that suffer the most are Kubte, Mere, Boshkiri, Zakawon, Mamsirme, and Lafiya Town itself, inhabited by both tribes. Ade Obed Feru, the village head of Mere, confirmed to HumAngle that his community has experienced attacks since then.

“I can’t even account for the properties and valuables lost,” he said, adding an unexpected conclusion to the thought: “But I’m very glad that a few lives were lost in Mere compared to other villages.”

“However, we lose houses, properties, and farms, which get set ablaze when the crisis starts every year,” he added, noting that whenever a dead body is discovered in the bush, armed youths storm his community, often at night, and randomly set homes on fire, unleashing havoc on innocent residents.

“This crisis has become a tradition, and I hate to admit that we’re getting used to it. Once planting season sets in, we don’t sleep, because people are going to start clashing over lands in the bushes out there, and then those at home will bear the brunt,” Ade said.

Residents of Mere are currently living in fear due to rising tensions, according to Ade, especially following Muhammad’s death, as every death that occurs on a farm triggers violent retaliation from the deceased’s kinsmen.

“Since security officials have been deployed and are currently on the ground, maybe we can feel safe, but we still pray that nothing happens,” he said.

A devastating pattern

According to Jacksleeve Abenetus, the village head of Mamsirme, a Lunguda community, the crisis often begins on farmlands at the outskirts before escalating into violence within the village and neighbouring communities.

“Our area, alongside Mere and other communities, suffers the most,” he said.

Even though the clashes occur in the bush, both parties come back to town and set houses ablaze in retaliation, Jacksleeve said. This implies that if a Waja native is killed on the farm, his clan members go to a Lungunda community and set it ablaze. If a Lunguda person is killed, his people go to a place dominated by Waja residents and set it ablaze.

“My community was attacked four times in the last six years, and about 56 lives were lost in total,” Jacksleeve revealed. He also said that anytime a crisis erupts and people flee their homes, the attackers vandalise properties and steal valuables.

John Mua, the youth leader of Mamsirme, told HumAngle that currently, locals who have farmlands in Garin Mallam Isah have abandoned them for the sake of their safety.

Although Mamsirme has not experienced any attacks this year, John said the community lives in constant fear, as violence could erupt at any moment, especially now that the farming season has approached.

Forty-year-old Moses Bawa, a resident of Mere, has been affected by the conflict multiple times.

“My house was burnt three times,” he said, explaining that it was first burnt in 2018. He rebuilt it, but it was burned again in the years that followed.

Moses explained that the violence has taken a heavy toll on his tailoring business, as he now barely earns enough to feed his wife and children. He initially supplemented his income with farming, but he hasn’t set foot on his farm in recent years.

“We can’t even go to our farms anymore. We are scared that people might just show up and claim the land we’ve inherited as theirs, and if we object, we might get hacked,” Moses said.

Living in fear

In 2020 alone, the conflict between the Lungundas and the Wajas displaced over 2,000 persons from their ancestral homes, according to local authorities. At least 50 lost their lives, and over 60 sustained varying degrees of injuries. Within that year, security operatives arrested 32 persons from both parties.

Since the 2018 crisis, the premises of Kubte Primary School in Lafiya have been turned into a makeshift displaced persons camp whenever the attacks happen. Mijin-Yawa Haruna, a resident of Kubte, who served as the chairperson at the camp in 2018, said the living conditions are usually terrible, as the camp is overcrowded with thousands of people.

“There are times we pile up on each other to sleep due to a lack of space. We also barely get enough aid in terms of food and other supplies,” said Mijin-Ya, adding that he hopes the current situation does not escalate and lead to displacement.

“We fear the school might close soon and open as a camp because of the recent bodies that were found. The people are scared that the attacks might start anytime, so they don’t have anywhere to go for safety except the primary school, which is always safe,” he said.

Thirty-five-year-old Aisha Abubakar’s son was shot during the clashes in 2020. He recovered but has been living in fear. “People go to the farms and hardly come back. Anytime our husbands step out, we don’t have peace until they return home in one piece. Whenever it’s farming season, we don’t get to sleep,” said Aisha.

She also explained that for fear of being attacked, she can’t access her family’s inherited farmlands around the terrain of the Lunguda people.

Aisha said she is praying for peace to be restored. “I’m tired of running around. I just want to stay home without fear of anyone coming to set my house or properties ablaze,” she told HumAngle, emphasising the mental toll the recurring violence has inflicted on her.

Gladys Eugene, the woman leader of Lafiya District, said women in the community suffer the most, particularly psychologically, during every farming season. “We’ve had cases of pregnant women who lost their babies while fleeing for safety in the past. Some even died,” she said.

Gladys, a schoolteacher at Kutbe Primary School, noted that school attendance drops every year during the farming season, as parents fear an attack could happen at any time. As a result, many prefer to keep their children at home, where they can closely monitor them. Another concern for residents is the declining functionality of the healthcare centre during this period.

Alfred explained that most primary healthcare workers are from outside the district, and many refuse to report to work during periods of crisis. During the attacks in 2018 and 2019, for instance, the clinic was completely shut down.

“We had to take care of our sick people, especially the children, the best way we could, and in terms of hygiene during that period,” he said.

If locals, who are familiar with the terrain and history of the conflict, live in constant fear, the anxiety is even more intense for outsiders.

Four months ago, Paul Zambitehile was posted to Lafiya District for the compulsory year-long National Youth Service, a programme for Nigerian university graduates. Until his posting, he resided in Benue, North Central Nigeria. Paul said he has been living on edge since reports of people being butchered surfaced, even though he has not personally witnessed any violence.

Paul and other corps members in the district are seeking relocation from the authorities.

“I heard that the violence is not a small one when it starts. That’s why I want to go, because we corps members here are not comfortable,” he said.

Homeless

On June 16, the same day a body was found lying across the street, Kubte Village was attacked in the night. Kubte is a Lunguda terrain, and the perpetrators were identified as Waja.

It was 11:00 p.m. and Dodum Gadu was asleep, with only a wrapper tied across her chest, when the violence broke out.

“Aside from the screams, there were also gunshots,” she told HumAngle. “I quickly got up and rushed to inform my neighbour that they were attacking us. He woke up, and then I went back to my house to grab a shirt, but I was in such a hurry that I ended up grabbing a scarf instead. I covered my shoulders and ran for safety with other community members.”

Shortly after, someone came to announce that her house was on fire. When people rushed to the scene, they discovered that the thatched roof had collapsed into the house and was burning.

“There was no water nearby, and the room was already gone by the time they reached, so that was how I lost my belongings and foodstuffs in the room. My sister, who had come to stay with me for a while, also lost all the things she brought in the fire,” said Dodum.

She is currently squatting with a relative, along with a few others from the neighbourhood.

Dodum pointed to the white cotton shirt she was wearing. “I don’t have anything right now apart from the wrapper I ran with. Someone gave me this shirt, but I’m glad to be alive, and my baby is fine, too,” she said.

She remains hopeful that with time, she will rebuild her house, but for now, she wants to focus on staying healthy and strong.

‘We are tired’

Over the years, the government, traditional rulers from both communities, security operatives, and other peacebuilders have come together to investigate the incidents and proffer solutions, but these initiatives have yielded little or no fruit as a new crisis breaks out every year.

In 2020, Ahmadu Fintiri, Governor of Adamawa State, set up a panel to investigate the recurring conflict between the two communities. Meetings were held and recommendations drawn, one of which was that no one from either side should cultivate Garin Mallam Isah until all issues had been resolved. However, some individuals defied the directive and returned to the land. Several of them were later attacked and killed.

Some locals believe that Muhammad Buba would have still been alive if he hadn’t gone to cultivate his farm at Duwo, which is close to Garin Mallam Isah.

Farmers like 65-year-old Hamman Jaga, a Waja indigene who resides in Lafiya town, have since abandoned the farm he inherited from his father. “My ancestors have been using the land for ages, then it was passed down to my father, and then he passed it to me. When the attacks began, we were warned never to set foot on the land,” he said.

Since abandoning the land in 2018, Hamman only returned last month, a move he blames on hunger and the poor economy. He said the quality of his life as a full-time farmer has reduced drastically since the crisis began. Feeding, he said, is hard.

“Upon reaching my farm, I discovered that my land was cultivated and soya beans were planted all over. I think the person who did it was trying to pass a message to me, and I knew if I dared uproot the crops, I might be faced with a brutal retaliation, so I abandoned it, and I don’t think I’ll ever go back,” said Hamman.

He has also warned his children to stay off the land.

Locals who spoke to HumAngle said that the peacebuilding meetings and the establishment of committees are tiring. “We are tired, and I think the security officials are even tired of us. At this point, they have left everything in our hands; if we like, we should kill ourselves,” Hamman said.

During a peace meeting on July 4 in Lafiya town, Isamaila Murray, representing the Hama Bachama, the traditional council for Lamurde and Numan LGAs, urged both communities to forgive past grievances and renounce violence.

Hamman claimed that young people on both sides are the main perpetrators of the violence and pleaded with them to stop claiming other people’s lands in the name of ancestral heritage. “Your ancestors tied you together ages ago, so do not allow greed to come between you two,” he said.

Ade, the village chief of Mere, agrees with Hamman. “I think the major problem is a lack of discipline among the youth, because both parties sat and an agreement was reached that no one should go to Garin Mallam Isah, and neither should a person attack another. The best option is to report anyone who trespasses,” the village chief said.

Hamman noted that the Garin Mallam Isa forest is vast and can benefit the whole Lafiya district and neighbouring communities if residents stick to their demarcation and stop claiming other people’s lands.

Ibrahim Yuguda, a Divisional Officer in charge of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence in the area, emphasised the security agents’ commitment towards ensuring peace in the community. Drawing more strength from ongoing collaboration with the local vigilante group known as Operation Farauta, Ibrahim assured community members of safety.

“The recent attacks and death cases have been reported to the right authorities, and investigations will soon commence,” he said.

As farming remains banned across Garin Mallam Isah, dozens who have farmlands across the area are struggling to survive, especially those who do not have an alternative source of income.

The cycle has caused Ninevah Nyala, a Lunguda indigene, to lose faith in humanity and has caused a rift in the relationship he once shared with the Wajas.

“My son’s house and mine were razed in the past, and since then, we have not recovered, because they were concrete buildings,” he told HumAngle.

Ninevah stopped farming in 2018 after discovering his guinea corn crop had been destroyed. Since then, he has relied solely on his pension as a retired civil servant.

For 65-year-old Hassan Abubakar, survival is now a gamble. He once depended entirely on farming, cultivating a piece of land that is now banned. He has charged his sons to find other trades and desist from going to the farm.

“It’s not just farming activities that come to a standstill,” Hassan said. “The schools barely function during this period. People are roaming the streets in fear and panic, and I don’t think the community will progress if these conflicts persist.”

For now, the fear in Lafiya District continues to grow.

In the Lafiya district of Adamawa State, Nigeria, violent clashes between the Lunguda and Waja tribes have escalated over a land dispute dating back to 2018. This conflict has led to numerous casualties, with civilians frequently caught in the crossfire and many displaced from their homes.

The two tribes, once harmonious, are now embroiled in a cycle of violence where retaliatory attacks and arson are common following confrontations on farmlands.

Efforts by government and traditional leaders to mediate peace have largely been unsuccessful, and unrest continues to disrupt community life, affecting farming, education, and healthcare services. Residents live in constant fear of sudden violence, significantly impacting their ability to live securely.

Despite bans on farming activities to deter conflicts, many have lost their livelihoods and are struggling to sustain themselves amidst increasing tensions.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter