As Borno Domesticates Nigeria’s VAPP Act, What Does It Mean For Displaced Women?

The absence of adequate laws like the VAPP Act makes the course of justice unattainable to many people. However, if significant changes are made to the Act to tone down the provisions before its domestication, it may not have the desired effect.

For women like Falmata, reportedly raped first by terrorists while in abduction, and then allegedly by soldiers of the Nigerian army at a displacement camp in Borno after she escaped, there can hardly be any talk of justice. There is no accountability for her rapists, nor compensation for her and her child conceived from the abuse.

This remains true for the thousands of women and girls who have suffered the same fate. In 2015, at the peak of the Boko Haram insurgency, with hundreds of women and girls being raped and forcefully married to insurgents, the New York Times reported that the scale of sexual violence was so rampant and systematic that “officials and relief workers described it as a deliberate strategy to dominate rural residents and possibly even create a new generation of Islamist militants in Nigeria.”

This tallies with the ideology of religious extremists who believe in procreation as a necessity towards sustaining generations of like-minded people.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that Boko Haram terrorists have raped at least 7,000 women and girls. Still, no suspected terrorist has ever been prosecuted for the offence of sexual violence in Nigeria.

The Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act of 2015 is perhaps the law most capable of ensuring absolute accountability on the sexual violence front in Nigeria, especially in the Northeast, where wartime sexual violence remains rife. The Borno state government has finally domesticated it and, if implemented well, it could be a ray of light for displaced women who face sexual violence in the state. However, HumAngle understands that certain modifications are being made to accommodate “cultural and traditional values” before full implementation.

Background of the Act

The Act is arguably one of Nigeria’s most progressive laws at the moment, for many reasons. It is a comprehensive and cohesive law operating throughout the country. This, in itself, is an important improvement, as one of the criticisms that can be leveled against Nigerian laws is its lack of uniformity: the penal code being applicable only in the north of the country, and the criminal code being applicable in the south. The VAPP Act, on the other hand, is in force in the Federal Capital Territory, but can be domesticated and implemented in any state of the federation, regardless of the region it falls under. Where there is an inconsistency between the provisions of the Act and any other law such as the penal code or the criminal code, the provision of the Act prevails.

The Act criminalises all forms of violence against all categories of people, especially the most vulnerable, while also protecting them and granting them monetary compensation.

This makes it particularly relevant to displaced women and girls in the country who remain the most vulnerable to sexual violence in Borno state due to the insurgency and the resultant displacement and economic disempowerment they suffer.

The Act is also the first and only Nigerian law that recognises that men can be raped. It does this by broadening the definition of rape, and the conditions through which penetration can occur. Under previously enacted laws, vaginal penetration of the victim remains a key ingredient of rape that must be proven before a valid conviction can take place. This automatically sidelines male victims.

Further, the Act recognises and criminalises even economic violence, which usually has displaced women in its centre through the economic disempowerment they usually have to go through.

It also criminalises female genital mutilation.

Domestication

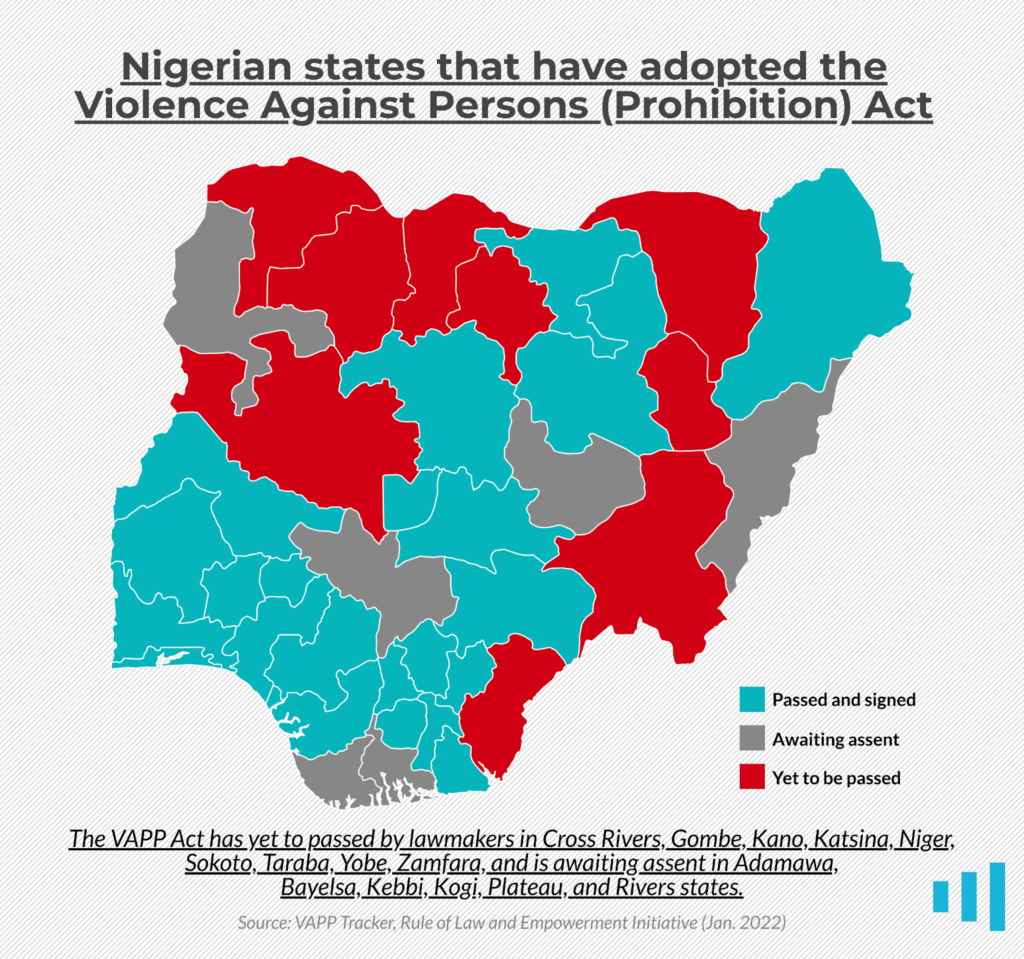

Still, only a handful of states in Nigeria have domesticated this Act. Many states remain reluctant to, mainly due to cultural and traditional beliefs which they insist negate some parts of the Act, including, perhaps, the prohibition of female genital mutilation, domestic violence, forced marriage, and harmful traditional practices such as widowhood practices that harm women.

Flier showing domestication rate of the VAPP Act. Illustration credit: ‘Kunle Adebajo/HumAngle

Activists all over the country have consistently pushed for its domestication due to its numerous advantages and what it could mean for the prospects of justice for victims of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV).

A prominent body that has gone as far as conducting peaceful protests and rallies across northern states to push for the domestication of the Act is the NorthNormal group, a gathering of young women from northern Nigeria committed to raising awareness on SGBV.

Fakhrriyyah Hashim, co-founder of the advocacy group, said in an interview that NorthNormal has two objectives: pushing for “the domestication of the Violence against Persons Prohibition Act (VAPP), and championing the conversation on various forms of gender-based violence and rape culture across northern Nigeria.”

HumAngle understands that during one of the group’s rallies held in Nov. 2019 in Niger State, protesters were told at the State House of Assembly premises by members of the house that the state would have to first reconcile some of its cultural beliefs with the provisions of the Act so as to smoothen compliance from the people when it is eventually domesticated.

This reinforces suspicions that there is a deliberate reluctance rooted in perceived incompatibility between culture and the Act’s provisions.

Borno government approves the Act

On Monday, Jan. 10, 2022, Borno state governor, Prof. Babagana Umara Zulum, signed the Act into law in his state. Still, it was not without making reference to the people’s values. He was reported to have said that the Act had been domesticated “with the needed amendment to tally with culture, norms, and tradition of the people of the state.”

Borno, which has been most affected by the ongoing Boko Haram insurgency, has experienced an alarming increase in cases of SGBV on internally displaced persons perpetrated by people on all sides of the divide: terrorists, humanitarian workers, and even camp officials.

HumAngle recently reported that a humanitarian worker identified as Huzaif Abdurrauf raped a 14-year-old girl in Maiduguri, Borno state capital. He had lured her into his house by inviting her to do his laundry, as she, like many young girls around, usually did menial jobs.

There, he raped her. The girl reportedly committed suicide afterwards.

HumAngle has also reported the sex-for-food menace across IDP camps in Borno State, where vulnerable women were being made to have sex in exchange for food, while also being abused by security personnel, including soldiers and members of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF). The report found that the sexual exploitation had been so internalised among the women IDPs that they regarded it as an unavoidable aspect of their lives.

“At the IDP camps, what we have is not a growing case of rape but a growing case of consent and less and less sex without consent,” one of the women said. “It has become normal. If you are a lady, you cooperate and get what you want much more easily.” This exploitation is a form of sexual violence that can be addressed through the provision against economic violence in the VAPP Act.

In 2017, The Crisis Group released a report in which it laid out procedures that may facilitate the Nigerian government’s prosecution of terrorists, specifically for the offence of sexual violence. There are also many laws that already protect women to some extent. But the criminal justice system has often failed to act.

While it remains true that women and girls are reluctant to report sexual abuses suffered, it is still not the case that instances have not been reported at all. Sexual violence is weaponised both in wartime and in the aftermath of war, on women and girls, in Borno. Violations are committed by state and non-state actors, with victims continuing to speak up about them. Still, Suspects are occasionally imprisoned and sometimes prosecuted for terror attacks, but never for the offence of sexual violence.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, reported cases of numerous forms of sexual violence carried out by Boko Haram, including forced marriages, rape, sexual slavery, and other incidents of sexual violence in northeast Nigeria went from 644 in 2016 to 997 in 2017. Doubtless, there are many more unreported. Leadership, a local newspaper, also reported in March 2020 that “rape cases constitute 90 per cent of criminal cases handled by various courts in Borno state in the last two years.”

The absence of adequate laws like the VAPP Act means that prosecution and justice become increasingly complicated and even unattainable. The resultant lack of accountability promotes more cases of sexual violence. However, if significant changes are made to the Act to reduce punishments either directly or impliedly, or certain sections removed before domestication, it may fail to achieve the revolutionary results it was intended for.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter