Battling Insecurity And Pandemic, Nigeria Struggles To Keep Children In School

Having the world’s highest number of extremely poor people means millions of people in Nigeria cannot afford to send their children to school. But the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and an already deep-seated problem of insurgency has also caused those originally enrolled in school to spend months, or even years, away from the walls of a classroom.

In May, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed September 9 the International Day to Protect Education from Attack, to be celebrated for the first time in 2020. According to UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, the essence of this day is to encourage countries to ensure children “have a safe and secure environment in which to acquire knowledge and skills they need for the future”.

Globally, over 75 million children between the ages of three and 18 and living in 35 crisis-affected countries, including more than three million in Nigeria’s northeast, need urgent educational assistance.

The UN estimates that the coronavirus pandemic has led to the closure of over 90 per cent of schools worldwide. In Nigeria, this is especially the case for government schools across all levels where the facilities for online learning are not in place.

Schools in the country have been closed since March but the Federal Government has now asked administrators to “begin the process of working towards potentially reopening within this phase”.

In a statement released on Wednesday, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Nigeria, Edward Kallon, urged state governors in charge of basic education to build resilient systems that can withstand future health-related crises.

The 1949 Geneva Convention dwells patiently on the need to educate children even in situations of conflict. Among other provisions, it states that all parties to the conflict shall “facilitate the proper working of all institutions devoted to the care and education of children.”

Similar guarantees are contained in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, and so on.

Also, in May, 2015, the Safe Schools Declaration was opened for endorsement by the UN “to support the continuation of education during war, and to put in place concrete measures to deter the military use of schools”.

Though Nigeria has endorsed this declaration and has ratified all earlier mentioned international treaties, the average child in regions ravaged by insurgency still faces enormous educational challenges.

According to the UN, between 2009 when the Boko Haram terrorist group first struck and December, 2018, 611 teachers were killed in Nigeria, 910 schools were damaged or destroyed, and over 1,500 schools were forced to close.

About 4.2 million children in the Northeast are estimated to be at risk of missing out academically; and this is in a country with a general out-of-school population of 13.2 million, the highest in the world, according to a survey conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF

“The attacks on schools, communities and education itself are tragic consequences of a protracted conflict that has left a generation of children traumatised,” the international organisation said recently.

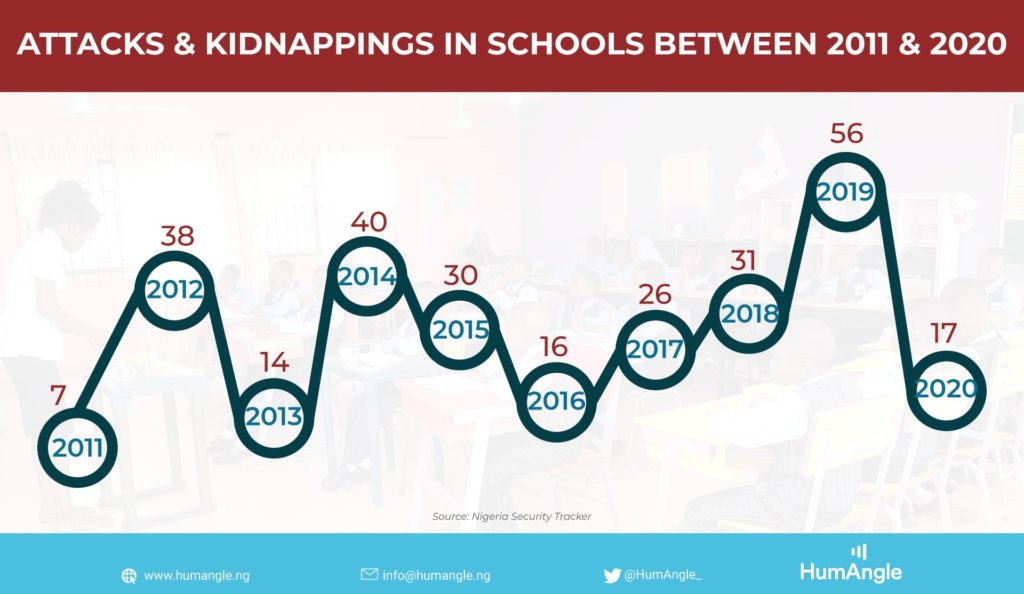

Analysis of data from the Nigeria Security Tracker by HumAngle revealed that out of a total of 9,060 violent incidents that took place between August, 2011 and August, 2020, 275 were attacks of schools. And there has been an upward trend in this since 2017, showing that even in recent years, school environments have not been respected as places of refuge as demanded by international humanitarian laws.

There were seven school-related attacks in 2011, 38 in 2012, 14 in 2013, 40 in 2014, 30 in 2015, 16 in 2016, 26 in 2017, 31 in 2018, 56 in 2019, and so far 17 in 2020. During these attacks, 1,694 civilians and 91 security operatives lost their lives while 358 people, especially school children, were victims of abduction.

Some of the most notorious incidents include the massacre of 59 boys at a boarding school in Buni Yadi, Yobe State, in 2014, the abduction of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok in the same year, and the abduction of 110 schoolgirls in Dapchi in 2018. Schoolgoing children have been affected in other attacks as well. UNICEF said in 2018 that more than 1,000 children had been kidnapped by Boko Haram members since 2013.

This sort of attacks cut across the Sahel region too. One report released by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) notes that between January and July, 2020, there have been over 85 attacks on education in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger Republic despite the closure of schools due to the pandemic.

The group added that, just as the statistics nearly indicate for Nigeria, attacks more than doubled in Burkina Faso and Niger Republic between 2018 and 2019, leading to the shutdown of over 2,000 schools. In Mali, over 1,100 schools were closed and more than 60 attacks took place in 2019 alone.

Ideological grievances held by extremist groups in the region against Western education have made attacks against schools even more frequent. But it is not only true that insecurity causes literacy rates to drop in affected communities; the lack of education has also been found to make it easier for jihadi groups to recruit foot soldiers.

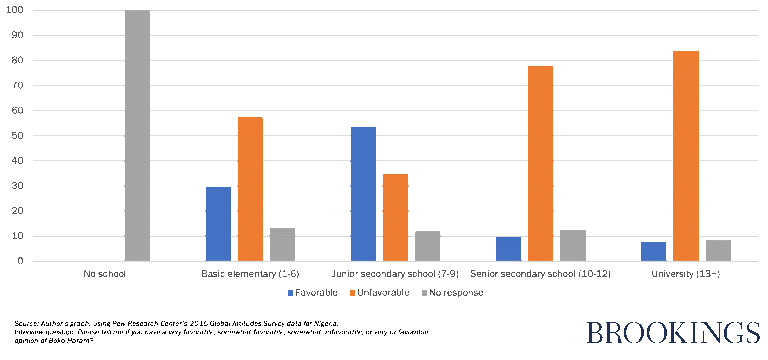

American research group, Brookings Institution, in a study published in May noted that people “with a few years of schooling beyond elementary school might be particularly vulnerable” to favouring extremist ideologies. While over 50 per cent of people with Junion Secondary School level education had a favourable opinion of Boko Haram, this dropped to below 10 per cent for secondary school and university graduates.

“Attacks on schools are a violation of humanity and basic decency. We must not allow these senseless attacks to destroy the hopes and dreams of a generation of children. We must do all in our power to ensure that schools and the children and teachers within them are protected,’’ pleaded UNICEF Executive Director, Henrietta Fore.

“As the world begins planning to re-open schools once the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, we must ensure that schools remain safe places of learning, even in countries in conflict.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter