Between Armed Violence And Unaffordable Healthcare

One year after he was attacked by criminals on a highway in Northwest Nigeria, Jabir Bello still has serious leg injuries, no thanks to poverty and an underdeveloped public healthcare system.

“By Allah, it is now very difficult for me to feed myself or even buy drugs,” Jabir Bello utters in a grieving voice.

The 35-year-old resident of Mana ‘Karama suburb of Sokoto city, Northwest Nigeria, is narrating his ordeal of living with a year-long torment from leg wounds caused by a highway criminal attack near the ‘Yankara community of Katsina. His condition is worsened by poverty and poor public health services in Sokoto.

He believes Nigeria’s backward security and public health systems are responsible for his predicament.

Prior to becoming a victim of the highway criminal attack which happened during the closing months of last year, Jabir was an enterprising young man. Though an indigene of Sokoto, he stayed in Lokoja, Kogi State, where he was a greengrocer. After months of business transactions in Lokoja, he usually travelled to Sokoto to visit his relatives.

The last time he travelled between the two states, on a Friday, he got trapped by a criminal gang.

Roads or traps?

Since around 2010, a form of organised crime known locally as banditry but which has now transformed into terrorism has ravaged communities in the Northwest. In addition to their initial strategies of perpetrating violence – notably, cattle rustling and raiding of communities – terrorist gangs in the region began kidnapping for ransom around 2015. Since then, highway kidnapping has been frequent.

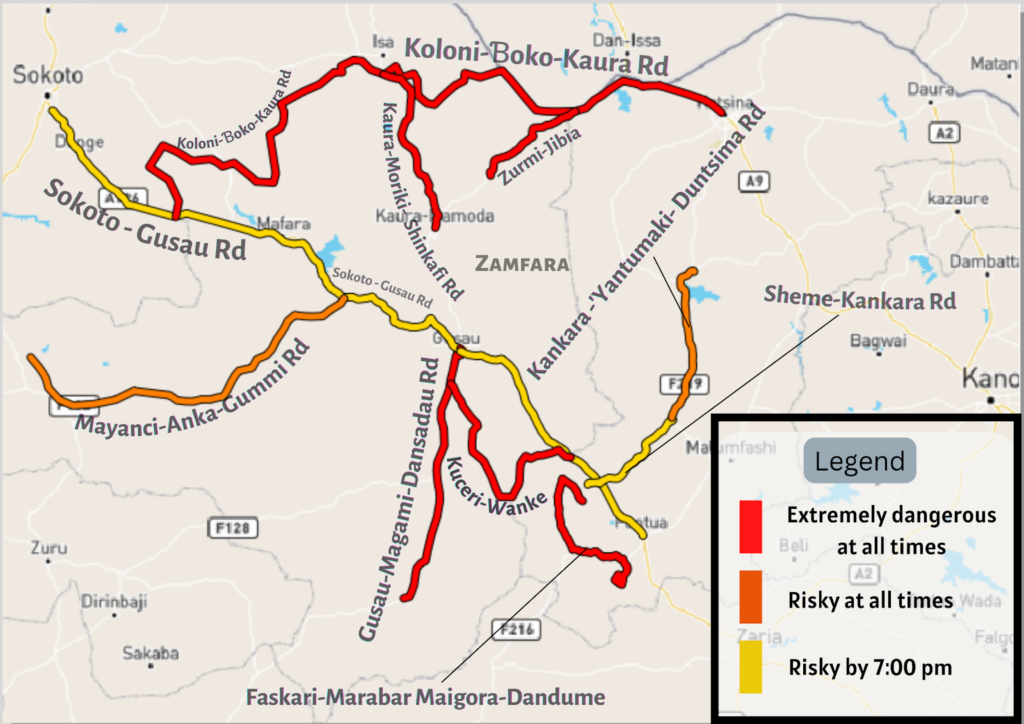

The bumpy roads linking the states and local communities in northwestern Nigeria have always consumed people’s lives in recurring fatal auto crashes. With the sustained increase in highway robbery and kidnapping, the roads are now doubly dangerous. But some roads are particularly unsafe.

Driving through routes such as the Abuja-Kaduna road, Kaduna-Birnin Gwari road, Mayanci-Anka-Gummi road, Sheme-Kankara road, and the Kankara-Yantumaki-Dutsinma road is notably risky at all times of the day. The Sokoto-Gusau, Gusau-Tsafe-Sheme-Funtua, and Kuceri-Danjibga-Keta-Wanke roads are considered significantly dangerous only after 7 p.m.

According to locals, it is “almost suicidal” to travel from Sokoto to Katsina via Colony-‘Boko-Gora-Moriki and ‘Kaura Namoda or on the Zurmi-Jibia, Jibia-Katsina, Faskari-Marabar Maigora-Dandume, and Gusau-Magami-Dansadau roads. Hundreds of people have been either killed or kidnapped on these roads.

Jabir was attacked on the Gusau-Tsafe-Sheme-Funtua road, about 500 metres from the Immigration checkpoint near ‘Yankara. “We were even stopped by the Immigration officers. We ‘settled them’ before we proceeded,” he recalls.

“As we moved steadily, our driver suddenly matched the brakes and our car stopped. An old man seated in front of me frighteningly asked the driver, ‘What is going on?’ ‘If all was fine, I wouldn’t have stopped,’ the driver retorted.” Jabir sounds dispirited as he recounts this incident.

The first person the passengers saw beside the Volkswagen Sharan vehicle carrying them was an armed local brute, about 15 years old, who fit the traditional stereotype of a ‘bandit’. “Following him was a grey-haired folk, who was obviously their leader,” says Jabir. Then, other members of the criminal group emerged from the surrounding bushes.

“In the agonising few minutes that followed, our panicky driver suddenly raced at breakneck speed. But a gunshot at our rear tire got us moving on a zigzag course through the road,” Jabir recounts. The sporadic shootings that followed saw the car crashing, leaving the driver and nine other passengers dead.

Jabir, who is the lone survivor of the attack, was shot, once in his left leg and twice in the right one. This was the beginning of his tedious journey through excruciating pain, intensified and complicated by financial inability and a fragile health system.

Unsafe roads meet poverty, poor healthcare

Following the incident, Jabir and other victims were taken to a healthcare facility in the nearby Tsafe town. The next day, his relatives were contacted. They eventually conveyed him to the Korino Hospital in Tudun Wada, Sokoto.

“They asked us to pay ₦250,000 ($575), which we didn’t have. So, we decided to take him to the Wamakko Orthopaedic Hospital,” says Jabir’s father, Bello Danfullo. Poverty is common in the Northwest. According to the United Nations (UN), 70 per cent of the region’s population lives below the poverty line.

At the Orthopaedic Hospital, Jabir’s right leg, which was fractured by gunshots, was fixed with an intramedullary rod at the sum of ₦100,000 ($230). Although Jabir was regularly taken to the hospital for follow-up treatments in the following 10 months, maggots began growing in the poorly healing leg injury, causing intense odour. “Nobody wanted to come close to me,” Jabir groans.

The deteriorating situation forced his family to take him back to the hospital and demand, against the wishes of the doctors, that the intramedullary rod be removed. Unfortunately, after that was done, Jabir fell one day and renewed the fracture on his leg.

He was rushed back to the Orthopaedic Hospital, where he was treated for a second time. “The treatment I was given is not yielding positive results. The wound is reopening by itself, showing no sign of healing,” he says.

The first of its kind in Sokoto, the Wamakko Orthopaedic Hospital is a budding healthcare facility, established less than a decade ago. It has been crucial in treating medical emergencies caused by auto crashes, criminal attacks, and other accidents. Recently, the hospital successfully conducted a knee transplant.

Operating within Nigeria’s underdeveloped public healthcare system, however, the hospital is ordinarily facing many challenges, particularly poor sanitation, insufficient personnel, inadequate working equipment, and poor funding.

Responding to HumAngle’s question on what the hospital needs to improve its services, Dr Nuraddeen Altine Aliyu, the Chief Medical Director (CMD), says: “In a case where you have severally written to the government but to no avail, you just do what you can do. We try within our capacity to treat our patients; and for orthopaedic cases that are beyond our capacity, we usually refer patients to the National Orthopaedic Hospital Dala, Kano.”

According to the CMD, complications are not always caused by poor medical expertise but by the attitude of patients.

Some patients prefer traditional medication. They only report to the hospital as a last resort when their situations are already worse. There are others who, after their discharge from the hospital, are scared away by medical bills. Hence, they refuse to comply with the hospital’s rule of follow-up health checks.

“Patients must pay first before services are rendered to them. Our services are subsidised, not free. If you see us delaying medical response, perhaps the patient has not paid their bills,” the CMD stresses.

This is the case with most other public hospitals in Nigeria. Former President of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), Professor Mike Ogirima, recently lamented that public hospitals were grossly dilapidated and underfunded. He added that the “government … withdraws some utility services like laundry, water, light, security. So each hospital is forced to source for them. This is affecting the provision of health services, training, and the general well-being of Nigerians.”

Poor funding, which forces public healthcare facilities to place high medical bills on their often poor patients, has variously intensified the suffering of such patients, including victims of conflict. In Oct. 2021, for instance, 15 victims of a criminal attack in Goronyo were in despair at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital (UDUTH) until an undisclosed person intervened by committing to pay for their feeding and medical bills.

Jabir and his family have also been impoverished and troubled by the bills. They say they have spent all their life savings. Jabir sold his motorcycle and his uncompleted building at the Gagi residential area of Sokoto to pay his medical bills. Yet, his health challenge persists, so much so that the amputation of his right leg is contemplated. The once virile, enterprising young man who had many goals is now permanently seated in one place, forced to seek public financial assistance.

Nigeria’s Northwest is not only beset with security crises, but it also has a mix of poverty and healthcare crises. Between armed violence and unaffordable healthcare are victims such as Jabir, who suffer the consequences of inadequacies in various facets of life.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter