An Illicit Gold Economy is Pushing Desperate Nigerians into Southern Algeria

For many young people in Nigeria’s Borno State, the journey to Algeria was meant to be an exit from violence, but it has become another entry point into a regional war economy where gold pays for guns, and desperation becomes strategy.

Whenever Abdul Mahmud speaks about the journey from Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, to southern Algeria, in North Africa, his voice carries a sense of loss and desperation. His handlers in Algeria promised him survival and hope, but both came wrapped in danger.

Abdul learned to dig vigorously and endure gruelling conditions in Algeria’s illicit gold fields, where there was no one to protect him. He met men like him, young and desperate, scraping gold from the earth while their own lives hovered at the edge of collapse.

“You don’t think of tomorrow,” he says. “You think of today, and whether today will end.”

Back in Maiduguri, the capital city of Borno State, Bakura Ashemi smiles as he tells his own version of the story. He is in his twenties and counts himself among the few lucky ones. Six months in Algeria gave him what years in Maiduguri could not: a foothold.

“Alhamdulillah, I bought a piece of land for ₦4 million,” he brags, pride flickering across his face. He is already building, hoping to raise the walls to lintel level. Before migrating to Algeria, his family of nine survived on his father’s ₦30,000 monthly pension, which barely lasted for the first 10 days of the month. To support his family, Bakura worked as a labourer at construction sites, but the high cost of building eliminated those jobs before he left for Algeria.

For many young men in Nigeria’s northern region, survival has become a long journey that starts with unemployment at home and extends deep into the desert, across the Sahel, and all the way to southern Algeria. The economic devastation caused by years of Boko Haram insurgency has led dozens of youths in Maiduguri to travel to gold-mining settlements across the Niger Republic and Algeria to chase quick wealth.

Life as miners, however, leads them straight into the grip of armed groups entrenched in the Algeria-Mali-Niger borderlands. Mallam Ali, a real estate agent in Maiduguri, said in the past months, over a dozen young men who returned from Algeria have bought houses.

“You can count dozens of youths from Gwange, London Ciki, Custom Area, Ruwan Zafi, Kaleri, Dikwa, Low-cost Housing areas of Maiduguri and a lot of others that have either been to Algeria or are living there currently,” he noted.

What begins as an escape from insurgency increasingly circles back under a different flag. “There are a lot of jobs you can do there that can fetch you thousands of naira equivalent per week,” said Abdu, one of the miners who recently returned from Algeria. “I used to sell snacks in the daytime, and at night, we load trucks for smugglers across the Algerian-Malian borders.”

He revealed that some Nigerian migrants choose to work for the armed groups for faster money, fighting against rival factions and state forces.

Like Abdu, another young man in his mid-20s from Maiduguri, simply identified as Usman, has found solace in the gold rush in southern Algeria. Since he finished secondary school three years ago, he has been unemployed. With no funds to continue his education and no job opportunities available, he accepted ₦100,000 from a friend already working in the goldfields to move to Algeria.

“I had no choice,” he said during a phone call from one of the mining settlements in the country. “There was nothing for me in Maiduguri.”

Usman is one of hundreds of young men pushed by economic hardship and insurgency to exploit the cross-border illicit gold economy. According to the 2025 State of the Nigerian Youth Report, 80 million Nigerian youths are unemployed. In Borno, where armed violence has devastated livelihoods, unemployment serves as both an economic statistic and a recruitment pool.

HumAngle spoke to Nigerian migrants caught up in the goldfields of southern Algeria, seeking better economic opportunities. In separate interviews, many stressed that the illicit gold economy in Algeria remains tempting, particularly given the lack of economic prosperity at home.

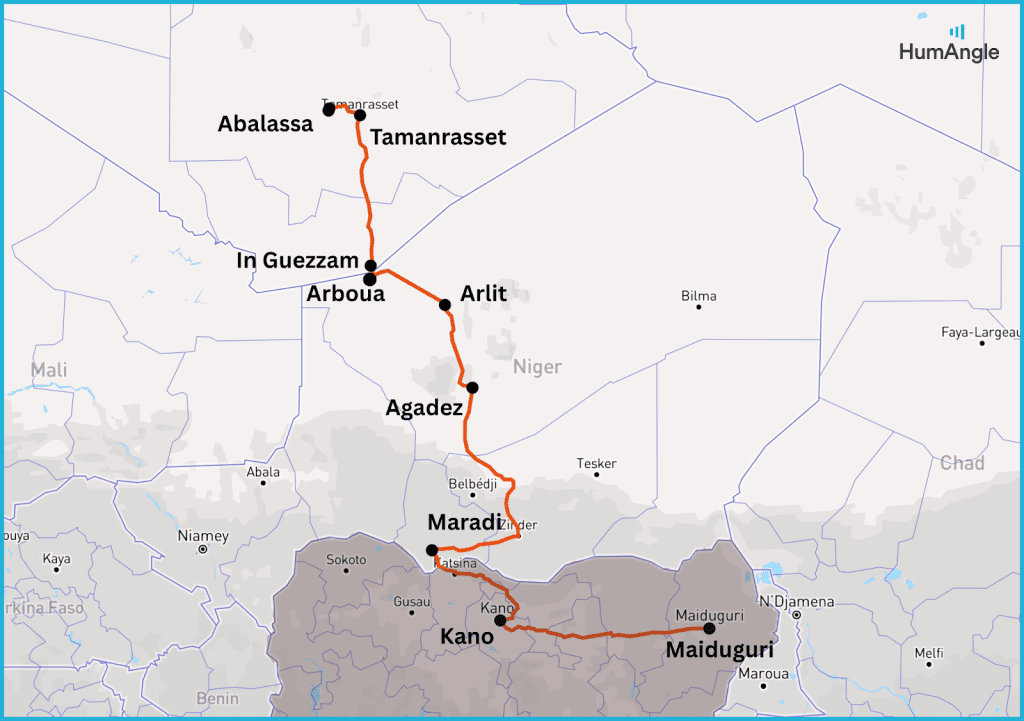

The journey from Maiduguri is both perilous and demanding. Migrants head from Borno to Kano, then cross the border into Maradi, in the Niger Republic, embarking on a three-day journey across the Sahel to southern Algeria.

“At Maradi, everyone buys water in jerrycans,” Usman said. “If the vehicle breaks down and your water runs out, you can die. Along the way, you see decomposed bodies and skeletons, people whose cars broke down and who never made it. Some unlucky travellers have encountered robbers who stripped them of their valuables.”

‘The special capture zone’

Sources told HumAngle that many people have gone missing or lost their lives while crossing to Algeria in search of greener pastures. In their pursuit of quick gold wealth in Algeria, they pass through Agadez before reaching Arboua, an Algerian border town that has become a transit hub for young men from Nigeria, Niger, Mali, and beyond. Other migrants proceed to Abalassa, another settlement for gold miners in Algeria.

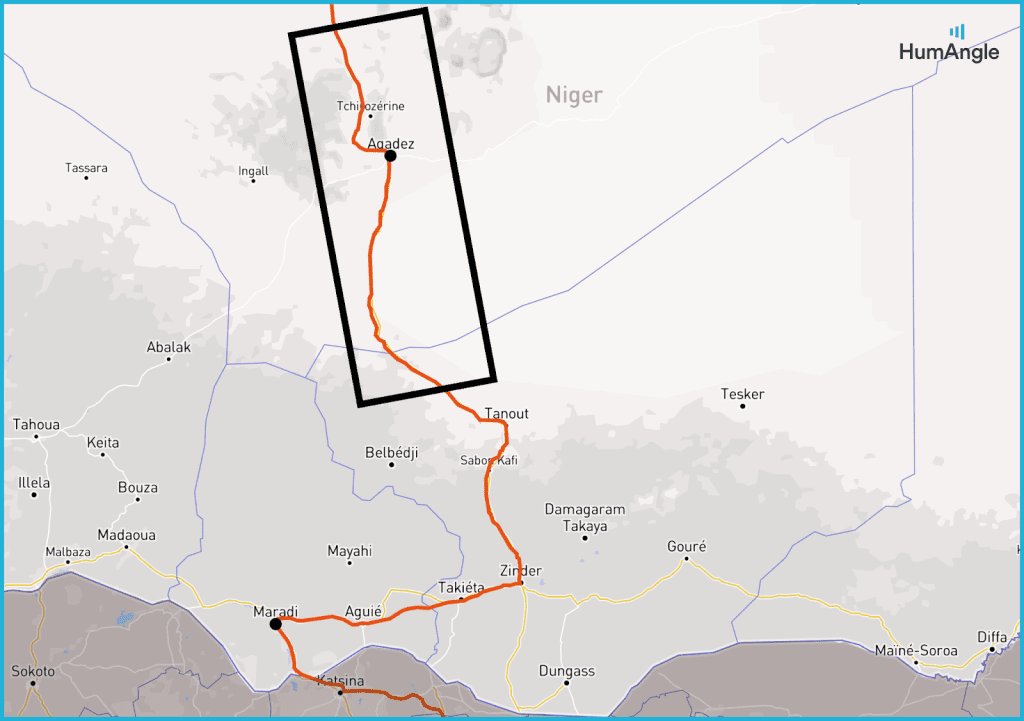

Those HumAngle interviewed said they experience dramatic shifts as they move north of the Zinder–Maradi axis. Beyond this point, their journey becomes a solitary line of survival along hundreds of kilometres of the Trans-Saharan Highway.

A satellite analysis shows that this highway is the only continuous infrastructure traversing an otherwise desolate landscape. There are no significant parallel routes, no rest stops, and very few permanent settlements along the way.

The stretch forms what could be considered a “spatial capture zone”. It’s a no man’s land extending roughly from Maradi through Agadez and toward southern Algeria. Satellite imagery analysis shows long gaps between settlements, often spanning 30 minutes at a moderate speed, with no visible water access points or emergency infrastructure. The landscape offers very limited alternatives: nowhere to divert, nowhere to wait, and nowhere to recover.

HumAngle’s satellite analysis further reveals that, after Agadez, the spatial pattern shifts to informal tracks branching off the highway. Temporary encampments appear along the route, marking a semi-governed zone that overlaps with the operational geography of transborder armed networks. These informal routes serve as access roads to strategic points along the highway, with non-state armed groups appearing to have taken control of the area. Here, movement is controlled to manage access and ensure survival against the harsh forces of the landscape.

Approaching the town of In Guezzam and the Arboua–Abalassa axis in Algeria, the road feeds directly into the extraction zones, where satellite imagery shows artisanal mining sites pressing against the edges of settlements. Around Arboua, mining encroaches on the northern fringe of the locality, with excavation along the western edges of In Guezzam, and less than five kilometres from residential clusters. In Abalassa, locals have to travel a similar five kilometres to the mines near the hills.

West of Arboua, a series of mining sites is arranged in parallel, including Tin Zahouten. These sites exhibit a consistent pattern of dense artisanal mining pits, informal access roads connecting to nearby towns, and camps likely established to regulate movement. The pattern indicates an organised extractive economy across the region.

An inspection of time-series imagery from the past five years reveals a gradual encroachment of mining activities. Initially, pits appear at a distance, but as access routes multiply, they advance closer to the core of settlements. Towns are increasingly serving as logistical hubs for mining operations, particularly those associated with armed groups, while showing little evidence of broader socio-economic development. The growth of infrastructure seems focused on facilitating further extraction rather than improving community welfare.

The satellite evidence collectively shows that migrants’ journeys directly lead to the mines. The same routes that expose them to harsh environmental conditions also bring them into communities that are already entrenched in extraction economies, often governed by armed groups. Viewed from above, these towns appear as interconnected nodes within a system where distance, isolation, mining, and violence mutually reinforce one another. For these travellers, the path is seemingly inevitable.

Geopolitical changes have made travel more difficult. Goni, an environmental health officer in Maiduguri, noted that after Niger’s July 2023 military coup, travel became more dangerous and fares increased significantly. He said the cost of travelling for his younger brother amounted to hundreds of thousands of naira.

“When Niger was still in ECOWAS, a national ID card was enough,” he said. “Now immigration demands passports and visas. Drivers bribe officials or move at night to avoid checkpoints.”

Travelling to Algeria costs between ₦250,000 and ₦300,000, and funds are often raised by selling family assets. “Parents sell land, livestock, anything,” he added. “People believe gold will change everything.”

The recruitment trap

The stories of migrants returning home with millions of naira after the illicit gold mining endeavours fuel the migration pipeline. But the reality on the ground is more complicated and far darker.

Abba, a Maiduguri native who has spent over two years in the Algerian goldfields, described a world where mining, crime, and armed violence blend into one economy.

“The goldfields are owned by armed Arabs and Buzu groups,” Abba said. “They recruit labourers through agents. Payment is either cash or one-third of the proceeds after weeks of work.”

Sources told HumAngle that owners of these mining sites are heavily armed, using dangerous assault weapons to defend themselves against rival groups, and sometimes Algerian security forces.

“If you try to steal gold,” he added, “they will kill you instantly. The least punishment for stealing is amputation. There is a guy whose hand was amputated for stealing gold that comes around here.”

More quietly, recruitment into armed groups happens alongside mining. It is rarely open in towns like Arboua, but it thrives in criminal zones such as Bakin Rai, where idle youths are easy targets. In Arlit, a border town in the Niger Republic that attracts migrants, the recruitment drive is active, with gun trucks and heavy weapons displayed.

“They offer fast money,” Abba confessed. “Much faster than mining.”

Abu Mamman, who recently returned from Algeria, was blunt when he spoke to HumAngle.

“In Arlit, there’s no real difference between mine owners, rebels, and terrorists,” he said. “Some armed groups control mining fields. Others recruit fighters. Many do both. I have served as their driver but did not carry any gun.”

According to him, foot soldiers can earn close to ₦1 million per operation, sometimes making several millions in a short period – sums that would take years to earn legally.

“These groups also operate as mercenaries,” he said. “They fight jihadist factions like ISWAP and Ansaru, or rebel groups fighting Sahelian governments. Some even clashed with Wagner mercenaries along the Mali border last year.”

The gold-fuelled insurgency

What these migrants encounter on the ground mirrors broader regional trends. The Centre for Preventive Action, through the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), warned in a report that the increasing strength of violent extremist organisations in the Sahel poses a significant threat of a damning humanitarian crisis.

The report highlights how the collapse of international counterterrorism support and weak regional leadership have created a vacuum exploited by groups of terrorist organisations alongside non-state actors like the Wagner Group.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the Sahel produced an estimated 228 tons of gold in 2021, worth over $12.6 billion. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining accounts for nearly half of that output, employing over 1.8 million people – mostly informally and without regulation.

Armed groups exploit this informality by taxing mining sites, controlling labour, and smuggling gold across porous borders to international markets. The same desperation that drives youths from Maiduguri into the desert also fuels Sahelian insurgencies.

A circle closing on itself

Back in Maiduguri, Alhaji Yerima says the signs are now apparent.

“Anyone who comes back from Algeria quickly with big money either joined an armed group or stole gold. Mining alone doesn’t make you rich that fast,” he declared.

For many young Nigerians, the journey to Algeria was meant to be an exit from violence, but it has become another entry point into a regional war economy where gold pays for guns, and desperation becomes strategy.

Unless local livelihoods are restored and effective mechanisms are established to remove gold production from armed group control, migration routes from Maiduguri through the Sahel to southern Algeria are likely to remain closely linked to insurgent networks, with the associated security risks extending beyond their original areas of origin.

The proliferation of informal migrant settlements along the transboundary mining sites poses a far greater danger of solidifying breeding grounds for criminals and terrorists. Migrants like Abu Mamman have said that “some of the armed groups exchange visits, provide safe haven and provide personnel assistance to each other across the Sahel region”.

Additional reporting by Mansir Muhammed.

Young men from northeastern Nigeria are driven by poverty and Boko Haram insurgency to perilous journeys, seeking fortune in Algeria's illicit gold mines. In these mines, dominated by armed groups, they endure harsh conditions and face recruitment into criminal networks for quicker financial gain.

Traveling through treacherous routes in the Sahel, migrants encounter severe risks, including environmental extremes and violent confrontations.

The gold economy in the Sahel, largely unregulated and exploited by armed factions, fuels regional insurgencies, as migrants become trapped in a cycle of violence and economic desperation. The allure of becoming wealthy overnight often ends in entrenchment within a war economy where gold funds arms trading.

Unless local economic conditions improve and control is reclaimed from militant forces, these migratory paths will persist, cementing connections between mining and militancy in the region.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter