After Years of Arbitrary Military Detention, Two Young Nigerians Rebuild Their Lives

Giwa Barracks was the place that shaped Saleh and Muktari’s thirst for knowledge. After enduring unimaginable hardships there, both men turned to education to reclaim their futures and build new lives.

Saleh Hassan tilted his head upwards occasionally, his gaze fixed on the night sky as he fought back tears. His eyes glistened as he recounted his ordeal in detention at Giwa Barracks in Maiduguri, Borno State, northeastern Nigeria. He paused, determined not to let the tears fall, but his voice faltered as he began his story.

“It was 12 years ago,” he said.

The night it began

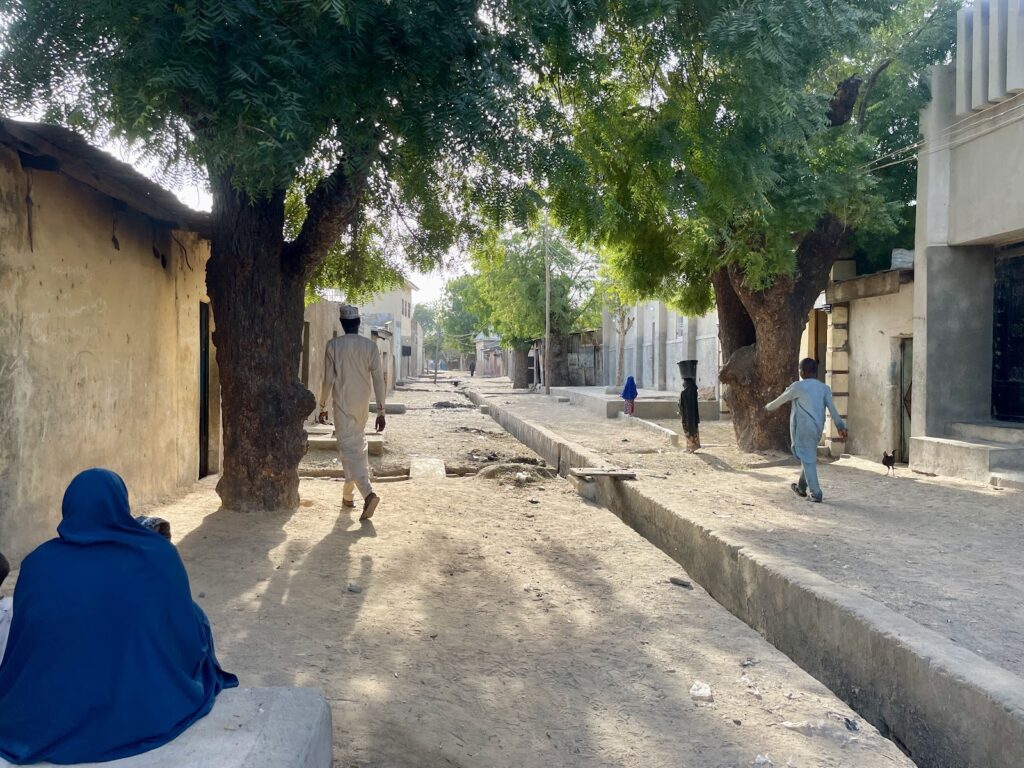

A heavy silence blanketed Mafoni ward, a community in the centre of Maiduguri, on Dec. 6, 2012. For Saleh, that night marked the start of an ordeal that would reshape his life, leaving scars both visible and hidden.

The faint echoes of distant minarets calling Muslims to early morning prayer barely pierced the stillness. Yet something felt off. The nearby mosques didn’t call for prayer that night.

At the time, Saleh was 17, and his friend Muktari Mohammad was 18. They moved cautiously through the quiet streets, their instincts tingling with unease. The night was far too quiet as if the world was holding its breath. They had only taken a few steps towards the nearby mosque when a boy from their street came running towards them, his voice urgent and breathless.

“Sojaa! sojaa! [soldiers, soldiers] Hide! The soldiers are here. They’ve surrounded the area!” the boy warned, his eyes wide with fear.

In that moment, Saleh’s heart sank. He regretted his decision to spend the night at home in Mafoni. Like many other boys in the community, he usually stayed overnight in other neighbourhoods where the threat of arrest was less imminent, returning during the day. The soldiers saw every boy as a suspect.

Communities where the boys had not joined Boko Haram lived without the constant fear of arrests, unlike those areas where young boys, some barely in their teens, carried out attacks.

At that time, Boko Haram was waging a campaign of terror to establish an Islamic State. They attacked communities, destroyed government facilities such as schools and police stations, and targeted military and police checkpoints. After such attacks, they would retreat into nearby communities, leaving residents too afraid to speak out for fear of reprisal. In response, soldiers frequently conducted arbitrary arrests, profiling and rounding up young men and boys.

That night, Saleh had sought comfort in his home. But now, he and his friend found themselves racing across the street, seeking refuge in a mosque. They crouched among the worshippers who had just finished vigil.

Everyone knew what was coming. They had heard it happen before. The silence in the mosque was suffocating, the air thick with fear and heavy with unspoken prayers.

Then, the silence was shattered. The mosque’s doors burst open with a force that shook the ground beneath them. A soldier, his face covered, stormed in.

“Out! Everybody out!” he shouted, kicking at those who hesitated.

The boys scrambled to their feet, their hearts pounding as they were herded into a single file, their clothes tied from behind to the next person.

They were marched through the dark streets until they reached an open field that served as the community’s dumping ground. The stench of decay clung to their nostrils, mingling with the fear radiating from the boys.

Saleh glanced around, his eyes widening at the sight of military pickups and armoured trucks, their ominous forms barely visible in the predawn light. The field was already filled with other boys lying face down on the ground, soldiers standing over them with sticks, striking at any sign of defiance. More boys were being marched into the field, escorted in single files by soldiers; their heads bowed under the weight of fear and uncertainty.

Marked a suspect

The systemic issues underlying the military’s actions were deeply rooted in a broader, desperate strategy to counter the escalating insurgency. Yet, these measures often ignored due process, leading to widespread abuse and arbitrary arrests. Such actions fostered fear and distrust between the local populace and the authorities, complicating efforts to address the insurgency at its roots.

“Lie down!” the soldiers barked, and Saleh and the others quickly complied, pressing his face to the ground. Saleh prayed, hoped, and wished.

He had heard stories about the military’s so-called ‘computer’, a device purportedly capable of identifying Boko Haram members with a single glance. Saleh clung to the hope that this screening would prove his innocence.

They lay on the ground for two hours, their bodies stiff and aching, until the morning sun started burning through their skin. Finally, the boys were ordered to their feet and lined up in front of an armoured tank. Inside the Humvee, the silhouette of a man wearing a balaclava gestured decisively with his hand—left for a suspect, right for release. The “computer” was no advanced machine but a man, who silently determined their fates with a wave.

Each movement sealed a boy’s fate, based solely on an inexplicable instinct as to who was Boko Haram and who was not. This process, devoid of logic or evidence, left Saleh and others at the mercy of an unseen judge.

“The first round of screening identified only eight boys as suspects. We were all relieved,” Saleh recalled.

But that relief was short-lived. A military pickup van with tinted windows rolled into the field. The soldiers conferred in hushed tones, their faces grim, before returning to the boys. The screening process began again. This time, there was no pretence of deliberation. One by one, each boy was waved to the left.

“Now you are all suspects,” the soldiers announced.

Saleh’s heart plummeted as he joined the swelling group of ‘suspects,’ his fate seemingly sealed by an arbitrary process he couldn’t comprehend. The group grew to 62, leaving only two spared: an elderly man and a boy who identified his father as a policeman.

“We were all loaded onto military pickups,” Saleh recounted. “Crammed into the back like livestock, our bodies were pressed together, limbs tangled and twisted at odd angles, like we were logs of wood or bundles of goods being transported. The lack of space made breathing difficult, and every movement caused discomfort as elbows jabbed into ribs and knees dug into backs.”

Every sharp turn jolted their battered bodies, the discomfort compounding with every passing moment. After what felt like an eternity, the truck abruptly stopped.

As they were herded out of the vehicle, his eyes immediately latched onto a rusted sign swaying on a barbed wire fence. “RESTRICTED AREA,” it read.

“The words seemed to scream at us,” Saleh said.

Now at Giwa Barracks

Dragged from the truck, the boys were thrust into a nightmare. Some were chained to trees, others handcuffed and isolated, while the rest were forced to lie face down under the relentless sun. By evening, they were given polythene bags containing their first meal of the day, which tasted like ash in Saleh’s mouth.

“We were then herded into the holding cell. The sight that greeted me was horrifying,” Muktari narrated. “The cell was a long, hollow hall, crammed with hundreds of boys like me, their bodies emaciated, skin stretched thin over protruding bones.”

Inside, the air was thick with the unbearable stench of sweat, faeces, and fear. Each breath felt like inhaling despair.

“Lying down was a luxury. We could only stretch our legs by taking turns, but eventually, even that became impossible as our numbers overwhelmed the space,” Saleh said.

Days turned into weeks. The cell became a living hell, with only two brief outings a day to collect food and relieve themselves.

“The heat was suffocating; we were always pressed together. Breathing was hard, hunger gnawed at our stomachs, thirst burned our throats, and every day people died,” he recounted. “When someone died, we fought to remove the body so we could stretch out, drink water, or relieve ourselves.”

Saleh’s voice faltered as he spoke of those who ran mad, their minds broken by the unrelenting torment. “They would thrash about the cell like rag dolls until they finally lay still,” he said. “Nobody wanted to be locked inside that place. The less clothing you had, the more comfortable you were from lice bites. Everyone was bare-naked, wearing only boxers. Any additional clothing meant breeding lice.”

Saleh wished he was imprisoned for life in a regular prison rather than being at the detention cells in Giwa Barracks.

After four months and two weeks, five of them were released. Saleh was among the fortunate few, but the others, including Muktari, hoped to be released in due course—hopes that were never realised.

Saleh’s ordeal ended with his release, but the experience left an indelible mark.

Muktari’s escape

The perception of the military as protectors was increasingly eroded, especially as communities bore the dual horrors of the insurgent brutality and the military’s heavy-handed counter-insurgency tactics.

Muktari was still inside the Giwa Barracks military detention facility when Boko Haram launched a devastating attack on March 14, 2014, a raid that left the city in ruins and claimed countless lives. The air was alive with chaos—the relentless rattle of gunfire mingled with the anguished cries of the wounded and dying. Thick black smoke spiralled into the sky, transforming the military base into a battlefield.

It was during this attack, a year after his detention began, that Muktari managed to escape. He had heard chilling stories about the underground cells—grim chambers where high-risk Boko Haram detainees were held. Fortunately, Muktari had been transferred to a regular cell after being deemed unaffiliated with the insurgents.

As Boko Haram stormed the barracks, they executed a calculated raid. They shattered cell doors, freed their members, and extended an ultimatum to others: follow them for safety or remain behind to face the wrath of the soldiers. The insurgents warned those choosing freedom that the “kafirs” (soldiers) would likely kill them.

Many detainees, driven by fear of reimprisonment, joined the insurgents. Muktari described the exodus that day—some departed and never returned, while others became absorbed into Boko Haram. Over time, a few of those who initially followed the insurgents returned through the government’s repentance programme, seeking to reintegrate into society.

Among those who returned from the government repentance programme was a boy from Mafoni, now a man. During his time with Boko Haram, he had risen to the rank of Amir (commander), taking four wives and fathering many children. Eight years after being taken, he returned home under the repentance programme, revealing that he had lacked any means of escape while in the bush.

Life after Giwa Barracks

When Saleh was arrested, he had already dropped out of school after completing primary education. As a teenager, he was focused on earning a living, joining his friends as an “okada” [motorbike taxi] rider.

However, “After Giwa Barracks, I came out with a passion for school and regrets for dropping out earlier,” he told HumAngle.

Determined to reclaim his abandoned education, he enrolled in an adult literacy school. His passion for education continued to grow. This decision began a journey that reignited his love for learning.

Following the completion of the literacy programme, Saleh’s ambition grew. He enrolled in a formal secondary school, determined to carve a new path for himself.

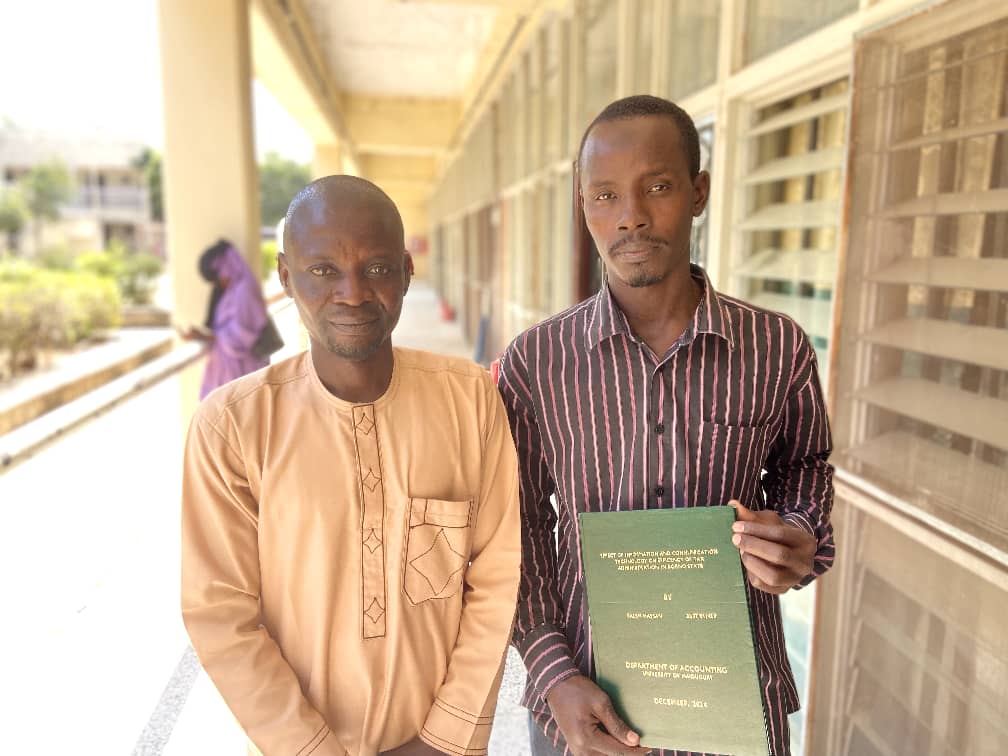

He later gained admission to the university after completing a diploma in accounting at Ramat Polytechnic in Maiduguri. “I’m not stopping anytime soon; I want to pursue my master’s degree, too,” Saleh said.

Muktari, on the other hand, had never attended school before his arrest. Reflecting on his life, he said, “Had I been going to school, I would not have been taken away.”

During these arbitrary arrests, soldiers often assumed that boys who were not in school were more likely to be Boko Haram suspects. This assumption deeply affected Saleh and Muktari’s sense of identity and self-worth during their detention at Giwa Barracks. The harsh conditions they endured became a turning point, strengthening their resolve to reject the label imposed on them.

When Muktari left Giwa Barracks, he saw his release as a chance to rewrite his story. Like Saleh, he enrolled in an adult literacy programme, determined to make up for lost time. His persistence paid off when he gained admission to Ramat Polytechnic, where he studied civil engineering and graduated in 2024.

Saleh, on the other hand, graduated from university with a second-class upper degree in accounting the same year. He told HumAngle that he had aimed to graduate with a first-class degree, but balancing the demands of managing a shop while attending school was challenging.

For Saleh, education became a beacon of hope. Reflecting on his journey, he said, “Education gave me hope and a reason to move forward. It’s not just about getting a certificate, but about realising that I can contribute positively to society.”

“No matter how far you think you’ve gone, it’s never too late to turn back and start again,” he added.

Now, at 29 and 30, Saleh and Muktari focus on running the provision store they jointly manage.

Saleh Hassan and Muktari Mohammad, two young men from Maiduguri, Nigeria, recount their harrowing detention experiences at Giwa Barracks amid the Boko Haram insurgency.

Arrested during arbitrary military operations targeting young males suspected of insurgency ties, they endured months of inhumane conditions. Saleh was eventually released, embracing education to reshape his life, furthering his studies in accounting and promoting societal contributions.

Muktari, who escaped during a Boko Haram raid, also turned to education, studying civil engineering. Both now manage a provision store, using their experiences to fuel personal and communal growth.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter